13 Continuing impacts on children once released

- 13.1 How are children faring once released?

- 13.2 Continuing impacts of detention on infants and preschoolers

- 13.3 Continuing impacts of detention on primary school aged children

- 13.4 Continuing impacts of detention on teenagers

- 13.5 Ongoing impacts of long term detention

- 13.6 Findings regarding the continuing impacts of detention

Both my children are nervous. They were scared of everything in detention. They are still nervous, still scared of everything. The welfare checks really affected their mental health.

(Mother of 5 year old child and 16 year old child, Community Interview, Adelaide, 13 May 2014)

Drawing by primary school aged girl, Christmas Island, 2014.

This chapter contains the responses of children and parents to questions about the impacts of detention on their lives after they had been released into the Australian community. Commission staff conducted interviews with 104 former detainees between April and August 2014.

Children and parents reported improvements in their mood and behaviours once released from the detention environment. However, a significant number reported ongoing negative and emotional impacts of detention.

The respondents to the Inquiry interviews were people waiting to have their refugee cases assessed and were either living in Community Detention arrangements in Australia, or living in private housing on a Bridging Visa E.

There were 1,560 children living in Community Detention arrangements in Australia in August 2014. There were 2,006 children living in the community on a Bridging Visa E in August 2014.[606]

The Inquiry team interviewed 92 children and 12 parents now living in the community. On average, the children who were interviewed had previously been held in detention for 11 months.[607]

The interviewees had been living in the community for varying periods. Chart 54 shows the length of time they had been out of detention.

Chart 54: Length of time children had been out of detention

| Time out of detention | Number of Children |

|---|---|

| 0 - 3 months | 8 |

| 4 - 6 months | 5 |

| 7 - 9 months | 13 |

| 10 - 12 months | 20 |

| 13 - 15 months | 14 |

| 16 - 18 months | 7 |

| 19 - 21 months | 2 |

| 22 - 24 months | 2 |

Australian Human Rights Commission, Based on data from Inquiry Questionnaire for Children and Parents Released from Detention, Australia, 2014, 71 respondents

Twenty-three of the child interviewees were from Afghanistan; 22 were from Iran; 16 were from Sri Lanka; eight were from Iraq; eight were stateless; seven were from Pakistan; three were from Lebanon; two were from Burma/Myanmar, and the remaining three did not specify their country of origin.

The Commission found it difficult to secure interviews with people who had previously been in detention. They reported that they feared negative consequences from the Australian Government if they were found to have spoken to the Inquiry team. Some feared being sent back to detention. One unaccompanied child told the Inquiry about his reluctance to talk in these terms:

I am in Community Detention and have code of behaviour ... and will be sent back into detention ... Detention has made me more afraid of detention. I lost the feeling of being a human being. Do I have the right to be annoyed? What, how can I talk to an Australian guy who is in his country, who can report me to the police and send me back to detention?

(Unaccompanied child, 17 years old, Community Interview, Sydney, 5 August 2014)

13.1 How are children faring once released?

My eldest daughter has phobias and stomach pain from detention. She’s frightened when she sees people being angry or aggressive. My youngest daughter still doesn’t sleep well, she wakes 2 or 3 times a night.

(Mother of 10 year old child, 6 year old child and 4 year old child, Community Interview, Melbourne, 5 May 2014)

The impacts of detention can persist long after the child has left the detention environment. Mental health experts report that closed detention has ‘undeniable immediate and long-term mental health impacts on asylum-seeking children and families’.[608] Child psychiatrists who work with children after their release have reported that recovery can occur in some cases, but that in others, mental health effects may be prolonged.[609]

As part of the Inquiry questionnaire, children and parents were asked if their emotional and mental health had been negatively affected when in detention. Seventy-six percent of respondents answered yes, 15 percent answered no, six percent answered sometimes and three percent said that they were not sure.[610]

