Australian Institute of Building Surveyors Conference

Australian Institute of Building Surveyors Conference - Earth, wind, fire and water - engaging the elements

Dockside, Cockle Bay Wharf, Sydney

24 - 25 July 2006

Michael Small, Senior Policy Officer, HREOC

Introduction

I would like to start by thanking Bill Burns and the NSW AIBS for this invitation to address your annual conference on an issue that over the next few years is going to see significant changes in the way we design, construct and manage the buildings we use for work, education, entertainment and service delivery.

These changes will directly affect Building Surveyors in their role as certifiers of new buildings and changes of use and upgrading of existing buildings.

It will involve changes to the Building Code of Australia (BCA), new technical provisions in referenced deemed-to-satisfy Australian Standards and the adoption of a national anti-discrimination standard on access to buildings.

For these changes to be effective Building Surveyors will need to learn new skills, upgrade existing knowledge and apply renewed vigor to the certification process.

Building Surveyors will, more than ever, be the final gatekeepers to ensuring our built environment meets the ever growing need for safe and equitable access.

Areas to be covered

- The story so far .. harmonising BCA and DDA access provisions

- Earth wind fire and water .. the four elements of ensuring good access

- The good, bad and ugly .. the importance of getting it right

- Making it happen .. Skills for the future

The story so far

Even before the federal Disability Discrimination Act (DDA) became law in 1993 it was clear that there were inconsistencies between the access provisions of building law, as required by the BCA, and the non-discriminatory provisions of discrimination law.

For example, while the BCA only requires one accessible toilet for every 100 pans the DDA provisions would allow a person requiring the use of an accessible toilet to lodge a discrimination complaint if, for example they had to travel down 6 storeys of a building into the basement to locate that toilet, while you and I had to simply walk round the corner.

Similarly, under the current BCA there is no requirement for lift car announcements to announce which floor the lift has arrived at, which means that a blind person, for example, has no way of knowing if they have arrived at the floor they want. This also could be the subject of a discrimination complaint.

The inconsistencies are not limited to those areas where access requirements do not currently exist in the BCA. It also exists in questions of degree of access. For example, if this conference room was being built today the current BCA would require a hearing augmentation system be fitted to ensure people with a hearing impairment could better access the presentations. However, the current BCA requirement only requires a minimum of 15% of the area be covered by that system. If someone with a hearing impairment was sitting outside the covered area and could not hear the presentations they could also lodge a discrimination complaint.

These are not inconsequential inconsistencies for people with disabilities. They mean the difference between being able to independently participate in the economic, social and cultural life of our community and being excluded from participation.

These inconsistencies have also been of concern to the building industry.

Designers, builders, owner and operators and managers of buildings have all faced the possibility of complaints, even if their buildings comply with the BCA.

Similarly those involved in the development approval and building certification processes have expressed concerns about what they must do to ensure they are meeting their responsibilities, particularly after the Cooper v Coffs Harbour Council case which showed that those involved in permitting developments, which were later shown to be discriminatory, could themselves be subject to a complaint.

In 2000 the Federal Government began a process to try and resolve these inconsistencies by changing the DDA to allow for a Disability Standard on Access to Premises (Premises Standard) which would more clearly define the level of access that must be provided to meet responsibilities under the DDA.

At the same time the Federal Attorney-General asked the Australian Building Codes Board (ABCB) to develop the draft Premises Standard and changes to the access provisions of the BCA so that the two mirrored each other.

The effect of doing this would be that when completed compliance with the BCA would ensure compliance with the Premises Standard and therefore with the requirements of the DDA.

The great advantage of this approach would be that designers, builders, owners and operators could continue to rely on the regulatory framework they were used to, the BCA, without the need to refer to a separate and different regulatory tool - which is the case in most overseas countries where building and anti-discrimination requirements remain separate.

Similarly those involved in building certification could continue to rely on the BCA as the primary benchmark against which to assess developments and have the confidence that they would address their liabilities under the DDA through a vigorous application of the BCA.

This process started six years ago and its completion is well overdue.

