Chapter 2: Constitutional reform: Creating a nation for all of us - Social Justice Report 2010

Social Justice Report 2010

Chapter 2: Constitutional reform: Creating a nation for all of us

- 2.1 Introduction

- 2.2 Why does Australia as a nation need to recognise Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in the Constitution?

- 2.3 What could reform look like?

- 2.4 What are the next steps to a successful referendum?

- 2.5 Conclusion

2.1 Introduction

A century ago, the Australian people engaged in a debate about creating a nation. They held meetings...They wrote articles and letters in newspapers. Many views were canvassed and voices were heard. The separate colonies, having divided up the land between them, discussed ways of sharing powers in order to achieve a vision of a united Australia. The result was the Australian Constitution, establishing the Commonwealth of Australia in 1901.

A century ago our Constitution was drafted in the spirit of terra nullius. Land was divided, power was shared, structures were established, on the illusion of vacant land. When Aboriginal people showed up – which they inevitably did – they had to be subjugated, incarcerated or eradicated: to keep the myth of terra nullius alive.

A century after the original constitutional debate we have an opportunity to remake our Constitution to recognise and accommodate the prior ownership of the continent by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.[1]

One hundred and ten years ago years ago, Queen Victoria gave Royal Assent to the Australian Constitution, the founding document of our nation and pre-eminent source of law in the country.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples were noticeably absent from its drafting.

We were excluded from the discussions concerning the creation of a new nation to be situated on our ancestral lands and territories.

We were expressly discriminated against in the text of the Constitution, with provisions that prevented us from being counted as among the numbers of the new nation, and which prevented the new Australian Government from making laws that were specifically directed towards us.[2]

As a consequence, the Constitution did not – and still does not – make adequate provision for us. It has completely failed to protect our inherent rights as the first peoples of this country.

Former Chief Justice of the High Court of Australia, Sir Anthony Mason, has referred to this as a ‘glaring omission’.[4]

In the face of this history of exclusion, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have consistently and vehemently fought to have our rights recognised and acknowledged by the Australian Government and the Australian people. In 1938, two great Aboriginal warriors stated that:

You are the New Australians, but we are Old Australians. We have in our arteries the blood of the Original Australians; we have lived in this land for many thousands of years. You came here only recently, and you took our land away from us by force.[6]

There is a long history of Indigenous and non-Indigenous people calling for this recognition including:

- 1938 – Aborigines Conference

- 1967 – Referendum and preceding campaigns

- 1988 – Barunga Statement

- 1988 – Constitution Commission’s Report

- 1995 – Social Justice Package submissions[5]

- 1999 – Referendum on the preamble of the Constitution

- 2000 – Council for Aboriginal Reconciliation Report

- 2008 – 2020 Summit

- 2008 – Social Justice Report

- 2009 – Australian Human Rights Commission Submission to the National Human Rights Consultation.

These examples illustrate years of advocacy for constitutional recognition.

Since the days of the Bark Petition, Aboriginal people have been aware that the protection offered by legislation – ranging from the Aboriginal protection ordinances to the Land Rights Act – is only as secure as the government of the day...We have long believed that the protection of our rights deserves a higher level of recognition and protection.[3]

It is upon this historical foundation that Australians are increasingly accepting the need to address this non-recognition and exclusion through constitutional reform.

The determination of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander leaders to fight to secure our future in this nation has resulted in some improvements in the recognition of our land, cultural and social rights. This has been reflected in advancements such as:

- the fight of Eddie Mabo and others for the native title rights of the Mer people, that led to the High Court decision of Mabo (No 2)[7] and the legislative response, the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth)

- the work of people such as Lowitja O’Donohue, Les Malezer, Mick Dodson, Megan Davis and Tom Calma in the development of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (Declaration)[8] and its subsequent endorsement by the Australian Government.

I believe the nation is beginning to come to terms with its true, complete history. This requires the nation, to come to terms with a history of exclusion and the violations of the rights of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

A major step in this journey was the 1967 referendum that resulted in a critical change that allowed Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to be counted in the census. It also gave the Australian Government the power to make laws for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

Ten years ago, the Council for Aboriginal Reconciliation identified constitutional reform as unfinished business of the reconciliation agenda, calling for the Commonwealth Parliament to prepare legislation for a referendum.[9]

The most recent highpoint came in 2008, when the Prime Minister, delivered the National Apology to Australia’s Indigenous Peoples (National Apology) for the forcible removal of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples from their lands and their families.[10]

There have been some further recent positive developments with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples being formally recognised in several state constitutions:

- The Queensland Constitutional Convention, held in June 1999, recommended that the Constitutions of each state should recognise the custodianship of the land by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.[11] Queensland’s Constitution was formally changed in 2010.[12]

- In 2004, Victoria became the first state to recognise the Aboriginal people of Victoria in their Constitution in 2004.[13]

- In 2010, the New South Wales (NSW) Parliament passed legislation to recognise Aboriginal peoples in the NSW Constitution.[14]

This recognition provides a good basis on which to build the necessary consensus within the Australian community that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples should be acknowledged in the nation’s foundational legal instrument.

At the federal level, bipartisan support for amending the Constitution in this regard has been maintained since 2007.[15] Bipartisan support was reaffirmed by both major parties as election commitments in the federal election held in August 2010.[16]

In this Chapter, I build on these current developments and commitments. I seek to answer three key questions that will go to the heart of a successful campaign:

- Why is there a need for constitutional reform to recognise Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples?

- What could reform look like?

- What are the next steps?

In section 2 of this Chapter I discuss the need for and significance of constitutional reform. I focus on the symbolic and practical effects on the lives of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, as well as the benefit this could bring to all Australians.

Section 3 outlines some of the possibilities for reform. It is my belief that the nation is ready to move beyond preambular recognition to address the provisions of our Constitution that permit and anticipate racial discrimination.

Section 4 analyses historical lessons and contemporary practicalities to chart some of the essential next steps to be taken, toward achieving a successful referendum.

We have reached a critical juncture. Australians have a rare opportunity to stand together as one people, united in recognition of the contribution of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples to this land and this nation, in the past, the present and into the future. What is at stake is an inclusive national identity and a path towards a truly reconciled nation.

