Rights of children in schools: a human rights perspective on behaviour

Introduction

Thank you, Dr Anna Sullivan, for the kind introduction. And thank you to the University of South Australia’s School of Education for inviting me to deliver this lecture on Rights of children in schools: a human rights perspective on behaviour.

I would like to acknowledge the Traditional Owners of the land we meet on today.

It is on their ancestral lands that the University of South Australia campus is built, and I would like to pay my respects to elders, past and present. I also acknowledge other Aboriginal people here today.

I am delighted to be part of this National Summit to raise the profile of children and their rights as students in schools. It is an honour to participate with colleagues committed to finding school practices that seek to engage the views and participation of students, and developing practices that draw on the rights of children.

The Role of the Commissioner

First, I’d like to tell you a little bit about my role as National Children’s Commissioner. I was appointed in the role of Australia’s first National Children’s Commissioner around 15 months ago. The responsibilities of my role are set out in the Human Rights Act and I work at the Human Rights Commission alongside other Human Rights Commissioners who cover areas like sex, age and race discrimination, and the rights of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Some of my key duties are to:

- Be a national advocate for the rights and interests of children and young people – this includes all children and young people up to eighteen years of age.

- Promote children’s participation in decisions that impact on them.

- Provide national leadership and coordination on child rights issues.

- Promote awareness of and respect for the rights of children and young people in Australia.

- Undertake research about children’s rights.

- Examine laws, policies and programs to ensure they protect and uphold the rights of children and young people.

A major part of my role involves submitting a yearly report to the parliament and this gives me an opportunity to alert the community to human rights issues and concerns for children and young people.

The Big Banter

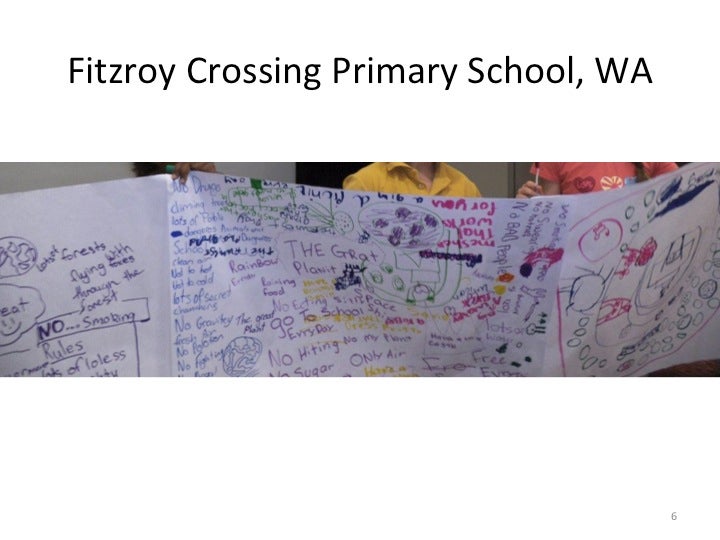

My first priority as Commissioner was to conduct the Big Banter listening tour – the goal was to hear from children and their advocates about what issues are most important for children.

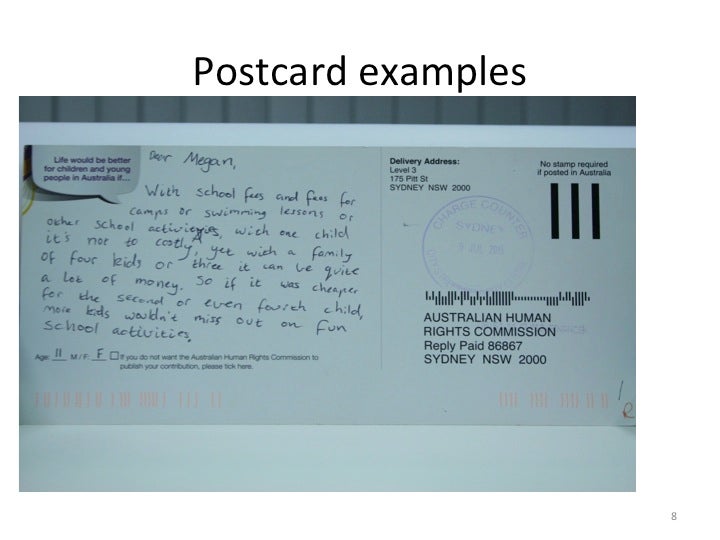

Through the Big Banter I met with well over 1,000 children face-to-face, and heard from over 1,300 children online and through the post. I’ve also heard from hundreds of children’s advocates.

