Community arrangements asylum seekers, refugees + stateless persons

Community arrangements for asylum seekers, refugees and stateless persons

Observations from visits conducted by the Australian Human Rights Commission from December 2011 to May 2012

- Back to Contents

- 1 Summary

- 2 Recommendations

- 3 Introduction

- 4 Australia’s mandatory detention and excision regime

- 5 Community arrangements for asylum seekers, refugees and stateless persons

- 6 Some barriers to use of community arrangements

- 7 Closed detention

7 Closed detention

Internal fences, Villawood Immigration Detention Centre.

7.1 The impact of prolonged detention in closed immigration detention facilities

“I used to think, when I was in Iran, that I could handle prison here for 10 years. But it has its own psychological pressures.”

“No one wants to be a refugee. Everyone needs freedom. Why do they keep us like this?”

“Our pain is something else. We have not come here to eat good food or use the internet.”

“You might see things happening; see changes. But I don’t. This is my life, this is my whole world.”

“In Australia, if you have a pet, you take your pet out at least once a week. I haven’t had an excursion in the two years I’ve been in detention ... I don’t even know what Australians look like.”

“Imagine you were in a hotel room and you couldn’t get out. How would you feel? It doesn’t matter what the facilities are like. You just want to get out.”

“Too many people die in detention. No one can give any answer, why these people lose their life for nothing.”

“I have escaped from force and power and pressure in the Iranian system. I cannot accept that I would be out of favour here, with the Australian system. That is very painful.”

As noted above, the Commission has adopted a new approach to its detention visiting activities. The Commission will continue to conduct short visits to detention sites with a focus on specific issues, but is no longer able to undertake detailed monitoring and reporting of conditions of immigration detention.

The Commission visited Villawood IDC, Sydney IRH, Maribyrnong IDC and Melbourne ITA in April 2012.[105] In keeping with the new approach, detailed monitoring of conditions of detention of the kind undertaken in recent years was not conducted during these visits. Instead, the Commission focussed on the situation of people who face prolonged and indefinite detention in closed facilities, including refugees who have received adverse security assessments; refugees who are of interest to or have been charged by the APF; and stateless persons who have not been recognised as refugees. While the human rights and wellbeing of all people in immigration detention are of concern to the Commission, the plight of people who face little or no prospect of release from closed detention in the foreseeable future is of particularly serious concern.

The Commission heard resoundingly of the distress, frustration, anxiety and despair caused by people’s ongoing and indefinite detention. For many people with whom the Commission met, this has been compounded by witnessing so many others move out of closed detention in relatively short timeframes, because they have either been granted permanent protection visas or moved into community placement under the Australian Government’s expansion of community arrangements for asylum seekers and refugees.

Most people the Commission met with in closed facilities were at pains to convey that the conditions of detention were of little import to them. Rather, it was the prolonged and indefinite nature of their detention which was causing people distress: the fact of remaining in closed detention, separated from friends, family and other support networks, for prolonged periods of time, in some cases with little or no prospect of release.

These visits to closed detention facilities once again reinforced the Commission’s long-held concerns about Australia’s system of mandatory, indefinite immigration detention.

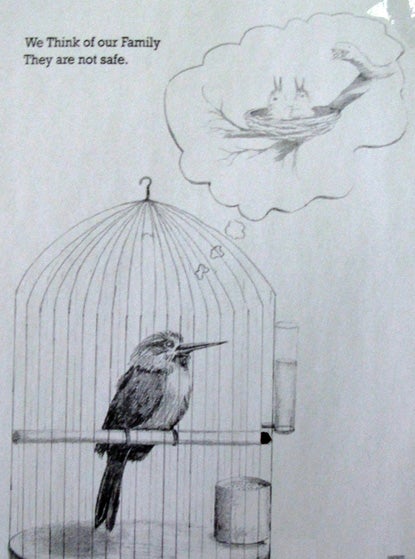

Artwork on the bedroom door of a man in detention, Maribyrnong Immigration Detention Centre.