History shows that constitutional reform is not easy. As with the 1967 referendum, it will require the open hearts and minds of the majority of Australians in order to succeed.

I believe now is the right time to take up this challenge: for Australia to come together as a nation, as in 1967, to build the consensus and momentum to make this reform a reality.

2.2 Why does Australia as a nation need to recognise Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in the Constitution?

The Constitution demarcates the powers of each of our three branches of governance – the Parliament, the Executive and the Courts.

The current Chief Justice of the High Court of Australia, Chief Justice Robert French has said, ‘the Constitution creates the space in which all other domestic laws operate in this country. It defines the extent of [Australia’s] legal universe’.[17]

As highlighted in Chapter 1 of this Report, I am convinced that building positive relationships based on trust and mutual respect between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and the broader Australian community is critical to overcoming Indigenous disadvantage. I believe that constitutional reform is necessary to facilitate the building of these positive relationships.

(a) Achieving true equality for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples

Achieving true equality does not mean that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples should be assimilated or integrated into the nation’s governance and society. The Declaration in its second preambular paragraph affirms:

that indigenous peoples are equal to all other peoples, while recognizing the right of all peoples to be different, to consider themselves different, and to be respected as such.[18]

Affirming the principles of equality, non-discrimination and the right to be different would celebrate and respect our diversity and our culture as an integral part of the life of the nation.

In July 2010, I voiced my support for constitutional reform to recognise Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and our rights.[19] A number of questions were raised in response. Most of these questions went to the impact that constitutional change could have on the lives of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. I believe that there are a number of significant outcomes for us as a result of constitutional reform. I will specifically address:

- the symbolic value of constitutional reform that leads to practical outcomes

- the value of constitutional reform in contributing to greater protection of the rights of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

I will explain each of these below.

(i) Symbolic value leading to practical effect

Over the years, there has been plenty of debate about the value of symbolism versus practical action.[20] I do not believe that these are mutually exclusive, nor do I believe they should be framed as an ‘either/or’ option. Why can’t we do both?

Symbols are an important part of building nations. They are reminders of a collective past and provide guidance towards an aspirational collective future. They are the things upon which practical actions should be built.

The Australian flag, the national anthem, and the green and gold colours of national sporting teams, are all symbols that connect Australians to the nation’s identity and inspire feelings about that identity.

Recognition is particularly important for the psyche of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Academic Waleed Aly recently commented on the positive impact of symbolic recognition of Indigenous peoples through the welcome and acknowledgement of country protocols:

... I'm frankly astounded to hear lots of non-Indigenous people talk about what is and is not tokenistic on an issue like this, when so much of what happened to the Indigenous population has deep symbolic resonance. It's not just that they were deprived materially. It's not just lack of education. It's not just lack of economic opportunity, although those things are extremely important. It is also the denial of the humanity that comes with that and unless you've experience that... I think its extraordinarily difficult to say just how profoundly important that [recognition] can be... I don't know, I'm a bit disturbed to hear so many people prepared just to dismiss it, when it's not their experience to have.[21]

A senior Aboriginal activist (name not provided for cultural reasons) spoke of the personal impact achieved by the 1967 referendum:

At the time I definitely thought that the [1967] Referendum achieved something – personally, it made me lose my inferiority complex... It made me prouder to proclaim my Aboriginality.[22]

Formal recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples within the Australian Constitution would surely strengthen this sentiment as expressed by this senior Aboriginal man.

The positive effects of symbolic recognition extend beyond Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples to all Australians. As noted by Professor Larissa Behrendt:

Symbolic recognition that could alter the way Australians see their history will also affect their views on the kind of society they would like to become. It would alter the symbols and sentiments Australians use to express their identity and ideals. It would change the context in which debates about Indigenous issues and rights take place. It would alter the way the relationship between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australia is conceptualised. These shifts will begin to permeate them. In this way, the long term effects of symbolic recognition could be quite substantial.[23]

The power of symbols is that they can inspire action. This in turn can result in positive practical effects that lead to an improved quality of life for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

The most obvious example of an event that has achieved significant symbolic value is the National Apology.[24] On that day, Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians sat, held each other and cried together. The nation took a great leap forward towards reconciling with its past. Prior to the National Apology, many argued that an apology would be purely symbolic, and that focus should be confined to pursuing ‘practical reconciliation’.

Text Box 2.1: The National Apology

The National Apology was a national recognition of the effects of government policies that dispossessed and dispersed Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples across the country. While there are people who were directly affected by these policies, all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have been and continue to be affected in some way.

Symbolic value

The National Apology empowered the Stolen Generations members by acknowledging their experience and life struggle as a result of government laws and policies. Beyond the Stolen Generations, it was a moment for all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to seize. Many felt for the first time that they belonged – that we were finally acknowledged as part of the nation.

In addition, it also had a positive impact for non-Indigenous Australians, particularly how it affected their relationship with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. The National Apology has enabled a wider understanding and appreciation of the historical wrongs that had occurred, and was a necessary and positive step forward to advance reconciliation.

Practical effect

In the political context, the National Apology has become a significant point of reference. It has been referred to in parliamentary debates[25] and reports.[26]

The National Apology has also subsequently informed government policies and programs. This has most visibly manifested in the establishment of the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Healing Foundation and reinvigorated discussion about options for reparations for the Stolen Generations.

In the legal context, Justice Kirby considered the impact of the National Apology on legislative interpretation in the High Court’s Blue Mud Bay decision. Justice Kirby acknowledged that the National Apology had bipartisan support and it

reflects an unusual and virtually unprecedented parliamentary initiative, it does not, as such, have normative legal operation...Yet it is not legally irrelevant to the task presently in hand. It constitutes part of the factual matrix or background against which the legislation in issue in this appeal should now be considered and interpreted. It is an element of the social context in which such laws are to be understood and applied, where that is relevant. Honeyed words, empty of any practical consequences, reflect neither the language, the purpose, nor the spirit of the National Apology.[27]

Those who argue against symbolic actions miss the fundamental linkage between the symbolic and the practical. Actions that have real and lasting effect on a community are both symbolic and practical.