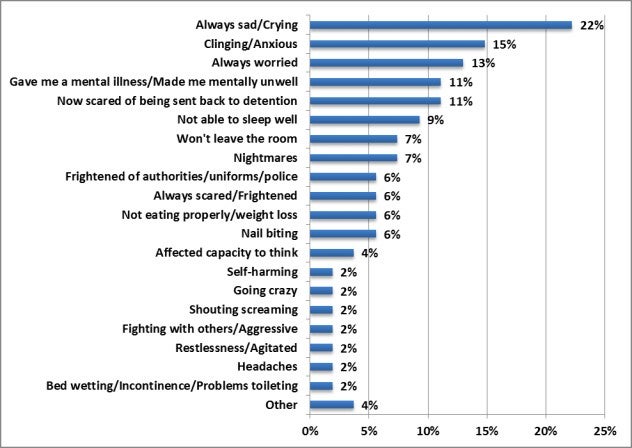

When asked to describe the emotional impacts, children and parents gave the responses at Chart 55.

Chart 55: Reponses of children and parents released from detention to the question: What were the emotional and mental health impacts on you/your children when in detention?

Chart 55 description: Reponses of children and parents released from detention to the question: What were the emotional and mental health impacts on you/your children when in detention? Always sad/crying 22%, Clinging/anxious 15%, Always worried 13%, Gave me a mental illness/made me mentally unwell 11%, Now scared of being sent back to detention 11%, Not able to sleep well 9%, Won't leave the room 7%, Nightmares 7%, Frightened of authorities/uniforms/police 6%, Always scared/frightened 6%, Not eating properly/weight loss 6%, Nail biting 6%, Affected capacity to think 4%, Self-harming 2%, Going crazy 2%, Shouting/screaming 2%, Fighting with others/aggressive 2%, Restlessness/agitated 2%, Headaches 2%, Bed wetting/incontinence/problems toileting 2%, Other 4%.

Australian Human Rights Commission, Inquiry Questionnaire for Children and Parents Released from Detention, Australia, 2014, 75 respondents (Note: respondents can provide multiple responses)

Children and their parents were asked if it was difficult to talk about their time in detention. Forty-four percent of respondents reported difficulties in talking about detention.[611] Of those who reported difficulties, 87 percent said that they ‘didn’t want to talk about it’; that they ‘couldn’t talk about it’; that it was ‘too hard’; that they were ‘scared to talk about it’; or that it ‘reminded them of detention’.[612]

Thirty-nine percent of respondents told the Inquiry team that after release from detention they needed help for emotional problems as shown in Chart 56.

Chart 56: Responses of children and parents released from detention to the question: Since out of detention, have you/your children needed help for emotional problems?

Chart 56 description: Responses of children and parents released from detention to the question: Since out of detention, have you/your children needed help for emotional problems? Yes 39%, No 56%. Sometimes 5%.

Australian Human Rights Commission, Inquiry Questionnaire for Children and Parents Released from Detention, Australia 2014, 77 respondents

Despite the ongoing difficulties after detention, children and their parents reported improvements and progress since being in the community.

When asked whether the behaviour of the child had changed since being released from detention, 70 percent said yes.[613] An overwhelming majority (89 percent) of respondents said that there had been an improvement in the behaviour of the child once released as shown in Chart 57.

Chart 57: Responses of children and parents released from detention to the question: Did you/your children show any changes in behaviour once released from detention?

Chart 57 description: Responses of children and parents released from detention to the question: Did you/your children show any changes in behaviour once released from detention? Iimproved 89%, Problems from detention remain 8%, Declined 3%.

Australian Human Rights Commission, Inquiry Questionnaire for Children and Parents Released from Detention, Australia, 2014, 64 respondents

When asked whether the child was meeting development milestones (including reading and writing), 62 percent of respondents answered yes, 33 percent said sometimes, three percent said no, and two percent were unsure.[614] A majority (66 percent) reported that the child did not have any difficulties playing and getting along with other children since being out of detention.[615] When asked whether the child needed behavioural assistance at school, 81 percent answered no, 16 percent said yes, and three percent said sometimes.[616]

13.2 Continuing impacts of detention on infants and preschoolers

The Inquiry team spoke with the parents of 14 children who were aged 4 years or under while in detention. Parents of four of the children reported that they thought that detention had an impact on the development of their child’s ability to talk and to bond.[617]

According to a Professor of Developmental Psychiatry, the 0 to 4 age group is particularly vulnerable to damage in detention:

The group I’m particularly concerned about are the very young. We saw some children who were born in detention, in the first round of detention, who spent the first 3 to 4 years of their lives in these sorts of environments, witnessing major trauma, who developed attachment difficulties, who continue to have problems in their overall level of functioning related to that. ...