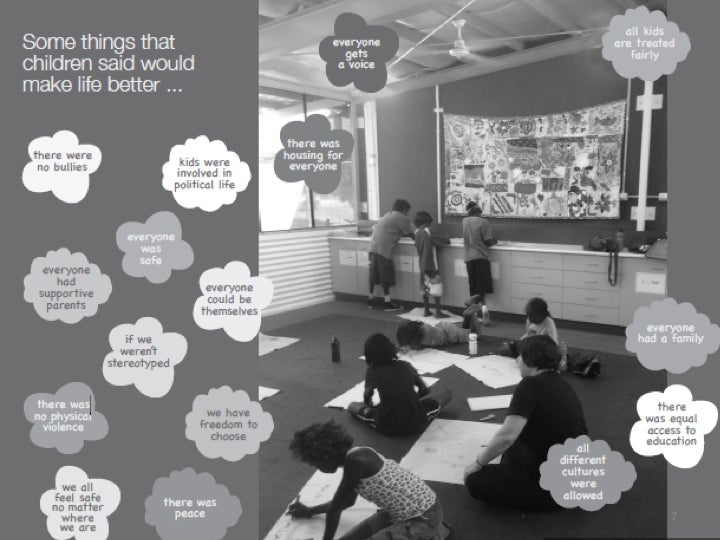

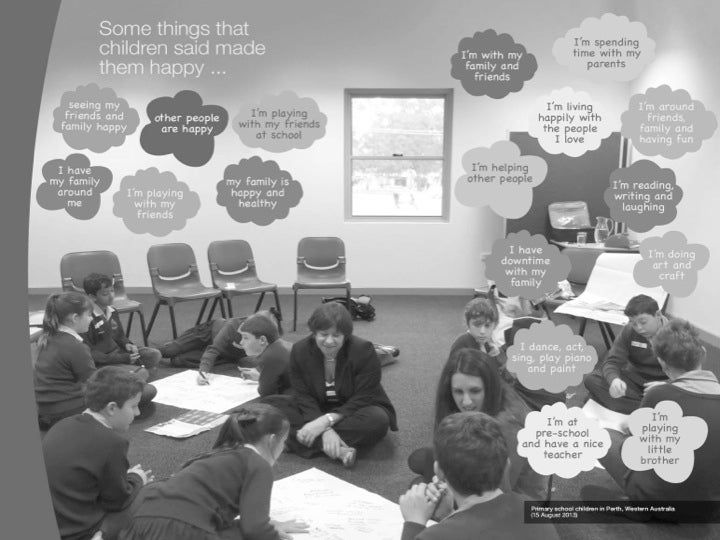

During the listening tour, many different issues were raised. Primarily, however, children and young people said that they want to be safe and spend time with their family and with their friends. They are concerned with the level of violence and aggression and bullying in the community, and they would like to live free from drugs, alcohol and smoking.

Some children and young people worry about not being able to afford to do or have the things they would like, and they want more things to be available for free. They also worry that other children may not be able to afford or access all the things they need. They have an innate sense of fairness and caring for others.

And they definitely want to have a say. They had many exciting ideas about how life could be better, including how they themselves might become more engaged in policy, politics and community.

I went to lots of schools all across the country. Here are just some of the things that kids spoke to me about:

Themes from my 2013 report to Parliament

I used the words and ideas of children and young people I spoke to, along with those of adults, to set out five key goals or themes to guide my work during my five year term.

The first relates to the right to be heard: This is about ensuring young people can participate in decisions that affect them, including making sure that they have access to dispute resolution mechanisms.

The second theme is about delivering a community free from violence, abuse and neglect. Too many children and young people in this country are exposed to violence or are the victims of violence. For example, it is a national shame that by 2013 there were 40,624 children in out of home care due to neglect or abuse, a figure that has almost doubled since 2003-2004.1 We need to do much better at delivering safe environments for children within families, communities and institutional settings.

As you know, not all children and young people have the opportunity to thrive. Even in a rich country like Australia, some children and young people live in poverty, have poor health, live in unstable and overcrowded housing, are disconnected from school and experience social exclusion and isolation. So my third theme goes to ensuring that vulnerable children and young people have every opportunity to reach their full potential and have their rights protected along with their peers.