I am sure you can imagine, however, how difficult it has been to negotiate hundreds of changes, some minor and some very significant, to the BCA and its referenced Australian Standards.

The good news is that a draft is now with the Attorney-General - the bad news is that there were a number of issues where consensus just could not be achieved and final decisions have yet to be made on which way to move forward on those outstanding issues.

Having said that the Commission is confident this project will be completed soon and that the benefits for people with disabilities, the building industry and certifiers will be worth the wait.

Earth wind fire and water

To pick up on the theme of this conference I would like to focus on the four elements of ensuring good access through the design, approval, construction and certification processes.

While compliance with each aspect of the BCA is vital to ensuring a safe and usable built environment access is one of the areas where a precise application is most critical and unfortunately, in our experience, most lacking.

Successful application of the deemed-to-satisfy provisions or effective Alternative Solutions can mean the difference between being able to get into and safely move around a building and being discriminated against.

- A well designed and compliant ramp means that most people can independently access a building. Even small variations from the compliance requirements can mean a ramp becomes a barrier to access.

- Effective application of the tactile ground surface indicators means the difference between safe movement around hazards and painful encounters with obstacles or serious injury from falls.

- Properly fitted out accessible toilets mean that people can be confident they can go out and use a toilet when necessary. A handrail put in upside down can mean the toilet is unusable.

- A compliant doorway requiring minimal effort to open means that a person using crutches or an older person can get into a building. A heavy door or revolving door can mean someone is left out on the pavement.

Achieving compliance relies on all partners in the process understanding the requirements of the BCA and other relevant regulation and standards, and ensuring they are applied.

Earth - design

The first gatekeeper to ensuring compliance is the designer, both at the concept stage prior to development approval and the later detailed design stage prior to construction.

If the designer is not fully aware of access requirements they will cause themselves and their client many headaches down the track when changes to the design are required to eliminate barriers.

These changes can be both expensive to make and frustrate the achievement of the overall concept of the project.

A thorough knowledge of access requirements means that access can become a feature of the design and not an add-on begrudgingly provided at a later stage.

Wind - approval bodies

The second gatekeeper is the approval body that can impose a number of requirements on the project in addition to BCA compliance.

At this stage in the process a thorough knowledge of access issues can assist in the early identification of potential problems and can alert those responsible for the project to issues that need to be re-visited.

The approval body can also add to the overall accessibility of the project by raising issues such as building location and orientation on the allotment to maximise accessibility to surrounding infrastructure and associated buildings.

They can also identify how design solutions might add to or detract from wayfinding within the project which is not extensively covered by the BCA, but is non-the-less an important aspect of good design.

Fire - construction

The third gatekeeper is the team that is responsible for constructing the building. In some ways this gatekeeper is the one that most critically needs to understand the access specifications and how to apply them.

It is during the construction phase that thresholds designed to be compliant become non-compliant, fixtures are put in upside down and safety features are put aside.

Good compliance through the construction phase requires good communication between the project management and builders. If compliance is not achieved considerable cost can be incurred in retro-fits to address any barriers.

Water - building certifiers

The final gatekeeper - and the one that sometimes has to plough through the earth, brace against the wind and pour water over the fire - is the building certifier.

I note that the draft Core Performance Criteria for accreditation clearly state that building certifiers must have core skills including the ability to:

Identify, access, read, interpret and determine compliance with legislative requirements (eg Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979, BCA, development standards, development consents, council development control plans, council guidelines, codes, standards and specifications relevant to the category of accreditation (including health and safety aspects)

Assessing compliance with the BCA and other relevant codes or standards is the bread and butter of your profession.

As I have stated earlier in order to achieve compliance with the BCA in the area of access it is vital that attention is given to the detail of final construction as well as broader compliance questions such as numbers of toilets and number of accessible entrances.

It is the detail that provides for access or makes a building inaccessible.

Unfortunately far too often it appears to us that many of the gatekeepers in the process of design, construction and certification of buildings do not have the level of understanding required to ensure compliance with the BCA in the area of access.

Indeed sometimes we are left wondering if some of them have copies of the BCA or its referenced Australian Standards to work by - and here I speak from experience of having had hundreds of calls from architects, local government and private certifiers asking for either copies of the relevant Australian Standards or my advice on what the BCA requires.