I think this is absolutely a significant concern, and we know that those sorts of experiences in early childhood and infancy are much more likely to lead to long term poor outcome and mental health and developmental problems.[618]

Some parents expressed their concern about the impacts of detention on their young children. These concerns included developmental problems, evident in children who had spent comparatively short periods in detention.

A father of a child who spent two months in detention as a 10 month old infant, told the Inquiry:

At 2 years old, my daughter can’t talk. Her speech development has been affected. The doctor has said the trauma of detention has affected her speech, which will be delayed ...

My child is so scared she can’t play with other children. She can’t play with her own baby sister. She weeps at noise. She still wakes up at 12.00 am – every night at 12 she starts weeping ... in detention she would wake up at 12 screaming, the head count would terrify her.

(Parent of 2 year old child, Community Interview, conducted by phone, 12 June 2014)

Another parent told the Inquiry that her daughter:

wakes 3 times in the night. She now sleeps with her father because she is very frightened of the police ... . She can’t believe that she is free. She thinks if she does something wrong, she will go back to detention.

(Mother of 3 year old child, Community Interview, conducted by phone, 12 June 2014)

Some parents reported that their children were frightened as a result of detention. One parent told Inquiry staff that her child, detained at age 4 on Christmas Island:

has great fears today and can’t tell the difference between in or outside detention. She is still not confident. She’s frightened that the police will take her.

(Parent of 5 year old child, Community Interview, Darwin, 15 April 2014)

Her daughter now needs ‘constant attention’ from her mother, as she is:

too trusting, she wants to go with everyone, she would ask people in the park outside ‘can you take me home?’ I can’t work because I need to look after her full time she is terrified and needs a lot of attention. She has problems with making friends.

(Parent of 5 year old child, Community Interview, Darwin, 15 April 2014)

13.3 Continuing impacts of detention on primary school aged children

Before my children go to bed, I have to put them in nappies. When they are walking around and a police car goes by they feel scared, they don’t feel safe.

(Father of 6 and 7 year old children, Community Interview, Sydney, 16 April 2014)

The Inquiry interviewed 20 children who were aged between 5 and 12 years when in detention. Interviewees reported that the development of some of these children had been impaired and that they required ongoing support. One mother reported that her child had spent three months on Christmas Island and had witnessed violent incidents. She told Inquiry staff:

My 6 year old child is in kindergarten rather than school. Her development was affected so much that she cannot keep up with other children. But she has received treatment to help her with play and for aggressive, angry behaviour.

(Mother of 7 year old child, 6 year old child and 2 year old child, Community Interview, Melbourne, 5 May 2014)

The mother explained that her daughter had been receiving support from a psychiatrist and occupational therapist since her release from detention.

Another mother described her 5 year old boy as being scared and traumatised:

My little one is still scared of everybody. He saw a psychologist while in detention but he is still scared and traumatised, we don’t know what to do and how to help.

(Mother of 5 year old child, Community Interview, Adelaide, 13 May 2014)

13.4 Continuing impacts of detention on teenagers

The detention centre made us lose confidence in ourselves. We cannot trust anybody.

(17 year old unaccompanied child, Community Interview, Sydney, 5 August 2014)

The Inquiry team interviewed 56 children who were aged between 13 and 17 during the time they spent in detention. Thirty-one of these children were unaccompanied.

When the teenagers were asked whether they thought that their emotional or mental health was negatively affected by the experience of detention, 72 percent responded yes, five percent thought sometimes, 19 percent answered no, and four percent were unsure.[619]

When asked on the day of the interviews how often they felt sad, the teenagers who were now living in the community provided the responses at Chart 58.

Chart 58: Responses by teenagers released from detention to the question: How often do you feel sad?

Chart 58 description: Responses by teenagers released from detention to the question: How often do you feel sad? All of the time 8%, Most of the time 15%, Some of the time 63%, A little of the time 10%, None of the time 4%.