I strongly believe that reforms to the Constitution to recognise Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and our rights will provide significant symbolic value as well as have a profound practical effect.

This will of course depend on the extent of the reform, a point discussed in greater detail later in this Chapter. How governments and the broader Australian community respond to those reforms will also be critical to realising their full potential.

In summary, symbolic recognition has the potential to:

- address a history of exclusion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in the life of the nation

- improve the sense of self worth and social and emotional well-being of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples both as individuals, communities and as part of the national identity[28]

- change the context in which debates about the challenges faced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities take place

- improve the relationships between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians.

(ii) Will there be greater protection for the rights of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples?

It is occasionally argued that constitutional reform to recognise Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples will result in more rights for one specific group of people within the nation.[29]

I believe this view is misconceived.

It fails to acknowledge the reality of our existing societies with their own polities and legal systems prior to colonisation. It fails to reflect the subsequent discrimination towards and the denial of the rights of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

It also fails to recognise that the historic non-recognition of our peoples’ rights has continuing negative impacts today.

There are parallels between the need for a Declaration recognising the rights of Indigenous peoples and the need for constitutional reform.

Text Box 2.2: Why we need an Indigenous Declaration

James Anaya, the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights and fundamental freedoms of indigenous people

By particularizing the rights of indigenous peoples, the Declaration seeks to accomplish what should have been accomplished without it: the application of universal human rights principles in a way that appreciates not just the humanity of indigenous individuals but that also values the bonds of community they form...

It is precisely because the human rights of indigenous groups have been denied, with disregard for their character as peoples, that there is a need for the Declaration. In other words...the Declaration exists because indigenous peoples have been denied equality, self-determination, and related human rights. It does not create for them new substantive rights that others do not enjoy. Rather, it recognizes for them rights that they should have enjoyed all along as part of the human family, contextualizes those rights in light of their particular characteristics and circumstances, and promotes measures to remedy the rights’ historical and systemic violation...

There should not have to be a Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, because it should not be needed. But it is needed. The history of oppression against indigenous peoples cannot be erased, but the dark shadow that history has continued to cast can and should be lightened. The Declaration is needed for the difference it can and will make for the future...[30]

Reform to the Constitution will address this position of entrenched disadvantage and exclusion, rather than affording Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ additional rights. Professor Pat Dodson, one of the leaders of reconciliation, has aptly stated that this is a matter of ‘justice, not special benefit’.[31]

Recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in the nation’s foundational document will redress a history of exclusion, and have the concrete impact of recognising us as Australia’s indigenous peoples within the nation’s governance.

One of the fundamental rights that most Australians take for granted is the right to live free from discrimination. However, the Constitution currently offers no protection of this right. While recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples can be accommodated through inserting a new preamble into the Constitution, change to the body of the Constitution will be required to ensure protection against discrimination.

Aboriginal lawyer and academic Megan Davis observes that:

In Australia, Indigenous interests have been accommodated in the most temporary way, by statute. What the state gives, the state can take away, as has happened with the ATSIC, the Racial Discrimination Act and native title.[32]

Relying on the benevolence of parliament to protect the rights and interests of all Australians does not provide adequate protection against discrimination.[33]

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are particularly vulnerable to this lack of protection. The Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth) (RDA) has been compromised on three occasions: each time it has involved Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander issues.

There is no clearer evidence of this discriminatory effect, than the Northern Territory Emergency Response (NTER) that affects 73 remote Indigenous communities in the Northern Territory.

The NTER in its original application was not subject to the RDA – the federal legislation designed to ensure equality of treatment of all people regardless of their race. The RDA as an Act of Parliament can be disregarded simply through the passage of further legislation. The Constitution as it currently stands did not prevent the suspension of the RDA. Therefore, it was ineffective in protecting our peoples from the most fundamental of all freedoms, the freedom from discrimination.[34]

In order to address this inadequacy and the historical denial of justice, substantive constitutional change is necessary to improve the protection of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ rights against discrimination.

(b) Achieving a unified nation within Australia

With the National Apology the nation has been given a wonderful opportunity to begin to make justice possible not only for the Aboriginal people but for all the people of this nation. Justice denied one group within the nation is a diminishment of us all and the nation will remain diminished until the wrong is righted.[35]

Recognising Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and our rights will positively benefit all Australians. It will:

- enrich the identity of the nation

- improve the effectiveness of the nation’s democracy through increasing the protection of the rights of all Australians

- make significant headway towards a reconciled Australia.

(i) Enriching the nation’s identity

In the National Apology the Prime Minister honoured and acknowledged Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the ‘the oldest continuing cultures in human history’.[36] This is not simply a matter of our identity as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples; it also informs the nation’s identity. Former Prime Minister Paul Keating articulated this in his famous Redfern Speech in 1992.

Text Box 2.3: The Redfern Address: Prime Minister Paul Keating

It is a test of our self-knowledge.

Of how well we know the land we live in. How well we know our history.

How well we recognise the fact that, complex as our contemporary identity is, it cannot be separate from Aboriginal Australia.

The message should be that there is nothing to fear or to lose in the recognition of historical truth, or the extension of social justice, or the deepening of Australian social democracy to include Indigenous Australians.

We cannot imagine that the descendants of people whose genius and resilience maintained a culture here through fifty thousand years or more, through cataclysmic changes to the climate and environment, and who then survived two centuries of dispossession and abuse, will be denied their place in the modern Australian nation.[37]

Constitutional expert, Professor George Williams argues that ‘the story of our nation is incomplete without the histories of the peoples who inhabited the continent before white settlement’.[38] In fact it has been argued that in failing to acknowledge the prior presence of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, the current Constitution works to perpetuate the myth of terra nullius (no man’s land).[39]

When the British arrived they treated the land no known as Australia as ‘no man’s land’. This characterisation was justified because the ‘indigenous inhabitants were regarded as barbarous or unsettled and without law’.[40] The historic High Court decision on Mabo swept away the historical myth of terra nullius. The High Court decided:

The fiction by which the rights and interests of indigenous inhabitants in land were treated as non-existent was justified by a policy which has no place in the contemporary law of this country.[41]

However, despite the advances made by the Mabo (No 2) decision, the Constitution continues to overlook the prior presence of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and societies.

