Site navigation

Archived

You are in an archived section of the website. This information may not be current.

This page was first created in December, 2012

Collaborative Indigenous Policy Development

IQPC 6th Annual Conference

Is economic development possible on Indigenous land?

Fabienne Balsamo on behalf of Tom Calma Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner,

Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission

2 May 2007

INTRODUCTION

Thank you for the opportunity to speak here this morning. I would like to begin by acknowledging the traditional owners, the Turrbal people on whose land we are on today.

I work in the Native Title Section of the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission. Over the past 12 months, this section has supported the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner in his research into the opportunities and the challenges for economic development on Indigenous land. In 2006 the Commissioner conducted a national survey of traditional owners to find out their views about economic development on their lands. He also analysed the Australian Government’s policies and commitments to economic development on Indigenous land. The content of this paper is a summary of this research.

There is no doubt that sustainable economic development is essential for the well-being of Indigenous communities on Indigenous land. This is not just my view; this is the view of the majority of Indigenous people and traditional owners who responded to a national survey conducted in 2006 by the Human Rights Commission. 1 It is also the view of the Australian Government. Over the past 12 months, the Government has undertaken an ambitious economic reform agenda that is designed to stimulate economic activity on Indigenous owned land. In fact, there is now widespread agreement that action is required to assist the many remote, Indigenous families who languish in overcrowded accommodation in communities where there is minimal employment, and little action to prepare the next generations for the future.

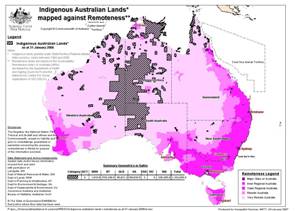

Before I go any further I need to explain what I mean by Indigenous land. Land that has been returned to Indigenous people through land rights or through native title over the past 40 years now covers just under 20 percent of Australia’s land mass. 8.5 percent of the Australian continent is under native title and 14.4 percent is land that has been returned under land rights statutes. Some of this Indigenous land overlaps. With one or two exceptions, all of this land is located in the most remote areas of Australia. Let’s look at the location of land rights land against a shading of remoteness. The definition of remoteness is determined by the Accessibility Remote Index of Australia (ARIA); the most widely used classification of remoteness.2

Land Rights

SLIDE 1

INDIGENOUS LAND UNDER STATUTE

(Click on map for expanded view)

What you are looking at here is land under land rights regimes; in other words, land that has been returned to Indigenous people by acts of parliament. While there are different land rights acts in each of the different states and territories, in the main, these statutes give the traditional owners freehold possession of the land; that is, the same rights to title as any Australian may have to land purchased under the Torrens system.

The palest pink area of the map demonstrates the region where Australia is defined as very remote. As you can see, this is where the vast majority of land rights land is located. The land is remote on a number of levels. It is distant from major cities, it is generally not serviced by roads or by other utilities like electricity or mains water, and it has limited if any infrastructure. The map shows us that land under statutory land rights is overwhelmingly represented in the central desert regions of Australia across Western Australia, the Northern Territory and South Australia. There are also tracts of land in the remote north of the Northern Territory, in the coastal regions of Western Australia’s northern belt and the coastal Cape York areas of Northern Queensland

Some of the land in New South Wales and to some extent in Queensland provides an exception to the trend for land to be remote and marginal. While the land granted to land councils in NSW is in many small parcels rather than large areas of country, some of it is very valuable in terms of its potential for development, both residential and commercial.3

Native Title

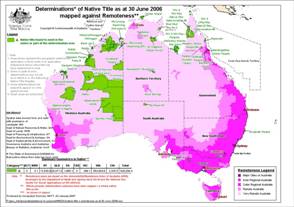

SLIDE 2

LAND UNDER NATIVE TITLE

(Click on map for expanded view)

Across Australia, just over 96 percent of all native title land is classified as very remote.

- In terms of the size, Western Australia has by far the largest areas of native title land of any Australian jurisdiction. Ninety two percent of the area of native title determinations is in Western Australia (WA). A large proportion of native title land in WA is in the Gibson, Tanami and Great Sandy Desert regions as well as in the Kimberley. In the other states and territories native title rights and interests have been recognised over smaller parcels of land. You are also no doubt aware that a 2006 determination found that the Noongar people have traditional interests and rights to land in the Perth region. This is an area classified as ‘urban’ by ARIA. However this determination is under appeal by both the WA and the Australian Governments.

- In Queensland is in the ‘very remote’ Cape York region and in the Torres Strait.