Australian Human Rights Commission, Inquiry Questionnaire for Children and Parents Released from Detention, Australia 2014, 48 respondents

When asked how often they felt happy, the teenagers who were now living in the community provided the responses at Chart 59.

Chart 59: Responses by teenagers released from detention to the question: How often do you feel happy?

Chart 59 description: Responses by teenagers released from detention to the question: How often do you feel happy? All of the time 4%, Most of the time 36%, Some of the time 43%, A little of the time 15%, None of the time 2%.

Australian Human Rights Commission, Inquiry Questionnaire for Children and Parents Released from Detention, Australia 2014, 47 respondents

At the first public hearing, the Commission heard evidence from the Principal of Holroyd High School, in Sydney. The Principal spoke about the large population of asylum seeker children at the school and their academic performance after release from detention.

The restrictions and the institutionalisation that happens in the detention centres make them quite generally passive, depressed, slow to react when they come out of detention. What we notice is that a lot of them have difficulty with concentration, with focusing on their school work, no matter how keen they are to get back into it, and with memory. Some of the students actually have memory loss. They’re not recalling things which they should recall.[620]

Teenagers reported to Inquiry staff that detention had affected their sense of identity and worth in the community.

I have definitely started looking at myself from the perspective of convincing others in the community ... I am not a criminal ... I am worth what others are.

(17 year old unaccompanied child, Community Interview, Sydney, 5 August 2014)

I am still scared of police in the community, because in detention I always felt like I did something wrong.

(16 year old child, Community Interview, Adelaide, 13 May 2014)

When I came out of detention I felt very nervous. It was hard to deal with normal people.

(16 year old unaccompanied child, Community Interview, Sydney, 5 August 2014)

Teenagers reported that detention affects their ability to trust or to feel trustworthy:

I still have difficulties in trusting people, I only have one friend.

(17 year old unaccompanied child, Community Interview, Sydney, 5 August 2014)

I am not sure what people’s real motives are.

(16 year old unaccompanied child, Community Interview, Sydney, 5 August 2014)

I am scared people won’t trust me if they know I have been in detention.

(16 year old unaccompanied child, Community Interview, Sydney, 5 August 2014)

At the first public hearing, a former detainee, Bashir Youssoufi, spoke about the impacts on his study and his ability to concentrate at school after leaving detention. Bashir was 14 years old when he arrived in Australia and was detained for almost a year on Christmas Island.

I do think about those days and I had a mental problem with those days that I spent in detention centre ... at the beginning when I was in the detention centre I was studying, learning English and later on ... I wasn’t able to memorise things and I couldn’t concentrate properly and I can’t remember things like things my friend told me do this and after two seconds I forgot everything. I still I do carry those impacts.[621]

13.5 Ongoing impacts of long term detention

This Inquiry is not the first work that the Commission has done with people after they have left detention. From December 2011 to May 2012 the Commission conducted a series of visits and interviews with asylum seekers, including families with children and unaccompanied children.[622] The Commission documented the impacts of detention in a 2012 report:

The effects of prolonged, indefinite immigration detention on the wellbeing of people who have experienced detention do not dissipate immediately upon a person’s release. Most of the refugees and asylum seekers in community placement with whom the Commission spoke told staff of their experiences of detention and the legacy of such experiences in their everyday lives. Some people spoke of invasive memories which interrupted their sleep and affected their appetite. Others spoke of disturbing dreams. Still others told the Commission that they had problems with their memory, concentration and ability to learn, all of which they attributed to the effects of being held in closed detention.[623]

From those interviews the Commission observed that the longer the person had spent in detention, the more likely they were to be affected by detention after their release. The Commission reported that:

People’s recovery appeared especially pronounced when they had spent shorter periods of time in detention facilities. Those who had spent prolonged periods in detention prior to their community placement reported that they continued to be powerfully affected by difficult past experiences.[624]

In a submission to the Inquiry, the Royal Australasian College of Physicians noted their concern about ‘the long-term impact of detention on children’. The submission noted that the ‘psychological distress resulting from detention can persist for years after release’.[625]

Clinicians from the Children’s Hospital at Westmead Refugee Clinic also reported evidence of trauma and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in children exiting detention:

We have seen a very large number of children who have been in detention centres. More than half of all the asylum seeker children we are currently seeing are suffering from post-traumatic stress ... A number of children have been deeply traumatised by their time in detention resulting in post-traumatic stress disorder, nightmares and self-harming.[626]

In evidence to the second public hearing of the Inquiry, Professor Louise Newman reported that she is currently treating adults who she met as children in detention in the period 2000 to 2005.