7.2 Observations relating to closed immigration detention facilities

Notwithstanding the Commission’s new approach to detention visits, some observations about conditions of detention were made during the most recent round of visits. Conditions of detention and the services provided to people who are detained remain important given the range of international human rights standards relating to people deprived of their liberty.[106]

The Commission was pleased to observe a number of positive developments at immigration detention facilities in Sydney and Melbourne, some of which are representative of changes which have been made across the immigration detention network. However, Commission staff also noted a number of areas in which further improvement is needed. The most significant of these are outlined below.

The Commission last visited Villawood for detention monitoring purposes in February 2011. Following this visit, a detailed report was issued containing findings and recommendations to which DIAC provided a public response.[107] Many of the Commission’s observations from its most recent round of detention visits relate to progress made against the findings and recommendations of its 2011 Villawood report.

(a) Health and mental health service provision

Outside makeshift clinic, Villawood Immigration Detention Centre.

In its 2011 Villawood report, the Commission made a series of recommendations relating to physical and mental health services. These included that:

- DIAC consider increasing IHMS staffing levels

- the clinical governance framework for the delivery of mental health services to detainees across the immigration detention network be overhauled such that it is overseen by a consultant psychiatrist with whom ultimate responsibility lies

- active outreach work be extended into accommodation areas across the detention network

- DIAC require at least a minimal IHMS presence at Villawood IDC 24 hours per day, seven days per week

- DIAC require at least a minimal onsite IHMS presence at Sydney IRH.[108]

Clinic, Melbourne Immigration Transit Accommodation.

The most recent visit to immigration detention facilities in Sydney and Melbourne revealed a number of positive developments in the area of health and mental health care many of which the Commission understands have been applied across the detention network. These include:

- An overhaul of the clinical governance framework for the delivery of mental health services at Villawood IDC and across the detention network, involving the appointment of a psychiatrist to oversee mental health service delivery and provide clinical supervision. At all facilities visited, the Commission received positive feedback from IHMS and other staff regarding the leadership of and changes introduced by the new clinical director.

- A comprehensive revision of all IHMS clinical policies, which have been submitted to DIAC for consideration, within the context of contract negotiations.

- The intention that clinical outreach activities will commence within Villawood IDC once staff numbers and Serco escort arrangements have been confirmed, and the recent commencement of mental health group work sessions which the Commission was told are being well received.

- Measures which have been taken to make IHMS services routinely available to people being held at Sydney IRH, and the intention for a more established presence is envisaged there shortly, with the construction of an onsite clinic.

- Increases to IHMS’s physical and mental health staff hours at Villawood which have been made since the Commission’s last visit, and a submission that has been made to DIAC for a further staffing increase (although the round-the-clock IHMS presence recommended by the Commission appears not to be under consideration).

Consultation room, clinic, Melbourne Immigration Transit Accommodation.

(b) Mitigation of suicide and self-harm

The Commission made a series of recommendations towards mitigating the risk of self-harm and suicide among people in detention in its 2011 Villawood report. These included that DIAC ensure that a safety audit be conducted across Villawood IDC and all other detention facilities, and that all appropriate measures be taken to minimise the risk of suicide and self-harm.[109]

It appears that a safety audit has not been conducted at any of the sites visited by the Commission, nor a tool developed for the purpose of conducting such audits across the detention network.

The Commission continues to call for safety audits to be conducted and appropriate measures taken to mitigate the potential for further self-harm, suicide attempts and suicide in immigration detention facilities. Such measures should be taken urgently. Since the time of the Commission’s visit to Villawood in February 2011, there have been a further four deaths in immigration detention, two of which occurred at Villawood and three of which appear to have been suicides.