The fourth theme relates to engaged citizenship: children and young people need to know about their rights and the rights of others, and should be encouraged to take an active role in the realisation of those rights.

The last theme that I outlined in my report is ‘action and accountability’. At present Australia has limited ways of systematically thinking about the rights of children and young people in framing policies, programs and laws and I want to change that around. We also need to do much better at tracking how we are doing in protecting and advancing the rights of children and young people. Improving this is a long term goal I have set for my role.

I’d like to say a little about the Convention on the Rights of the Child because this is the fundamental platform for my work.

The Convention on the Rights of the Child

The Convention on the Rights of the Child is the most ratified international human rights treaty in the world. It has significantly changed the way that children and young people are thought about and are cared for on a national and international level. The Convention establishes that children and young people have the same human rights as adults, but are also entitled to special protection due to their unique vulnerabilities. The rights that children and young people hold are intrinsic to their lives and healthy development – like the right to be safe, the right to care and support, to a family, to education and health care, to a home, the right to express yourself and be heard.

Australia ratified the Convention way back in 1990 and in doing this promised to protect and uphold the rights of children.

It is astounding that it took 23 years before Australia appointed a National Commissioner to advocate for the advancement of the rights of children and young people set out in the treaty Australia signed up to all those years ago.

And while Australia is generally a good place for children and young people to grow up in, it does mean we are behind in a number of areas. Many of these were set out by the Committee on the Rights of the Child when it commented on Australia’s progress in 2012, and I included a summary of these in my first report. Conventions like the Convention on the Rights of the Child are supported by a particular UN Committee that focuses on that Convention and the rights contained in it. Australia, like other countries, must front up to this Committee every five years, and is next due to report in 2018. I hope to achieve a much better report card next time around.

CRC – general principles

The Convention includes four ‘general principles’ considered pivotal to the implementation of all other rights contained within the convention. These are:

- The right to non-discrimination (Article 2)

- The child’s best interests as a primary consideration (Article 3)

- The right to life, survival and development (Article 6)

- Respect for the views of the child (Article 12).

I want to particularly highlight Article 12. This gives to every child and young person the right to be taken seriously and be heard in matters affecting them. These views should be given weight in accordance with the child’s age and maturity.

In 2012 the UN Committee acknowledged that Australia has put some mechanisms in place for the participation of young people, but that significant gaps remain, in particular for children under 15 and in schools.

I am especially interested in how we can promote meaningful participation of children and young people in the decisions and processes that affect them, at both the individual level but also in terms of government policies and laws.

This is especially important for children in vulnerable situations, like those involved in care and protection systems, juvenile justice, and family court proceedings where the decisions that are being made have a significant impact on their lives, both immediately and in the long term. In this sense, being able to be heard, raise concerns, and be taken seriously acts as a strong safeguarding measure for children.

But hearing from children is not only empowering for them, it helps adults to get things right. Every day, policies, programs and laws are being shaped that impact directly or indirectly on children and young people. As the experts in their own lives, ignoring their experiences and perspectives will invariably lead adults to intervene in ways that just don’t work.

CRC – Article 28 & 29

Article 28 of the Convention places a special emphasis on the right of all children to education, and the importance of children being active players in the learning process rather than simply recipients of knowledge.

It provides that:

- Primary education should be compulsory and free (Article 28(1)(a))

- Secondary education should be freely accessible and reflect and address a variety of needs and interests (Article 28(1)(b)-(d))

- Schools should promote regular attendance (Article 28(1)(e))

- School disciplinary measures should respect children’s dignity and reflect the general values of the Convention (Article 28(2)).

Article 29 sets out the aims of education which includes the development of:

- the full potential of the child in relation to their personality, talents and mental and physical abilities

- respect for human rights

- cultural identity and affiliation

- a sense of responsibility towards others, and respect for diversity

- respect for the natural environment

UN Committee’s General Comment No 1: The Aims of Education

We can look to the Committee on the Rights of the Child’s General Comment 1 (GC1) for more comprehensive guidelines to fulfilling our obligations under Article 29 of the Convention.

The values and aims set out under Article 29 provide crucial guidance on how education can develop not just a child’s formal level of knowledge, but also their personal ethical obligations towards society generally.