Recognising Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ within the Constitution will enrich the nation’s identity, making it an inclusive one that reflects both the ‘old’ and the ‘new’ Australians.

(ii) Improving the effectiveness of our democracy: Protecting the human rights of the Australian Community

Keating’s Redfern Address described the test of extending care, dignity and hope to the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples of Australia as the fundamental attributes of Australia’s reputation as a first rate social democracy.

Text Box 2.4: The Redfern Address: Prime Minister Paul Keating

[I]n truth, we cannot confidently say that we have succeeded as we would like to have succeeded if we have not managed to extend opportunity and care, dignity and hope to the indigenous people of Australia - the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island people.

This is a fundamental test of our social goals and our national will: our ability to say to ourselves and the rest of the world that Australia is a first rate social democracy, that we are what we should be – truly the land of the fair go and the better chance.[42]

Unfortunately, as noted by George Williams, Australia

holds the dubious distinction of being perhaps the only country in the world whose Constitution still contains a ‘races power’ [section 51(xxvi)] that allows the Parliament to enact racially discriminatory laws.[43]

Section 25 of the Constitution also contemplates the exclusion of voters based on race. It was aptly described by the 1988 Constitutional Convention as ‘odious’.[44] It has no place in a modern democracy. This provision reflects that for decades after Federation, Australian states denied Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples voting rights.[45] The potential for people to be disqualified from voting extends to all races and is not limited to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. This provision, that contemplates discrimination on the basis of race, has not been amended or remedied.[46]

George Williams points out that Australia’s Constitution was drafted against a backdrop of racism that led to the White Australia policy and a range of other discriminatory laws and practices.[47]

The drafters of the Constitution were men of their time. Their thinking was influenced by the ‘political and social imperatives’ of the day.[48]

Australia has long since progressed from the views of this time in other important ways – for example women’s suffrage was achieved in the early years of the new Federation (when all women were entitled to vote) and the White Australia policy was ended in the early 1970s.

So why does this historical backdrop continue to inform our contemporary legal landscape in relation to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples?

The proposed referendum provides an opportunity to address this fundamental flaw in the Constitution, which is incompatible with an effective social democracy.

The Social Justice Report 2008 argued that while constitutional change cannot be a panacea for everything, it is about ensuring that the ‘founding document sets out the ambitions and expectations for all Australians’.[49] It argues that the Constitution should ‘reflect a modern, twenty first century Australia by providing a legal foundation for reconciliation, where human rights are respected at all levels of government’.[50]

The absence of human rights protections, particularly protection against discrimination, from the Constitution does not only affect Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. This affects all Australians.

(iii) Headway towards a reconciled nation

Inaugural Co-Chair of the National Congress of Australia’s First Peoples (National Congress), Sam Jeffries believes that:

To create a meaningful and lasting partnership, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders must be part of the Constitution - the document that defines the nation’s soul.

I have confidence that there is goodwill in the community to see this type of practical reconciliation accomplished.

The Congress sees reform as a necessity to underpin a new relationship with all Australians. This is fundamental to build a just and modern Australia.[51]

The acknowledgement of the existence of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as a unique element of the nation is something of which all Australians can be proud.

Achieving a successful referendum will not be easy and it will require a united effort. Australians will need to walk together and talk together in order to achieve reform to the Constitution so that it truly reflects the heart and soul of the nation. In this way the process of undertaking a campaign for constitutional recognition can itself have a reconciling effect.

Larissa Behrendt has noted that throughout Australia’s history there have been a number of significant moments when Australians have stood up and spoken out in support of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.[52] The 1967 referendum was one such moment. More recently there was the Reconciliation March in the year 2000, and the National Apology in 2008. If it were possible to harness such historic moments of support, constitutional reform to recognise Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples would be more than a mere possibility. Professor Mick Dodson has also professed his belief in the capacity of the Australian population to embrace our recognition:

... [T]he capacity to embrace the past honestly, and acknowledge its truths, goes to the very depths of our national identity and what we stand for as peoples. We must rid ourselves of this psychological cloak of darkness before it becomes our shroud.

...

It’s not a big ask.

It’s something that Australians are eminently capable of doing.[53]

I agree with Larissa Behrendt and Mick Dodson. Constitutional reform is something Australians are ready for.

By its very nature, the Constitution is an instrument of the people. It is the people who have the power to change or amend it. Through this reform process, the nation will be able to decide how it wants its first peoples positioned in the nation and what sort of protections it wants to assure for all its citizens.

I am confident that the nation can agree on a reform process that maximises benefits for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, for the broader Australian community and for the nation.

2.3 What could reform look like?

To ensure this destination is reached, the nation needs to know what reform could look like. It is essential that the proposal put to the Australian people is sound and sensible.[54] This requires informed debate about the various possibilities for reform.

The proposed reform should be underpinned by a real commitment to:

- improve the lives of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples

- ensure adequate protection of the human rights of all Australians

- ensure a solid foundation upon which to build a reconciled nation.

A reform proposal grounded in these commitments is something that I believe Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and the broader Australian public can relate to and support.

The extent of reform could be limited to inserting a new preamble that recognises Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the first peoples of Australia and our unique place in the history and future of the nation. Alternatively, the opportunity could be taken to the next level and address issues within the body of the Constitution.

Early discussions about the extent of reform indicated a narrow focus on ‘[only] options for recognising Indigenous people in the preamble to the Constitution’.[55]

While this appears to be the position of some, the majority of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people that I have canvassed constitutional reform with hope to achieve broader reform that addresses the discriminatory provisions within the Constitution.