(c) Staff interactions with people in detention

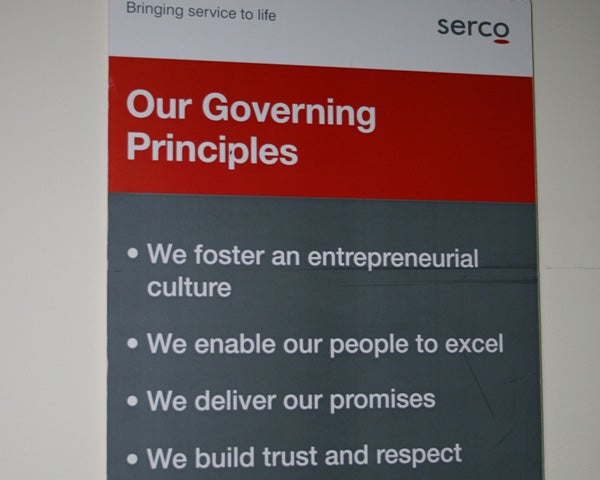

Serco poster, Maribyrnong Immigration Detention Centre.

On previous visits to immigration detention facilities, and in some detention monitoring reports, the Commission has made observations about the interactions between staff and people in detention.[110] During its recent visits, the Commission was struck by the dedication to their work and concern for detainees exhibited by the majority of detention staff with whom it met.

The interagency management teams at Sydney and Melbourne, comprising officers from DIAC, Serco and IHMS, appeared to have strong rapports, respectful professional relationships and an appreciation of the challenges of each other’s roles. Several members of operations and case management staff were commended by their colleagues to the Commission as approachable and effective.

While some people in detention who met with the Commission raised concerns regarding their treatment by staff, many of those who exhibited most distress made a point of noting that they felt that they had been treated with compassion and respect by local management and case management staff.

This feedback resonated with the ways in which many DIAC, IHMS and Serco staff spoke of their concerns regarding the circumstances of people in detention. It appeared that some staff were deeply affected by the often traumatic nature of their work, including responding to suicides and other acts of self-harm. The Commission observed positive signs of peer support, but held concerns for the welfare of some staff.

Some Serco officers with a background in welfare, rather than security, have recently been employed to work with people in detention at Melbourne ITA and Sydney IRH. The introduction of this new welfare-oriented approach to working with detainees was raised as a positive development by staff across agencies working in these facilities. The Commission witnessed positive interactions between welfare-orientated Serco staff and some of the most vulnerable people being held in immigration detention. The Commission welcomes the introduction of this approach and encourages its expansion.

The Commission was pleased to learn that the former policy of case management disengagement in client protest situations, including acts of self-harm such as voluntary starvation, has been nuanced to afford local operations managers a degree of discretion in deciding whether to intervene. On previous detention visits the Commission observed the negative effects of the policy of disengagement, including increased risks to staff safety and potential aggravation of self-harm. The Commission heard from local operations and case management staff that their early intervention in self-harm and other protest actions will often allow them to de-escalate situations by attempting to resolve concerns and convey their interest in securing client wellbeing within the scope of established parameters.

(d) Redevelopment, capital works and infrastructure

Left: kitchen, Banksia unit, Villawood Immigration Detention Centre; right: old accommodation quarters, Melbroune Immigration Transit Accommodation.

In its 2011 report on immigration detention at Villawood, the Commission recommended that the redevelopment of Villawood IDC should be undertaken as soon as possible. The Commission also recommended that:

- the redevelopment include the demolition of Blaxland, the most high-security compound at Villawood IDC

- DIAC ensure that people are detained in the least restrictive form of detention possible at the facility

- the infrastructure concerns raised by the Commission in its 2008 Immigration detention report be addressed in the redevelopment process.[111]

The Commission welcomed various aspects of both completed and planned works at Villawood observed during its most recent visit. These include:

- The significantly improved physical environment of the Banksia unit, including incorporation of a women-specific observation area and self-catering facilities.

- The planned use of far less evident security features in the redevelopment; and assurances that all detainees will be provided lockable personal storage space and access to kitchenettes.