- In South Australia it is in the ‘very remote’ north central region of the state which is partially located within desert regions.

- In the Northern Territory it is in ‘very remote’ regions and native title is also recognised over unallocated Crown land in and around Alice Springs which is classified as ‘outer regional’ under ARIA.

- In Victoria, native title land is located ‘remote’ and ‘outer regional’ areas.

- In Tasmania there are no successful native title claims to date.

- New South Wales is the only jurisdiction that has successfully achieved a native title determination in an ‘inner regional’ area. The land parcel is very small comprising 0.1 square kilometers on the New South Wales Coast.

Overall, the land over which native title interests and rights have been recognised is some of the most marginal and inhospitable land in Australia.

The nature of native title interests and rights

Under native title, the majority of groups of traditional owners do not have exclusive possession of the land. While some traditional owners do have what we call exclusive rights to land – approximating freehold rights – the majority of the traditional owner groups share rights to land with other groups of people such as industry, governments and pastoralists. The Indigenous rights to land are limited to access to land to conduct ceremony, and to care for land, and the right to negotiate when future developments are proposed on the land. Native title does not automatically give the traditional owners the right to move onto the land and establish residences or businesses or business infrastructure. This would require negotiation and agreement by government and any other stakeholders.

As we know, many native title claims are still in progress, and resolution of these claims is still a way off. The claimable land that exists under the native title regime includes unallocated Crown lands, some reserves and park lands, and some leases such as non-exclusive pastoral and agricultural leases.

Overall, what can say of all types of land under Indigenous communal tenure? Some may argue that the Indigenous estate is vast – though not as vast as it once was. We do know that land that has been returned to Indigenous Australians is predominantly remote and distant from roads, infrastructure and markets. Land under native title is subject to various caveats in terms of what can occur on the land and requires negotiations with governments and other stakeholders which can take years. This all puts some serious limitations on the enterprise options for the land. It is not a simple matter to start up a business where there are limited or no utilities, no roads and no markets. The enterprise options become limited to pastoral pursuits, the making and selling of art, tourism in some instances, and on land which is rich in minerals, mining perhaps. In some coastal areas aquaculture is possible, and there are examples of Indigenous people providing services to the local communities like building services.

We must also consider that land under land rights and native title is communally or collectively owned by the traditional owners. These tenures are different from the Torrens system where – under Torrens, land is owned by one proprietor or joint proprietors and can be sold or transferred to new owners. Under communal land tenures, land lots cannot be transferred or sold. For that reason, infrastructure is generally not owned, and therefore not bought and sold by individuals. Much of the infrastructure is provided by government. In most instances, development cannot occur on the communal land without the collective approval of a majority of traditional land owners.

So this ends the background information on Indigenous communally owned land. The next aspect that I am going to explore in this paper is the aspirations that traditional owners have for their land.

What do traditional owners want to do on their land?

According to HREOC’s national survey of traditional owners in 2006, above all other roles, traditional owners are most likely to identify as the custodians of their land and seas. This means that for the majority of survey respondents, the most important meaning and function for traditional lands is affiliation, connection to land, and care for country. Out of 39 survey responses that were specific to traditional owners, only 5 respondents, less than 13 percent, identified economic development as a first priority for land. The following quote from a NSW traditional owner was typical of many responses that we received:

Economic development is an important tool in which to gain self determination and independence, but it should not come at the expense of the collective identity and responsibilities to your traditions, nor the decline in health of your country.

SLIDE 3

TOP LAND PRIORITY FOR TRADITIONAL OWNERS

(Click on graph for expanded view)

I would also like to explain that while there were 39 traditional owner responses to the survey, it actually represents a lot more people. We sent the surveys to representative bodies and land councils and they filled out the survey by getting a group or collective response to each question. Each returned survey required the collective endorsement of the representative-body board, or a group of traditional owners with responsibility to authorize the survey responses. And HREOC had a very good response rate from native title representative bodies. When the survey was sent out in 2006 there were 18 representative bodies, we received surveys from 16.

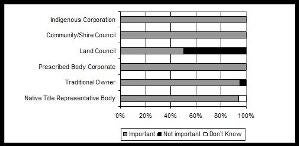

So, back to the survey findings. We know that custodial rights and responsibilities are the most important priority for traditional owners. However, while the majority of traditional owners did not identify economic development as their first priority for land, they overwhelmingly acknowledged its importance.