I treat several people who I first met during the first round of detention as children, who have ongoing post traumatic symptoms and preoccupations, who are finding it difficult to make a positive adjustment to life in the community. So some [with] very classical symptoms of having nightmares memories and recollections of things that happened to them that still remain troubling. Some have quite marked depression. Now it might be that there are other factors contributing to that but we are not sure.[627]

Professor Newman reported correlations between the experience of detention and poor outcomes for children:

...when we look at life time prevalence of disorder and we look at the contribution of the fact of detention, we found there to be a direct relationship between the experience of detention and children’s poor outcome.[628]

At the first public hearing of the Inquiry, Associate Professor of Paediatrics, Karen Zwi reported on the potential for long term mental health impacts on children as a consequence of their detention.

I’m seriously concerned about the long term impact as we’ve heard this morning and as I know from my own patients from 10 years ago. People who have suffered a degree of trauma in their own country and come by boat have high expectations, and then sit in a state of limbo with no hope and no sense of future, experience damage as a result of that and these children have been through that process. I think many of them will have ongoing mental health issues like anxiety, post-traumatic stress of some description. They may well have developmental delay. I think it’s very hard to address that after the fact.[629]

13.6 Findings regarding the continuing impacts of detention

While children show noticeable improvements in social and emotional wellbeing once released from detention, significant numbers of children experience negative and ongoing emotional impacts after prolonged detention.

The Commission makes the general finding in chapter 4 (supported by the evidence in chapters 4 and 6 to 11) that the mandatory and prolonged detention of children breaches Australia’s obligation under article 24(1) of the Convention on the Rights of the Child because of the impact of prolonged detention on the mental health of people detained.

The Committee on the Rights of the Child has stressed that the Convention requires States to provide effective remedies to redress violations of the rights in the Convention, and that:

Where rights are found to have been breached, there should be appropriate reparation, including compensation, and, where needed, measures to promote physical and psychological recovery, rehabilitation and reintegration... (General Comment No 5, paragraph 24).

Accordingly, the Commonwealth is under an obligation under article 24(1) of the Convention to provide medical and associated support services to promote the physical and psychological recovery, rehabilitation and reintegration of children who have had their mental health affected by their time in detention. This is the basis for the Commission’s recommendation that government-funded mental health support be provided not only to children currently in detention, but also to those who have previously been detained at any time since 1992.

[606]Department of Immigration and Border Protection, Immigration Detention and Community Statistics Summary: 31 August 2014 (2014), p 3. At http://www.immi.gov.au/managing-australias-borders/detention/_pdf/immigration-detention-statistics-august2014.pdf (viewed 17 September 2014).

[607]Australian Human Rights Commission, Inquiry Questionnaire for Children and Parents Released from Detention, Australia, 2014, Responses to question: How long did you spend in Locked Detention?, 81 responses.

[608]M Dudley, Z Steel, S Mares, L Newman ‘Children and young people in immigration detention’ (2012) 25(4) Current Opinion in Psychiatry 285, p 290.

[609]L Newman, ‘Seeking Asylum - Trauma, Mental Health and Human Rights: An Australian Perspective’ (2013) 14(2) Journal of Trauma & Dissociation 213, p 218; M Dudley, Z Steel, S Mares, L Newman ‘Children and young people in immigration detention’ (2012) 25(4) Current Opinion in Psychiatry 285, p 287.

[610]Australian Human Rights Commission, Inquiry Questionnaire for Children and Parents Released from Detention, Australia, 2014, Responses to question: Do you think the emotional and mental health of you/your children was negatively affected when in detention?, 89 respondents.

[611] Australian Human Rights Commission, Inquiry Questionnaire for Children and Parents Released from Detention, Australia, 2014, Responses to question: Since out of detention, do you have difficulties telling people about detention? 77 respondents.