- Advice that consideration is being given to minimising or ceasing use of the loudspeaker system for personal paging in the new development, with reliance instead upon personal notifications by officers to be stationed in each accommodation area.

The Commission was concerned to learn that it is still proposed to use Blaxland in its current form until the final stage of the redevelopment. There are clearly considerable logistical and other challenges associated with the implementation of a major, multi-year redevelopment of a site which remains in constant use. Nevertheless, it remains the Commission’s view that, given the harshness of the physical environment at Blaxland, people held in that compound should be the first to be moved to redeveloped spaces at Villawood, or be transferred to other facilities if that is not feasible and if they are not eligible for community placement.

With respect to infrastructure, the Commission welcomes the new development at Melbourne ITA, which offers a far more benign environment than exists in many other immigration detention facilities. Commission staff were struck, however, by the notable distinction between the new and old sections of Melbourne ITA. In particular, the main accommodation quarters, which house highly vulnerable long-term detainees, have a bleak and dilapidated appearance which is starkly at odds with the new visitor, recreation and administrative areas. The Commission encourages consideration of measures that could be taken to upgrade the main accommodation quarters at Melbourne ITA.

At Sydney IRH, staff spoke highly of the recently constructed visits and recreation area and hoped that it might generate a sense of community within the facility. However, the people in detention with whom the Commission spoke were distressed by the change of policy to visiting arrangements which accompanied its opening. Previously, people were able to receive visitors in the outdoor garage attached to their residence. For most this had already felt like a difficult arrangement, as they wished to be able to host family and friends within their residence. Under the new arrangements, visitors must be received in the visits area, a more institutional, less personalised space which affords no privacy. Several detainees at Sydney IRH told Commission staff that they felt affronted by the change of policy, which appeared to them to be punitive and culturally insensitive.

Left: construction works, Villawood Immigration Detention Centre; right: new visits area, Melbourne Immigration Transit Accommodation.

Despite the range of positive developments which have been made or are proposed in relation to health care service provision in detention, the current clinical spaces at Melbourne ITA, Maribyrnong IDC and Villawood IDC appear entirely inadequate. At Villawood IDC, IHMS staff have been working out of extremely constrained quarters since the destruction of their former clinic during last year’s riots. Staff at this site did, however, appear satisfied that the clinics which are close to completion at both Villawood IDC and Sydney IRH will provide functional settings for their work. The Commission heard numerous concerns about the clinical facilities at Melbourne ITA and Maribyrnong IDC, including that there are serious spatial constraints, in terms of both therapeutic and administrative areas; that clinical and interview spaces are used in multi-purpose capacities to which they are not suited; and that there is a lack of effective soundproofing. Despite these concerns, it appears that provisions have not been made for the expansion and upgrading of clinical facilities in the capital works program at Melbourne ITA and Maribyrnong IDC.

(e) Restrictive places of detention

Left: downstairs, Murray unit – restrictive place of detention used for behavioural management; right: enclosed courtyard, Maygar annexe, Melbourne Immigration Transit Accommodation.

In its 2011 Villawood report, the Commission recommended that DIAC develop a written policy setting out the decision-making process, criteria and rationale for placing a person in the Blaxland annexe, the most restrictive part of the highest security compound at Villawood IDC. The Commission also recommended that the annexe not be used for managing people who have been involved in violent or aggressive behaviour at the same time as it is being used to monitor people who have been placed on observation because they are at risk of suicide or self-harm.[112]

In response to this recommendation, DIAC advised the Commission that its then draft ‘Safe use of more restrictive detention’ policy would be reviewed by the Detention Health Advisory Group Mental Health Sub-Group, and would assist in guiding decisions in relation to the placement of people in restrictive places of detention across the immigration detention network, including the Blaxland annexe.[113]

Disappointingly, it appears that a written policy on the use of Blaxland annexe has not been developed. During the Commission’s most recent visit, staff at Villawood advised that they had not recent co-located in the annexe people who have been involved in aggressive behaviour with people who are deemed to be at risk of suicide or self-harm. However, this practice does not appear to have been ruled out.