SLIDE 4

IMPORTANCE OF ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT ON LAND

(Click on graph for expanded view)

Yet while the majority of survey respondents were positive about enterprise development, they almost all described a lack of capacity to develop ideas into action. One traditional owner from Northern Queensland put it this way:

[We have no enterprise] as yet but have plans and need support to develop the ideas. We would like to develop fishing, aquaculture and tourism ventures. We need a management plan to include these ideas.5

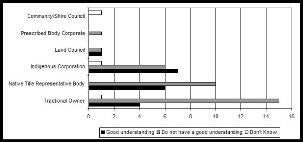

It is obviously necessary to have a level of understanding of land agreements and an ability to negotiate with government and industry to leverage opportunities for enterprises. This is especially important in regions where there are no obvious forms of income and no natural resources that will attract income. Under the native title regime, traditional owners can be parties to Indigenous Land Use Agreements with governments and industry, and these agreements can include enterprise options. Unfortunately, our survey results demonstrate that the majority of traditional owners do not have a good understanding of land agreements as represented in this next slide.

SLIDE 5

TRADITIONAL OWNER UNDERSTANDING OF LAND AGREEMENTS

(Click on graph for expanded view)

It is highly likely that a majority of traditional owners cannot confidently participate in negotiations. This inevitably places limitations on their ability to realise opportunities. Only 25 percent of traditional owner respondents claimed an understanding of agreements, while 60 percent of their representative bodies claimed that traditional owners were able to understand agreements. This raises questions about whether their representatives are aware of their level of comprehension, the extent to which traditional owners are able to give informed consent to land decisions. These factors can impact on the level of commitment and enthusiasm that traditional owners have over the long, drawn out process of land agreements. One traditional owner commented:

Stop giving us tonnes of paperwork that we don’t understand, put it clearly in simplified plain English, otherwise people sign on the dotted line without understanding what they’re signing to.6

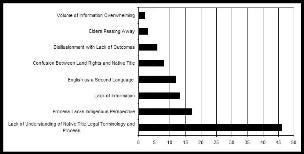

Traditional owners and their representative entities were asked to identify the three most significant factors preventing their understanding of land agreements.

SLIDE 6

TOP THREE REASONS PREVENTING TRADITIONAL

OWNERS FROM UNDERSTANDING LAND AGREEMENTS(Click on graph for expanded view)

The survey responses show that the complex and technical terminology of native title and land rights is the greatest barrier. Almost all survey respondents cited some form of difficulty in understanding agreements and the following comments were typical of many responses:

[The Aboriginal Land Act was set up by lawyers and anthropologists …only the professionals can understand it … [they] become the gatekeepers and owners of our knowledge, they run everything on our behalf.7

And:

We need clear explanations of matters of law, anthropology and political development…The procedures are unfair and biased against Indigenous people. Our people are misled and individuals are paid off to act outside our social and decision-making structures.8

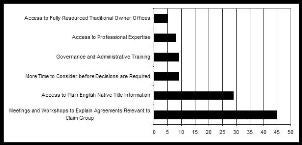

Traditional owners and their representatives were asked to provide examples of actions or resources that would help them understand and participate in land agreements.

SLIDE 7

RESOURCES REQUIRED TO IMPROVE TRADITIONAL

OWNER UNDERSTANDING OF LAND AGREEMENTS(Click on graph for expanded view)

There is clearly a need to run workshops and meetings to explain native title and land rights regimes. This will only be the start. Understanding the agreements is one thing, being about to leverage opportunities from them is another. Survey respondents were asked to nominate the three most important resources required to progress development on land.

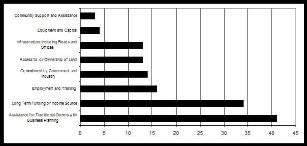

SLIDE 8

TOP 3 RESOURCES REQUIRED TO PROGRESS

ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT ON LAND(Click on graph for expanded view)

Forty two percent of survey respondents claimed that they need skilled personnel to support them. An economic base is required for any enterprise. Thirty nine percent of survey responses identified funding, or an income source, as one of the top priorities to progress and support development on land. 13 percent of respondents identified a need for training and employment.

Survey respondents also identified infrastructure as a major requirement for economic development, including roads, offices, equipment and capital to build. The lack of infrastructure in remote locations of Australia must not be underestimated in any discussion about economic development. And I quote a traditional owner again here:

Infrastructure is needed badly. Our capacity is limited to volunteer work and no professional assistance.9

Some survey respondents identified land ownership as a precondition for economic development. Native title holders with limited rights to land may not have the rights to do much more than access land. The NSW Native Title Services put the argument well by outlining the three most important requirements for economic development on native title land are as follows:

[A] willingness for State Government to purchase or compulsorily acquire land which can form part of a settlement with native title claimants, specifically freehold grants to traditional owners…

[A] willingness of state governments to develop settlements with traditional owners … such as the grant of commercial fishing licenses and water shares.