The Committee advises that Article 29 should not be viewed as a standalone, exhaustive list of the aims of education, but should be viewed in the context of the CRC as a whole. For instance, ensuring that education develops a child’s respect for their cultural identity and national language also upholds the principle of the best interests of the child enshrined in Article 3.

The Committee stated that “The overall objective of education is to maximise the child’s ability and opportunity to participate fully and responsibly in a free society.”2 The broad language of Article 29 affords much flexibility in how this overarching objective can be met, and allows for a balanced approach to placing the child at the centre of education.

The Committee provides a few practical suggestions on how we can integrate these values. These include:

- Re-writing national school curricula

- Frequently and consistently updating textbooks, teaching materials and school policies

- Training teachers, child education workers and school administrators in the implementation of Article 29

- Ensuring that teaching methods further Article 29 and the general objects of the CRC

These kinds of mechanisms can help to ensure that children’s rights are fundamentally protected and upheld by the education system, and not imposed in a fragmented and arbitrary way.

The importance of connectedness

Understanding the behaviour of children within each child’s developmental journey and in the context of their lives is fundamental to ensuring that their needs and rights can be adequately addressed.

Research by Chapman et al. (2013)3 suggests that schools should aim to foster school connectedness in children. School connectedness is defined by “the extent to which students feel personally accepted, respected, included and supported by others in the school social environment” and varies widely depending on the school environment.

School connectedness

School connectedness has a positive effect on school attendance, academic achievement, and the emotional and physical health of children. There is also a correlation between high levels of connectedness and a reduced likelihood of engaging in risky behaviour as an adolescent. Conversely, children experiencing a lack of school connectedness tend to engage in risk taking activities such as alcohol consumption, drug use, cigarette smoking, delinquency and violence.

In this way, school connectedness is a “protective factor” in reducing adolescent risk taking behaviour and related physical or mental harm. It is therefore critical that schools create an environment that enhances a child’s sense of school connectedness if they are to develop their personality, talents, and mental and physical abilities to their fullest potential, in accordance with the Convention.

Chapman found that students who felt that they had some level of influence over school administration and policy (by being a member of a student representative council, for instance) had higher levels of school connectedness. This is a concrete example of how nurturing a child’s talents and mental abilities (Article 29(1)(a)), developing their sense of responsibility for others (Article 29(1)(d)), and encouraging them to freely express their own views (Article 12) enhances a child’s natural affinity with their school environment. In turn, children feel a greater sense of belonging and internalise “pro-social school values”4 such as resilience, responsibility and student caring. As I have visited schools around Australia it is clear the moment you walk in the gate which schools have achieved this connectedness, and there is a palpable difference in the behaviour and attitudes of the students in those schools, right across the student body.

Chapman also identified factors that could increase feelings of school connectedness in students. These include the enforcement of disciplinary policies, efficient classroom management and fostering positive relationships between students and adults.5 Article 28 suggests that school discipline should be administered in a way that respects a child’s human dignity and the core values of the Convention. If schools are to implement disciplinary measures to increase school connectedness, these must reflect the Convention’s standards of respect, dignity and non-violence in relation to children.

In order for schools to be administered in a way that protects and nurtures a child’s human dignity (Article 28(2)), greater focus on the psychological needs of students is needed.

We know that schools are crucial to the development of a child’s physical, intellectual, emotional and mental wellbeing. Today’s generation of young people face numerous and complex stressors that as adults we need to understand much better if we are to assist young people successfully navigate their school years and beyond. For example Mission Australia, in its annual youth mental health report found that while in 2008 20% of young people said coping with stress was a major issue, by 2012 this had jumped to 40%.6

Quote from 16 year old girl

As a 16 year old girl who responded to my survey last year said, “I know kids of my generation are exposed to so many distractions nowadays and it’s incredibly hard to concentrate on school work and that leads to more stress.”

Apart from families, schools and teachers are often the first to know something is going wrong for a child. School-intervention is one of the most effective ways to address and prevent the development of emotional or behavioural disorders .Yet all too often the first response is suspension or exclusion, and we know this is an increasing trend. This impact of this in the worst of cases is entrenched behaviours, disconnection from school, and ultimately denial of one of the most basic of child rights that has major implications throughout the life course – the right to an education.