[612]Australian Human Rights Commission, Inquiry Questionnaire for Children and Parents Released from Detention, Australia, 2014, Responses to question: Since out of detention, do you/your child have difficulties telling people about the experience of detention?, 39 responses.

[613]Australian Human Rights Commission, Inquiry Questionnaire for Children and Parents Released from Detention, Australia, 2014, Responses to question: Did you/your children show any changes in behaviour once released from Locked Detention?, 77 respondents.

[614]Australian Human Rights Commission, Inquiry Questionnaire for Children and Parents Released from Detention, Australia, 2014, Responses to question: Now that you’re out of detention are you/your child keeping up with developmental milestones?, 60 respondents.

[615]Australian Human Rights Commission, Inquiry Questionnaire for Children and Parents Released from Detention, Australia, 2014, Responses to question: Since out of detention do you/your child have difficulties playing and getting along with other children?, 76 respondents.

[616] Australian Human Rights Commission, Inquiry Questionnaire for Children and Parents Released from Detention, Australia, 2014, Response to question: Since being out of detention, have you/your children needed help for behaviour at school?, 64 respondents.

[617]Australian Human Rights Commission, Inquiry Questionnaire for Children and Parents Released from Detention, Australia, 2014, Responses to question: Did locked detention have an impact on your child’s development, including speaking, crawling, walking and bonding?, 6 responses, and responses to, toddler development - explanations, 5 responses.

[618]Professor L Newman, Second Public Hearing of the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014, Melbourne, 2 July 2014. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-Inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014-1(viewed 11 September 2014).

[619]Australian Human Rights Commission, Inquiry Questionnaire for Children and Parents Released from Detention, Australia, 2014, Responses to question: Do you think your emotional and mental health was negatively affected by the experience of Locked Detention?, 53 respondents.

[620]Mrs D Hoddinott, First Public Hearing of the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014, Sydney, 4 April 2014. At https://www.humanrights.gov.au/sites/default/files/Ms%20Hoddinott.pdf (viewed 18 September 2014).

[621]B Yousoufi, First Public Hearing of the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention, Sydney, 4 April 2014. At https://www.humanrights.gov.au/sites/default/files/Mr%20Yousufi.doc (viewed 8 September 2014).

[622]Australian Human Rights Commission, Community arrangements for asylum seekers, refugees and stateless persons: Observations from visits conducted by the Australian Human Rights Commission from December 2011 to May 2012 (2012), section 5.3. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/publications/community-arrangements-asylum-seekers-refugees-and-stateless-persons#Heading260 (viewed 17 September 2014).

[623]Australian Human Rights Commission, Community arrangements for asylum seekers, refugees and stateless persons: Observations from visits conducted by the Australian Human Rights Commission from December 2011 to May 2012 (2012), section 5.3. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/publications/community-arrangements-asylum-seekers-refugees-and-stateless-persons#Heading260 (viewed 17 September 2014).

[624]Australian Human Rights Commission, Community arrangements for asylum seekers, refugees and stateless persons: Observations from visits conducted by the Australian Human Rights Commission from December 2011 to May 2012 (2012), section 5.3. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/publications/community-arrangements-asylum-seekers-refugees-and-stateless-persons#Heading260 (viewed 17 September 2014).

[625]Royal Australasian College of Physicians, Submission No 103 to the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014 p 4. At https://www.humanrights.gov.au/sites/default/files/Submission%20No%2010… (viewed September 4 2014).

[626]Children’s Hospital at Westmead Refugee Clinic, Submission No 1 to the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014 p 1. At https://www.humanrights.gov.au/sites/default/files/Submission%20No%201%20-%20Children%27s%20Hospital%20at%20Westmead%20Refugee%20Clinic_0.doc (viewed September 14 2014).

[627]Professor L Newman, Second Public Hearing of the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention, Melbourne, 2 July 2014. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-Inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014-1(viewed 11 September 2014).

[628]Professor L Newman, Second Public Hearing of the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention, Melbourne, 2 July 2014. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-Inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014-1(viewed 11 September 2014).

[629]Associate Professor K Zwi, First Public Hearing of the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention, Sydney, 4 April 2014. p 7. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-Inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014-1(viewed 8 September 2014).