And, increased funding for personnel and infrastructure to build the capacity of traditional owners to pursue and progress their economic interests on land and water.10

So, given what we know about the nature of the land, given what we know about a sample of traditional owners views about development on land, and what is required to progress economic interests on land, let’s look at what is the Australian Government doing to kick-start economic development.

One of the main platforms of the Australian Government’s economic agenda for communal lands is to make individual leases possible so that Indigenous people can own their own homes. During 2006, the Government amended the Aboriginal Land Rights Act 1976 (Cth) in the Northern Territory to make 99 year leases possible over Indigenous townships. The lease provisions are not unlike those over the city of Canberra. The government holds a 99 year headlease over the township area, and then subleases individual land lots to residents and businesses for a 99 year period. After 99 years the leases can be renewed.

Subleasing has actually always been possible on Indigenous lands. However, the new leases will differ from the old in that they are managed by government rather than traditional owners. The Government’s rationale for taking control of lease arrangements is to give certainty of tenure to non-Indigenous investors, businesses and residents. The thinking goes that business groups are more likely to invest under a government administered lease regime than with traditional owners. Indigenous people will also be able to buy their own homes under the 99 year scheme, and there will be no need to make communal decisions about what occurs on the land. The permission to lease land lots and build infrastructure will be through a government entity. The Government hopes that by offering Indigenous and non-Indigenous people certainty of tenure, they will be creating an economy. Businesses will start in the communities and Indigenous people will have employment opportunities. Indigenous people will join the ‘real economy’ commit to a mortgage and maintain a house asset that they can pass on to their children.

Indigenous communities will not be compulsorily required to agree to headleases. However, the Government is encouraging the agreements by negotiating annual rental payments to families who have the traditional rights to the townships. Additional housing and infrastructure is also being offered to communities that sign to headleases. This is a considerable incentive given that many remote Indigenous communities are chronically short of housing and overcrowding is causing health and social problems.

Once signed, traditional owners can negotiate conditions on a headlease but they will not be able to decide who moves onto their land, nor will they have control over residential, business and infrastructure development under the sub leases.

The Government strategy for remote Indigenous land also includes the reduction of services to smaller, communities of 100 people and less. Both Minister Brough and his predecessor Minister Vanstone have said that Indigenous people in small, remote communities cannot expect to receive government services and they should become part of the wider Australian economy. In 2005, Minister Vanstone said that her Government was no longer willing to support these so-called ‘cultural museums.’11 This means reliance on larger regional townships. You can see the plan here. The Australian Government is hoping to create larger regional centres rather than having to service remote outposts. The larger centres on Indigenous land will have headleases over them and non-Indigenous people will be able to move into these centres and establish businesses and become residents. The teachers, health workers and other service people will be able to buy their own homes on Indigenous land if they so chose.

In order to stimulate home ownership, the Australian Government is intends to build low cost houses in remote communities where there are 99 year headleases. FACSIA has committed over $100 million to increase remote home ownership from 2006 to 2010. Indigenous Business Australia is tendering for contractors to produce ‘flat pack’ assembled-on-site houses for sale at $150 000 for the Indigenous home ownership scheme. Good renters will also have an opportunity to buy the community house they have been living in at a reduced price. The Government also intends to use the CDEP program to start building ‘flat-pack’ houses, to support home maintenance, and to maximise employment and training opportunities.12

While the housing initiatives are described as ‘Australia-wide measures’ they are exclusively available to states and territories if, or when, they amend their land rights legislations to allow for 99 year leases. To quote the Minister for Families, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs:

These programs will be available to all States that follow the Australian and Northern Territory government’s lead to enable long term individual leases on Aboriginal land...13

The Northern Territory is currently the only jurisdiction in a position to access this funding. Other states are beginning the process of reviewing their land rights legislations and it is not certain whether they will include provision for 99 year leases.