Megan Davis and Dylan Lino observe that there are a number of key possibilities for reform within the existing provisions of the Constitution, some of which have been proposed over the years including:

- inserting a new preamble recognising Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples

- amending the races power (s 51 (xxvi)) – either total repeal or amendment so that it can only be used for beneficial purposes

- the deletion of s 25, which contemplates electoral disqualification on the basis of race

- dedicated parliamentary seats for Indigenous people

- the entrenchment of a treaty or a treaty-making power

- the protection of Indigenous-specific rights, such as rights to lands and territories

- guarantees of equality and non-discrimination

- changes to how federalism impacts on Indigenous people

- the move to an Australian republic.[56]

Megan Davis, in her role as Director of the Indigenous Law Centre based in the Faculty of Law at the University of New South Wales, heads a research project on constitutional reform and Indigenous peoples. This project is currently considering these possibilities. [57]

Decisions on the extent of reform will require significant, detailed and informed debate. As public representatives, parliamentarians at all levels and across all persuasions, must be informed by the view of the broader Australian community, garnered through public education campaigns and consultations.

(a) Preambular reform

The preamble for the Australian Constitution is contained within the Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act 1900 (Imp), the Act of the British Parliament that established the Australian Commonwealth. As such it precedes the Constitution, and is not formally part of the Constitution itself.

There is legal uncertainty as to whether the existing preamble can be altered by referendum pursuant to s 128 of the Constitution. As a result, the 1999 referendum proposed to insert a new preamble at the beginning of the Constitution, rather than to amend the preamble at the head of the Australia Constitution Act 1900 (Imp).[58]

Despite not being formally part of the Constitution, the existing preamble

can be legitimately consulted for the purpose of solving an ambiguity or fixing the connotation of words which may possibly have more than one meaning....[b]ut the preamble cannot either restrict or extend the legislative words, when the language is plain and not open to doubt, either as to its meaning or scope.[59]

The existing preamble’s focus is on the federation of Australia. It includes the following elements:

- the agreement of the people of Australia

- their reliance on the blessing of Almighty God

- the purpose to unite

- the character of the union - indissoluble

- the form of the union - a Federal Commonwealth

- the dependence of the union - under the Crown

- the government of the union - under the Constitution

- the expediency of provision for admission of other colonies as States.[60]

A significant amount of work has already been progressed in suggesting appropriate alternative wording for a new preamble. As outlined below, one of the key lessons to be learned from the 1999 referendum on the preamble is the importance of full and proper consultation with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples on the form of recognition.

It is my view that, in order to be meaningful, the recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in a new preamble should include acknowledgment:

- of our historical sovereignty, stewardship, ownership and custodianship prior to colonisation

- that we are the oldest living cultures in the world and that the Australian nation is committed to preserving and revitalising our cultures

- that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as traditional owners, custodians and stewards continue to make a unique and significant contribution to the life of the nation

- that our cultures, identities and connections to our lands and territories continue.

(b) Reform to the body of the Constitution

It would be unwise to prematurely confine this debate on constitutional reform to preambular recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Mick Dodson has suggested that:

The three key international principles of human rights I would like to see entrenched in our Constitution are the principles of equality, non-discrimination and the prohibition of racial discrimination.[61]

I believe considerations for more substantive reform should address the provisions within the body of the Constitution that permit, enable or anticipate racial discrimination – namely ss 25 and 51(xxvi).

The races power (s 51(xxvi)) enables the Parliament to make ‘special laws’ with regard to such groups. The problem is that the Constitution does not stipulate that these ‘special laws’ or policies should benefit those affected, as opposed to discriminating against them.[62]

On this basis, the current Chief Justice of the High Court has noted that the races power is still not satisfactory despite the changes to it from the 1967 referendum:

The intention of the [1967] amendment was entirely beneficial. That however did not turn the power generally into a beneficial one. The weight of High Court authority supports the view that s 51(xxvi) authorises both beneficial and adverse laws. It can properly be described as a constitutional chimera.[63]

Section 51(xxvi) is applicable to all races within the Australian community. For this reason, all Australians are not protected from being discriminated against on the basis of their race.

Addressing this situation is, however, complex. My predecessor has warned against focussing on the wording of s 51(xxvi) as providing the solution. A focus on clarifying that this provision can only be used for beneficial purposes could provide ineffective protection. This is because determining what actually constitutes a benefit is essentially a complicated and subjective test:

It is also not difficult to imagine a future situation where a government might pass particular legislation proclaiming that it was intended to improve the welfare and wellbeing of Indigenous peoples [or other races], even though the legislation was contrary to the consent of the peoples.[64]

For this reason, reforms that introduce a broader protection against discrimination may be more effective (as discussed below).

The Social Justice Report 2008 identified the need to reform the body of the text of the Constitution including:

- removing s 25 which anticipates people being disqualified from voting on the basis of their race

- inserting a provision that guarantees, for all Australians, equality before the law and freedom from discrimination – with such a protection drafted in a way that would guide the operation of s 51(xxvi) to ensure that ‘special laws’ for the people of a particular race could not be made if they were discriminatory.[65]

Constitutional reform processes by their nature form an integral part of building a nation’s identity. In the 21st century I think that the majority of Australians would be offended were they to know that their Constitution permits the Commonwealth Parliament to validly enact laws that are racially discriminatory. Or that contemplates that people could be disqualified from voting simply on the basis of their race.

I do not think these provisions reflect what the nation wants in a modern Australia. In fact, quite the opposite.

Most Australians I meet pride themselves on being part of a liberal democratic society that does not condone discrimination or racism. However, it can be inferred from the National Human Rights Consultation that the majority of Australians are probably not aware these provisions are contained in the Constitution.[66]

The presence of these provisions in the nation’s foundational document goes to the core of Australia’s national identity and beliefs. I am a firm believer that if Australians were aware that their Constitution did not protect its citizens from discrimination, the nation would take collective action to bring about reform to enshrine the principles of non-discrimination and equality.

Making changes to the body of the Constitution will require the innovative thinking of constitutional technicians to work through the various opportunities and options for change in order to present clear, considered and developed proposals to the Australian public.

For example, the research project headed by Megan Davis on constitutional reform and Indigenous peoples, highlighted above, is examining a range of reforms to the Constitution. The extent of reform should be informed by the results of the research project and the views of other experts. It should also be informed by the views and voices of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, who have historically been excluded from such processes.

Potential proposals must be capable of being readily communicated to and understood by the Australian public. Persuasive arguments, using plain-English, must be developed to justify why reform will benefit Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and the broader Australian community.