The good, bad and ugly

Just to illustrate a few examples of good and not so good design and construction, all of which received certification, I would like to go through a few slides I have collected recently. (My thanks to Mr Murray Mountain who provided some of the photos; all comments are my own responsibility.)

1. Accessible toilet with good compliance

In this example there is good circulation space and the rail provides support and guidance leading down towards the pan. Compare this with the next picture.

2. Toilet handrail wrongly installed

3. Handrail with good compliance

Here the end of the handrail correctly has been turned to lead hands on or off and to avoid painful contact with sudden or sharp ends or edges. But compare the next picture ... .

4. Non-compliant handrail

Ouch!

5. Steps and TGSI with good contrast

Here the light TGSI cones and stair nosings provide a very clear contrast with the darker floor and step surfaces. Compare however the next picture.

6. Poor contrast in polished stone surface

Hopefully it is obvious to this audience at least how dangerous and confusing these steps are with the shiny polished surface and poor contrast for the TGSIs and step noses.

7. Non-compliant glass doorway

The lack of a continuous contrasting strip between 900 and 1000mm high makes this glazing dangerous particularly for people with low vision.

8. Non-compliant main entrance: no threshold ramp

A sloping external footpath need not prevent access where a compliant threshold ramp can be provided.

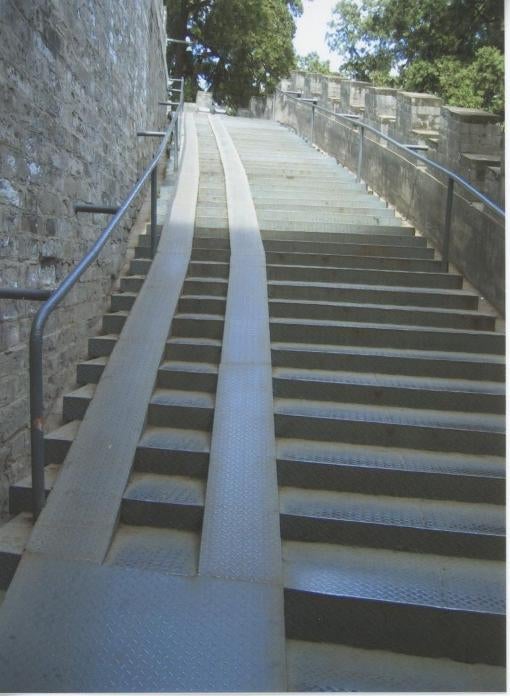

9. Non compliant entrance with ramp

Here while a ramp has been provided it has compliance problems. Is there room on a level surface to execute the turn into the doorway? There is no TGSI warning of the steps and although a handrail has been provided for guidance and support it is not compliant - again, look at the ends.

10. Doors opening onto landing

Here a ramp entrance is made non-compliant by the doors opening outward into the space from which a person is trying to enter.

11. Ramp with no handrails or other safety features and small landing

The non-compliant ramp here has no handrails, safety edges or TGSI and the landing is too small to execute the 90 degree turn in or out of the door.

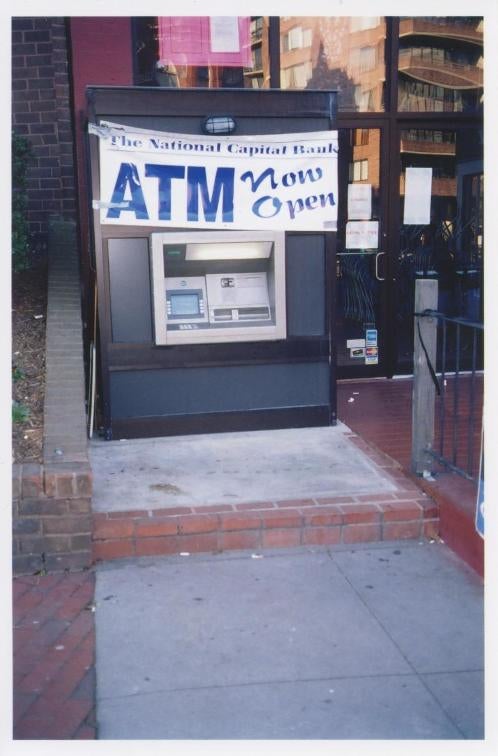

12. Step right up

Despite the banner this ATM is clearly not open for business if you can't manage a sizeable step up.