The final aspect of the Government’s economic program for communal land is an increase in the number of programs available to support Indigenous business including loans schemes and support funding. These are managed through Australian Government departments, Indigenous Business Australia and the Indigenous Land Corporation. While there are some good programs, the assistance operates on a self access model, and this means that many groups of remote Indigenous Australians are not in a position to apply. Applicants require English literacy competency, business knowledge and management or governance capacity to be successful in their applications. Therefore, only those communities and individuals who are business literate or who have appropriate supports can access these programs. Now, I would like to remind you of an early part of this presentation where I said that the traditional-owner survey respondents told us that they need money to start businesses and skilled personnel to assist them to start up enterprises. It is here were we can see a wasted opportunity. The funds are available, but it is only the well organized communities who are able to access them. The Only representative bodies in some regions of Australia are native title bodies and land councils, and these groups are increasingly stretched by their statutory and funding obligations, and unable to support traditional owners in enterprise development.

Overall, while it is commendable that the Australian Government has made such an intensive effort to improve outcomes for remote Indigenous communities, HREOC’s research demonstrates that the current reform agenda will not provide benefit to the vast majority of remote Indigenous Australians. In fact it has potential to do great harm. The reasoning is as follows:

- Increasing contact between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people is not a strategy in itself to stimulate Indigenous economies. Despite access to employment and all of the benefits of a ‘normal’ economy in towns like Alice Springs, Moree, Port Augusta and many of the other large townships across Australia, social and economic dysfunction continues. For remote Indigenous people, relocation to town camps on the fringes of townships can increase, rather than alleviate alienation and dysfunction.

- Basic economic modeling demonstrates that the Australian Government’s expanded home ownership scheme will be out of reach of the majority of remote Indigenous households. While the scheme may advantage some Indigenous families, the policy will only be effective for families already able to access current programs such as the Indigenous Business Australia home loan assistance scheme. There is no clearly articulated public housing policy for families who are unable or unwilling to purchase a home

- The home ownership scheme will transfer the considerable costs of remote housing maintenance to Indigenous people on low incomes. ‘Cost effectiveness’ is the most important design parameter for ‘flat-pack’ houses to be built for home ownership in remote communities. Given that structural problems and climatic conditions are proven causes of the majority of maintenance requirements in remote Australia, low cost housing is likely to exacerbate these problems. Low cost housing is also likely to be more expensive to heat and cool in some of the harshest environments in Australia. In this context, home ownership is likely to put considerable economic strain on low income households.

- International experiences demonstrate that individualising Indigenous communal tenures such as those proposed through the 99 year headleases leads to the loss of Indigenous owned land. The economic benefits are marginal and short-term, and do not compensate in the long term for loss of traditional lands.

- Most Indigenous land tenures are located in very remote desert country, distant from markets and infrastructure to support enterprise development. The current Australian Government policy will not have any impact on these communities.

- Many remote communities currently lack the governance, capacity and skill to access Australian Government enterprise development incentives. In order to be able to apply for funds, applicants must have competent English literacy and financial literacy skills, and be able to develop business plans and grant applications. Many communities require targeted intervention to get to a point of gaining any benefit from policies under the Government’s self-access model.

- In the majority of remote communities, Indigenous people are not likely to be competitive in an open employment market. Australian Bureau of Statistics data demonstrates that private enterprise is not a reliable employer of Indigenous people. In remote contexts, private enterprise will be under no obligation to employ Indigenous people, the majority of whom have limited skills and education. Given that secondary education is only now being rolled out in remote Australia, Indigenous people are disadvantaged in competition for employment.

Essentially, the Government’s economic strategy for remote areas will only be successful in a minority of Indigenous communities with good governance systems and personnel capable of accessing government subsidies and grants. Communities that are well resourced and well organised may be able to leverage additional benefits for Indigenous residents. Coastal communities on fertile land may also be attractive to investors and attract external business interests under the Government’s reforms. Clearly, the benefits of the Government’s strategy are directed primarily to individuals and communities that are already advantaged or to non Indigenous businesses and investors who want to access Indigenous lands for economic gains.

It is likely that communities on marginal land with no history of enterprise development will continue to find themselves economically isolated. And I am thinking here of communities like those in the Great Sandy Desert of Australia. Investors and businesses are never likely to move into desert areas like these and create an economy. There will never be markets for housing in these areas, and Indigenous people who take up home loans will be part of a debt creation strategy. When you think about it, home-ownership is only a wealth creation strategy when you sell your home and you have made some profit; some capital growth.

In its current form, the Australian Government’s economic reform agenda is not targeted to the remote Indigenous communities most in need, where there is compound disadvantage including:

- poor governance or a lack of governing bodies;

- low levels of English literacy;

- reduced access to education and training relevant to support employment;

- marginal land that has not provided income to date and is unlikely to do so in the future; and

- poor community infrastructure.