Ensuring the Australian community can effectively participate in the processes leading up to the referendum will require them to be fully informed and educated on these issues. This will be discussed further below.

2.4 What are the next steps to a successful referendum?

The Australian Constitution can only be altered by referendum. Section 128 of the Constitution and the Referendum (Machinery Provisions) Act 1984 (Cth) set out the procedure for amending the Constitution by referendum.

Text Box 2.5: Procedure for amending the Australian Constitution

The key steps to holding a referendum[67]

- The proposed changes to the Constitution are set out in a Bill of Parliament. The Bill must be passed by an absolute majority of both houses of Parliament. Alternatively, if there is disagreement between the houses that has lasted for three months over the proposal, the referendum as originally proposed in either house may proceed.

- The referendum is held between two and six months after the Bill is passed by Parliament.

- A majority of voters nationwide, plus a majority of voters in a majority of States (four out of six) must approve the referendum. This is known as the ‘double majority’.

- After passage by the voters, the proposed alteration to the Constitution requires the Royal Assent.[68]

The referendum process

The Yes/No arguments

Within four weeks after the Bill is passed, a majority of the Parliamentarians who voted for the proposal prepare a ‘Yes’ case (the arguments for making the amendments); and a majority of those who voted against it prepare a ‘No’ case (the arguments for voting against the amendments). If there is unanimous support only a ‘Yes’ case is prepared.

Holding the referendum

After the Bill is passed the Governor-General issues a writ for the referendum.

The polling day, which must be on a Saturday, is set between 33 and 58 days after the issue of the writ.

The Electoral Commissioner must provide every elector on the roll later, at least 14 days before polling day, the following:

- a statement outlining the proposed amendments

- the ‘Yes’ case

- the ‘No’ case (if there is one).

At the referendum electors vote by writing either ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ in the box opposite each question on the ballot paper.

The result of the referendum

If the referendum is supported by a double majority the Governor-General gives the proposed law Royal Assent and the Constitution is altered.

The stringent requirements for ‘double majority’ indicate that the drafters did not intend the Constitution to be easily amended. Nor has it proved to be:

- there have been 44 referendums held since 1901

- only eight of these have been successful

- the last successful referendum was held in 1977

- the last referendum was held in 1999.[69]

Australia’s Constitution ranks as the most difficult in the world to amend.[70] As a consequence, the vast majority of our Constitution remains as originally enacted. It continues to reflect the legacy of being an instrument crafted in an era when racial discrimination was not considered unacceptable.

Despite the apparent difficulty of the task at hand it must be remembered that the original drafters of the Constitution in drafting s 128 (the referendum provision), empowered the people to mould and shape the Constitution to reflect the nature of our current society.[71] It is we the people who can change our Constitution.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have been the subject of three referendums to date (1944, 1967, and 1999), of which only one was successful (1967). The insertion of a new preamble has been the subject of one referendum to date (1999) and it was unsuccessful.

Text Box 2.6: The 1944, 1967 and 1999 referendums

The 1944 referendum[72]

The 1944 referendum sought to give the federal government power over a period of five years, to legislate on a wide variety of matters including the ability to legislate for Indigenous Australians.[73] It obtained majority in two states and only obtained 45.99% of the national vote, and therefore was not carried.[74]

The 1967 referendum

On 27 May 1967, after years of campaigning by numerous Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander leaders and organisations, the nation went to the polls to decide if the Constitution should be amended to:

- give the federal parliament the power to make laws in relation to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people (amending s 51(xxvi))

- allow for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to be included in the census (removing s 127).[75]

The result was an overwhelming 90.77% vote to support the referendum. A majority in all states voted to support the referendum. It is the most successful referendum result in Australian history.[76]

The 1999 referendum

Following much public debate and a Constitutional Convention on whether Australia should become a republic, the nation went to the polls on 6 November 1999. The referendum proposed two amendments to:

The result was a no vote for both amendments. On the question of a republic, 54.87% voted against the proposal and on the question of the preamble 60.7% voted no. In no state did a majority vote yes for either question.[79]

George Williams and David Hume have analysed Australia’s history of referendums and identified some critical factors that are essential for a successful referendum. They include:

- bipartisan support

- popular ownership

- popular education.[80]

While there are lessons to be learnt from all previous referendums, for the purposes of this Chapter, I will use these key factors to compare the stark outcomes of the 1967 and 1999 referendums. Rather than providing a comprehensive historical analysis of these two referendums, I will draw out key lessons that can provide guidance for the proposed referendum.

(a) Bipartisan support

National bipartisan support is essential for the successful passage of any referendum. While it is not a guarantee for success, no referendum has been successful without it. Because of the ‘double majority’ needed, bipartisan support at the state and territory level is also essential.[81]

At the moment bipartisan support for recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in the Constitution has been expressed by the Labor Party, the Coalition and the Greens. The Independents have also expressed their support.

Maintenance of this level of bipartisan support throughout the course of the referendum process will be critical. For instance, if there is no dissent during the passage of the referendum Bill through both houses of parliament, only a ‘Yes’ case needs to be prepared. If this is achieved, a ‘No’ case will not be developed.

(i) The 1967 referendum

The 1967 referendum was preceded by over 30 years of advocacy by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and the broader Australian population. The years of advocacy led to an extended period of national debate. It was this debate that helped generate a climate of consensus. This in turn helped achieve a political consensus that garnered bipartisan support.[82]

The strength of the parliamentary support for the referendum was reflected in the fact that a ‘No case’ was not put to the Australian people.[83]

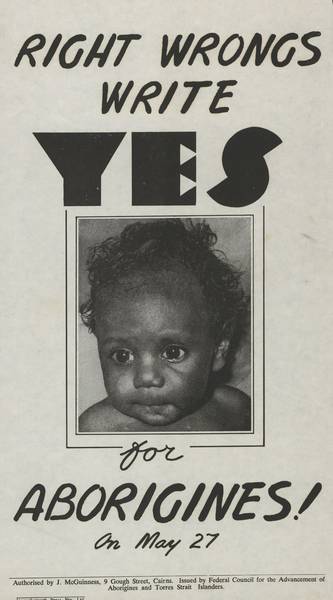

Without a ‘No case’ the message to support the referendum was communicated to the Australian people in a clear and concise way, ‘Vote Yes for the Aborigines’. The pictures and the slogans of the Vote Yes Campaign in the 1967 referendum captured the hearts and minds of Australian people.