Further, the Commission has not been able to obtain a copy of the ‘Safe use of more restrictive detention’ policy, in draft or final form, nor has the Commission been able to establish whether it has ever been used. It is not clear whether any standard written guidance exists for the use of annexes and observation rooms across the network other than the three for which First Assistant Secretary level approval is required on a daily basis – that is, the Murray Unit in Villawood IDC, Zone C in Maribrynong IDC and the Support Unit in Christmas Island IDC.

External telephones, Villawood Immigration Detention Centre.

In previous reports of visits to immigration detention sites, the Commission has raised concerns about the policy which prohibits people who have arrived by boat seeking asylum from having mobile telephones in detention facilities.[114] This policy does not apply to other groups of people in detention.

DIAC’s mobile phone policy can restrict access to communication between people in detention and their family members and support networks; limit the extent to which asylum seekers can hold private telephone conversations with legal representatives or migration agents; and cause tensions between different groups in detention. It also unnecessarily adds to the difficulties associated with people in the community attempting to contact asylum seekers in detention. Further, it can place additional pressure on sometimes inadequate communications infrastructure in detention, by increasing demand for landline telephones.

During the Commission’s most recent visits, the policy of permitting access to mobile phones only to those people in detention who did not arrive by boat remained a source of distress and consternation. Across facilities, people who were denied mobile phones told the Commission that the policy felt punitive. Further, staff and management raised serious concerns about the operational challenges which they face in implementing a two-track approach.

It remains the Commission’s view that there has not been a reasonable justification provided for this policy and it should be reconsidered.

[105] See note 4.

[106] See United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners (1955), at http://www2.ohchr.org/english/law/treatmentprisoners.htm (viewed 10 July 2012); United Nations Body of Principles for the Protection of All Persons under Any Form of Detention or Imprisonment (1988), at http://www2.ohchr.org/english/law/bodyprinciples.htm (viewed 10 July 2012); United Nations Rules for the Protection of Juveniles Deprived of their Liberty (1990), at http://www2.ohchr.org/english/law/res45_113.htm (viewed 10 July 2012); United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, UNHCR Revised Guidelines on Applicable Criteria and Standards Relating to the Detention of Asylum Seekers (1999), at www.unhcr.org.au/pdfs/detentionguidelines.pdf (viewed 7 July 2012).

[107] 2011 Immigration detention at Villawood, note 24; Department of Immigration and Citizenship, Response to the Australian Human Rights Commission Statement on Immigration Detention in Villawood (2011), at http://humanrights.gov.au/human_rights/immigration/idc2011_villawood_response.html (viewed 10 July 2012).

[108] 2011 Immigration detention at Villawood, note 24,Recommendation 10.

[109] 2011 Immigration detention at Villawood, note 24, Recommendation 11.

[110] See, for example, 2010 Immigration detention on Christmas Island, note 63, section 18; 2011 Immigration detention at Curtin, note 24, section 9.6.

[111] 2011 Immigration detention at Villawood, note 24, Recommendation 7. See also Australian Human Rights Commission, Submission to the Parliamentary Committee on Public Works on the proposed redevelopment of the Villawood Immigration Detention Facility (2008), at http://www.humanrights.gov.au/legal/submissions/2009/20090918_villawood_immigration.html (viewed 10 July 2012).

[112] 2011 Immigration detention at Villawood, note 24, Recommendation 8.

[113] See Response to the Australian Human Rights Commission Statement on Immigration Detention in Villawood, note 107, p 6.

[114] See 2010 Immigration detention in Darwin, note 73, section 10; 2011 Immigration detention at Villawood, note 24, section 15; 2011 Immigration detention at Curtin, note 24, section 15.