In conclusion, and on a brighter note, while the Australian Government’s approach is cumulatively distancing Indigenous people from participation, management and governance of their affairs, there are some good practices across Australia that support Indigenous controlled processes for economic development.

For example, the Yarrabah community close to Cairns is establishing its own 99 year lease scheme over its township as well as allowing for home ownership, local employment, and enterprise development. While this approach is similar to that of the Australian Government, it has one important difference. The Yarrabah 99 year lease is managed by the local Aboriginal Shire Council. The entire Yarrabah community is invited to participate in discussion and decisions about what happens on the land and about economic development opportunities. This is a model of participatory self management, in contrast to the Australian Government model which will remove autonomy and local self management. Yarrabah is developing its own construction company, Y-Build to construct the houses for sale to local residents. We can only hope that projects such as these receive the support of governments and the lease arrangements are not undermined as they have been at Wadeye and Alice Springs.

There are also some spectacular successes like Ngarda Civil and Mining. Ngarda Civil and Mining is an Indigenous-owned and run company in Port Headland that started out with 6 whipper-snippers, providing services to the mining industry. It is now a multi-million dollar business providing a wide range of mining services. Its workforce is over 80 percent Indigenous. It continues to be expertly managed and owned by Indigenous people and it is providing community development services to its own community.

Tom Calma’s Native Title Report 2006 contains more detail about these cases as well as additional case studies that demonstrate what is possible when Indigenous governance is fundamental to agreements and enterprise development.

The preservation of Indigenous rights to land and an emphasis on Indigenous participation in policy formulation and implementation are the key factors in the success of all of the case studies. These principles and practices should be the starting point of all future government activity to support economic development on Indigenous land.

Thank you.

ENDNOTES

1. Note: The majority of traditional owner respondents to the 2006 HREOC survey agreed that economic development is important for their land. However, when asked to rank the most important uses for land, traditional owners supported ‘custodial responsibilities’ and ‘access to land’ before economic development.

2.National Native Title Tribunal Correspondence with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner, Email, 22 January 2007

3. Office of the Registrar, NSW Aboriginal Land Rights Act, Correspondence with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner, Email, 31 January 2007, p1

Note: Lands granted to Local Aboriginal Land Councils in New South Wales are of high commercial value due to their development potential for either residential or commercial use. The land claimed under the NSW Aboriginal Land Rights Act 1983 is currently valued at approximately $800million. This is despite the fact that land parcels claimed in NSW are relatively small when compared to jurisdictions like the Northern Territory.

4. Traditional owner from the Yorta Yorta Nation Aboriginal Corporation, Survey Comment, HREOC National Survey on Land, Sea and Economic Development 2006

5. Traditional owner of the Umpila territories, Cape York, Survey Comment, HREOC National Survey on Land, Sea and Economic Development 2006

6. Traditional owner from North Queensland (not specified), Survey Comment, HREOC National Survey on Land, Sea and Economic Development 2006

7.Traditional owner of the Umpila territories, Cape York, Survey Comment, HREOC National Survey on Land, Sea and Economic Development 2006

8. Traditional owner of the Gubbi Gubbi and Butchulla territories, Survey Comment, HREOC National Survey on Land, Sea and Economic Development 2006

9. Traditional owner of Gubbi Gubbi and Butchulla territories, Survey Comment, HREOC National Survey on Land, Sea and Economic Development 2006

10. NSW Native Title Services Ltd, Survey Comment, HREOC National Survey on Land, Sea and Economic Development 2006

11. Vanstone A, (Former Minister for Immigration, Multicultural and Indigenous Affairs), Indigenous communities becoming 'cultural museums', ABC Radio, AM Program interview, 9 December 2005, available inline at: http://www.abc.net.au/am/content/2005/s1527233.htm, accessed 15 March 2007

12. Vanstone, A., (Minister for Immigration, Multiculturalism and Indigenous Affairs), Initiatives support home ownership on Indigenous land, Media Release, 5 October 2005 available online at, http://www.atsia.gov.au/Media/former_minister/media05/v0534.aspx accessed 20 February 2007

13. Brough, M., (Minister for Families, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs), 2006 Budget Summary of Indigenous Measures (Fact Sheet), available online at, http://www.atsia.gov.au/Budget/budget06/Fact_sheets/factsheet08.aspx accessed 20 February 2007