Figure 2.1: Pamphlet, 'Right Wrongs Write YES for Aborigines on May 27’[84]

(ii) The 1999 referendum

In direct contrast to the 1967 referendum, the question on the proposed preamble in the 1999 referendum was characterised by political disunity. This politicised the campaign and undermined its chances of success.

The question of inserting a new preamble gained momentum during the Constitutional Convention in 1998, the Australian Government’s formal process of consultation on the issue of whether Australia should become a republic.[85] The Constitutional Convention identified several elements that could be reflected in a new preamble, including recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.[86]

It was during the drafting of the proposed text for the new preamble that the process became politicised. This drafting was undertaken largely by the then Prime Minister, working with poet Les Murray, and was done without bipartisan support.[87] Further differences between the political parties emerged over the proposed wording for the recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

The Opposition pre-empted the Prime Minister’s version with its own preamble. This version was subsequently supported by the Australian Democrats and the Australian Greens. Their version recognised Indigenous Australians as 'the original occupants and custodians of our land'.[88]

The Prime Minister's draft was released for comment on 23 March 1999. He considered it to reflect 'a sense of who we are, a sense of what we believe in, and a sense of what we aspire to achieve in the future'.[89] It only referred to the historical nature of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples connection with the land, and omitted any reference to custodianship:

Since time immemorial our land has been inhabited by Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders, who are honoured for their ancient and continuing cultures.[90]

Almost seven hundred submissions were received on the draft preamble. The response was largely critical of the content of the proposed preamble including the failure to go beyond recognition of prior occupation. In addition to the substance of the proposed preamble, there were objections to the process by which it was drafted.[91]

On 11 August 1999, the final version of the second preamble was released with the introduction in the House of Representatives of the Constitution Alteration (Preamble) Bill 1999.

(iii) Lessons learnt

The contrast between the bipartisan nature of the 1967 referendum and the partisan politics that undermined the 1999 preambular proposal could not be more stark.

It is essential that as this referendum campaign progresses, the current bipartisan support is maintained. Strong and secure bipartisan support from all levels and persuasions of government, as well as the community sector will be critical to success.

With bipartisan support from all of the major political proponents at the Federal level, we have achieved the first major milestone in the journey ahead. If bipartisan support can be maintained and the referendum Bill can pass through Parliament unanimously, we might again be in a position for another campaign with only the ‘Yes Case’. This would be an optimal outcome.

It will also be important to secure bipartisan support at the state and territory levels of governments. As an Australian Government priority, constitutional reform must be placed on the COAG agenda.

(b) Popular ownership

There is often greater support and strength for a proposal that is championed by the people. Proposals that are perceived to be developed for political purposes or written by a minority of people in positions of power are less likely to be seen as relevant to people’s lives, and therefore less likely to garner their support.

It is therefore not surprising that creating opportunities for all Australians to participate in discussion and debates throughout the entire referendum process are necessary. This creates popular ownership in the process. Providing sufficient time and opportunity for comprehensive debate on the issues has been a critical factor in successful referendums. It is important that the referendum is not perceived as owned either by politicians or the elite, but by the nation as a whole.[92]

Widespread involvement by the public must continue through to the development of the proposed amendments.[93]

(i) The 1967 referendum

The success of the 1967 referendum did not happen over night. Nor did it happen in a vacuum. A critical factor in the outcome was the years of campaigning that preceded the vote, by both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as well by members of the broader Australian public.

Many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men and women fought long and painful battles to achieve such a great victory. The battle began well over 30 years before the referendum. Activists such as William Cooper, John Patten (sometimes known as Jack), William (Bill) Ferguson, and Charlie Perkins, Pearl Gibbs and Joyce Clague just to name a few, all played a significant role in the lead up to the 1967 referendum. Others like, Faith Bandler, a South Sea Islander woman, also fought alongside our leaders.

A number of events and organisations influenced and educated the broader Australian community about the conditions that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people were living in and the treatment they were subjected to. These organisations and events played an important role in influencing the decision to hold the referendum, including:

- The bark petitions presented to the Australian Prime Ministers and the Commonwealth Parliament over the years in 1963 (the only one to have been formally recognised), 1968, 1998 and 2008. The bark petitions are considered 'founding documents' of Australian democracy and were a catalyst for a long process of legislative and constitutional reform to recognise the rights of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.[94]

- The establishment of the Australian Aboriginal League (AAL) founded by Yorta Yorta man William Cooper.[95]

- The establishment of the Aboriginal Progressive Association (APA) was led by Fred Maynard, John Patten and William Ferguson. The APA with the AAL declared that ‘Australia Day’ in 1938 – coinciding with the 150th anniversary of the landing of the colonisers – would be a ‘Day of Mourning’.[96]

- The Federal Council for the Advancement of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders (FCAATSI) – formerly the Federal Council of Aboriginal Advancement – was established as an overarching body for the various Aboriginal political organisations emerging in the late 1950s. FCAATSI focused on equal citizenship rights and specific rights for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. As early as 1958 FCAATSI officially decided to push for a referendum.[97]

- Coinciding with the civil rights movement in the United States, students at the University of Sydney formed the Student Action for Aborigines (SAFA) headed by Charlie Perkins. In 1965 SAFA undertook the Freedom Rides – travelling across regional NSW towns drawing public attention to the treatment of Aboriginal people.[98]

- In March 1962 the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1962 (Cth) belatedly provided for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples the right to vote in federal elections. States and territories also amended their laws and by 1965 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people across Australia had the right to vote.[99]

- The Aboriginal Australian Fellowship (AAF) a broad coalition. One of the AAF’s key activities was to campaign for changes to the Constitution.[100]

- The Vote Yes Campaign was launched on 2 April 1957. The campaign was led by Indigenous activists including Pearl Gibbs and Joyce Clague and non-Indigenous activists including Faith Bandler and Lady Jessie Street. The ten year campaign involved rallies and demonstrations across Australia. Support for the referendum began to grow rapidly. Petitions were repeatedly presented to Parliament House.[101]

Finally, after years of advocacy, in February 1967 the Australian Government agreed to hold a referendum on this issue. [102] The preceding campaigns influenced the decision to hold the referendum, and as a consequence there was popular ownership of it. Importantly, this ownership extended to both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and the broader Australian public.