In fact, one study by Legal Aid NSW analysing the 50 highest users of legal aid services, shows that 80% were 19 years or younger. Three quarters had used drugs or alcohol, nearly half had a mental health diagnosis, 72% had experienced abuse or neglect. More than half had been homeless, just under half had been in care and 94% had spent time in a juvenile detention facility. As many as 82% had been excluded, suspended or expelled from school and, of the files on which a high service user’s highest educational attainment was noted, just under two thirds had left school in Year 9.7 These stark figures remind us how badly multiple systems - of health, housing, justice, education and care – can fail young people.

The literature review “Meeting the psychological and emotional wellbeing of children and young people: models of effective practice” prepared by Urbis examines the effectiveness of school counselling services for children and suggests ways in which these services can better address trends in children’s psychological and emotional health.8

The review generally recommends that student mental health services should accommodate for the diversity amongst the student body, and should not adopt a one size fits all approach. Mental health or behavioural management programs in schools could benefit from addressing the specific needs of:9

- ATSI students

- Students from culturally and Linguistically Diverse (CALD) backgrounds

- Students with disabilities

- Same-sex attracted students

- Gender differences

This kind of approach will better prepare children for a responsible life based on the values of understanding, peace, tolerance, equality of sexes, friendship among all peoples, ethnic, national and religious groups and persons of Indigenous origin.

Inquiry into self-harm and suicidal behaviour in children

I would like to conclude by referring to an investigation I am currently undertaking on intentional self-harm and suicidal behaviour(s) in children and young people. In part this arose from some of the feedback I received during the Big Banter, but also because of the alarmingly high rates of suicide and self-harm among Australia’s young people today.

Intentional self-harm and suicidal behaviour in children and young people is a serious issue in Australia and overseas. The latest available data from 2012 shows that intentional self-harm was the leading cause of death among Australian children and young people aged 15 to 24.10

And, for the same year there were 10,699 instances of hospitalisations involving intentional self-harm for children aged between 5 and 24.11

We know that many more children and young people intentionally self-harm than present to hospital. In 2012, the Kids Helpline responded to 15,887 contacts by children and young people aged 5 to 25 who were assessed to have self-injury and self-harming behaviours.12

The aim of the project is to gain a much deeper understanding about what is happening for our young people, and what can be done to improve supportive interventions and increase help seeking behaviour.

To date I have sought written submissions, held a number of roundtables and engaged in a range consultations across Australia. I encourage those of you who are interested or have a story to tell to email me at kids@humanrights.gov.au and make a contribution

Concluding points

I would like to thank you for inviting me here today. I wish you well as you explore ways to better understand and respond to the behaviour of contemporary young people in schools, so that all children can get the very best education possible. I look forward to reconnecting up with how you have progressed at the panel discussion tomorrow. Once again, thank you.

1 Report on Government Services 2014, Volume F: Community Services, available at: http://www.pc.gov.au/gsp/rogs/community-services.

2 UN Committee on the Rights of the Child (CRC), CRC General Comment No. 1: The Aims of Education, 26th sess, 17 April 2001, CRC/GC/2001/1 [3]

3 Rebekah Chapman et al, ‘School-based programs for increasing connectedness and reducing risk behaviour: a systematic review’ (2013) 25(1) Educational Psychology Review

4 Chapman et al, above n 3, 24.

5 Chapman et al, above n 3, 24.

6 Mission Australia, Mental Health: The Facts (2014) <https://www.missionaustralia.com.au/what-we-do-to-help-new/young-people/health-and-education/mental-health>.

7 Pia van de Zandt and Tristan Webb, Profiling the 50 highest users of legal aid services (NSW Legal Aid, 2013).

8 Alison Wallace et al, Literature Review on Meeting the Psychological and Emotional Wellbeing Needs of Children and Young People: Models of Effective Practice in Educational Settings (Urbis, 2011).

9 Wallace et al, above n 8, 45.

10 Australian Bureau of Statistics, Causes of Death, Australia, 2012, Catalogue Number 3303.0 (2014), table 1.3, line 40. At http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/detailspage/3303.02012?opendocument (viewed 11 April 2014).

11 Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Australian hospital statistics 2011-12, National tables for external causes of injury or poisoning (part 1), Catalogue Number HSE 134 (2013), tables 3 and 4. At http://www.aihw.gov.au/publication-detail/?id=60129543133&tab=3 (viewed 11 April 2014).

12 Kids Helpline, 2012 Overview: Issues Concerning Children and Young People (2013), p 55. At http://www.kidshelp.com.au/grownups/news-research/research-reports/kids-helpline-overview.php (viewed 11 April 2014).