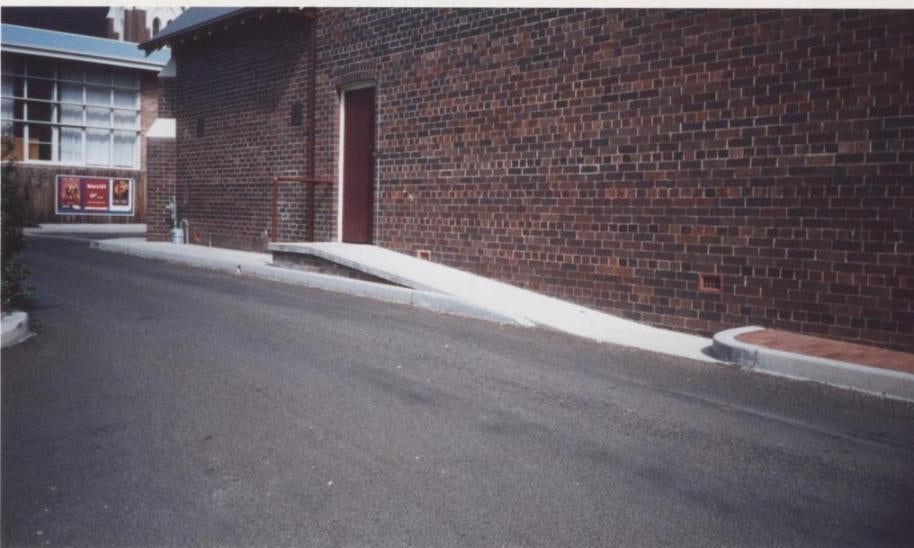

13. The perfect ramp?

Every picture tells a story and in this case words fail.

14. Accessible escalators

As shown in slide number 13 not every ramp is among the "good" when it comes to access - sometimes poor design or implementation can made it bad and ugly. But to close the slide show here is a good installation of warning TGSIs at escalators. Of course escalators can't be part of a sole access path because of the barrier they present not only to wheelchair users but also to many other people with disabilities - but it is important that they are still as accessible as they can be.

Note that there is good contrast here both with the floor tiles and with the escalator itself.

These issues of contrast demonstrate that best practice in access doesn't always have to cost a fistful of dollars - it may not always even cost a few dollars more if the right decisions are made early on. The development of a DDA Premises Standard is intended to help this happen.

Making it happen

Industry will have to respond to significant changes to the BCA and associated Australian Standards over the next couple of years as the Premises Standard is finalised and implemented.

This provides us all with an opportunity to look closely at the skills required by designers, approval bodies, builders and certifiers in order to effectively understand and apply deemed-to-satisfy or Alternative Solutions to access requirements.

This might involve looking at the professional accreditation core skills and knowledge base for people coming into the profession and for the continuing education of those already practicing.

It might also involve looking more closely at the process by which building certifiers notify developers of non-compliance and how compliance is achieved.

And on the other side of the coin it might also involve looking at processes to improve how the profession monitors its members performance in certifying compliance.

Conclusion

Completion of the project to develop a Premises Standard and changes to the BCA will result in significant improvements in the built environment for people with disabilities, families, business and our growing aged population.

I am sure I don't need to remind you that short of an untimely death the changes will benefit all of us as we grow older, loose our sight, our hearing or our capacity to move around as we used to.

Making it happen, however, relies on each of the gatekeepers doing their job with precision and is dependent on the final gatekeeper - the building certifier - having the skills and knowledge base to ensure compliance is achieved.

Over the next few months the Commission will seek to discuss how this can be best achieved with the AIBS and other professional associations so that when the changes occur your members are equipped to deliver the goods.