(ii) The 1999 referendum

The Australian Government undertook a formal consultation on the issue of whether Australia should become a republic. The consultation, held in February 1998, was in the form of a Constitutional Convention.

One hundred and fifty-two delegates from all around Australia attended the Convention. The delegates were a combination of elected and appointed delegates.

Seventy-six delegates were appointed by the Australian Government and included parliamentary, community, Indigenous and youth representatives from every state and territory. The other 76 delegates were elected by the Australian voters. Having half of the delegates elected by the Australian population was a means of ensuring the Convention was representative.

A voluntary postal ballot was conducted by the Australian Electoral Commission in late 1997 to elect these delegates. It was the largest national postal ballot ever held in Australia, with the participation of 47% of eligible voters. The 76 elected delegates were chosen from 690 nominated candidates.

The delegates met for 12 days. During this time they examined different models for choosing a republican head of state. The options discussed included by direct election, appointment by a Constitutional Council, and election by Parliament. The delegates also considered issues such as the powers, title and tenure of a new head of state, and proposals for a new preamble to the Australian Constitution.

The government committed to submitting the republican model that emerged from the convention to a referendum to be held before the end of 1999. The Convention supported an in-principle resolution that Australia should become a republic and recommended that the 'bipartisan appointment of the President model' and other related constitutional changes be put to the Australian people at a referendum.[103]

The establishment of the Constitutional Convention was a representative process. However, as the campaign continued, it became more politicised and Australian people felt more isolated from the debates. It is critical that Australian people not only actively participate but feel a sense of ownership of the process.

The politicisation of the process and the focus on the republic itself marginalised the public and diluted and confused messaging about proposed preambular reforms. In the end, the debate about the preamble failed to capture the public’s imagination.[104]

Furthermore, the 1999 preamble proposal also contained several other controversial aspects (that did not relate to recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples), which meant that the proposal was unlikely to obtain sufficient support.[105]

The extent of recognition was also contentious. The Prime Minister’s version of the preamble constrained itself to referring only to past occupation and recognising the ‘continuing cultures’ of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, but as several commentators noted at the time, it did not extend to explicitly recognising land ownership or custodianship prior to settlement.[106] This isolated many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples from supporting the proposed preamble. This was influenced by the lack of consultation with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.[107]

(iii) Lessons learnt

Much of the success of the 1967 referendum was due to the fact that the Vote Yes campaign built upon the momentum already generated by a series of preceding Indigenous rights campaigns. These campaigns were driven by key Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander advocates and organisations who worked together with non-Indigenous advocates for the recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ rights. The widespread consensus generated by extensive national debate over several years was fundamental to its success and contributed to a sense of public investment and ownership.[108]

In contrast the 1999 referendum, despite starting out as a representative process, became a political and elitist process with the Australian population becoming marginalised.

Referendums are the people’s opportunity to change their nation’s governance framework. The public must be front and centre throughout the entire process. The role of politicians is to facilitate and enable this public voice.

Consequently, the active engagement of the Australian public must be sought and achieved. To this end widespread consultation throughout the referendum process is fundamental to its success. There are two aspects of an engagement strategy that will be essential:

- engagement with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples

- engagement with the broader Australian population.

In 1999, the lack of consultation and incorporation of Indigenous views in the draft preamble meant that it was viewed by many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as ‘yet another blow to reconciliation’.[109] Proper engagement with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in the referendum process can itself be a vehicle of reconciliation. In this way, the process of engagement and consultation becomes as important as a positive outcome.

The consultation process will need to be undertaken with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, drawing on their contributions for how best to reflect recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in the Constitution.

In addition to engaging with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples there will need to be extensive engagement with the broader Australian community.

This debate should focus on Australia’s national identity, belonging, and the place of Indigenous peoples in our society to ensure the broadest possible consensus for any proposed constitutional amendment.

As I said in my address to the National Press Club:

Yes, there will be debates, speeches, opinion pieces in the press, people prowling the parliamentary corridors, Constitutional lawyers at 10 paces, yea and nay sayers, documentaries, panel discussions, arguments at dinner parties, barbecues and in front bars – all of these things.

[It is] precisely all of these things that will build awareness, focus minds and hearts and help move us all forward as a nation.[110]

(c) Popular education

The 2009 National Human Rights Consultation highlighted a general lack of knowledge and understanding by the Australian public of the nation’s political and legal system, constitution and referendum processes.[111]

The lack of knowledge was of such an extent that the primary recommendation of the National Human Rights Consultation Committee was that education should be the highest priority for improving and promoting human rights in Australia.[112]

Consequently it is important that comprehensive and accurate information is provided to the public to inform their vote.

Further, past referendums have demonstrated that the greater the understanding among the Australian public of the issues being proposed, the greater the chance the referendum will be supported.[113]

The ‘Yes/No’ booklet often does not suffice to provide the balanced and credible information that is required.[114]

(i) The 1967 referendum

The advocacy that led up to the 1967 referendum was essential in raising awareness of the conditions faced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in Australia at the time. This was an educative function in its own right.

However, a necessary part of any formal education campaign must be clear and concise messaging as to what the referendum is actually proposing to achieve.

The 1967 referendum evidenced the importance of ensuring that the Yes argument is clear and concise. Despite the technical nature of the amendments, it was the clarity of message that mobilised the Australian population in record numbers to vote yes.

There is an inherent tension at play between a clear articulation of the precise legal effect of the referendum and the need for a simple and concise message to garner majority support.

(ii) The 1999 referendum

The 1999 referendum witnessed the establishment of a ‘neutral campaign’ as well as the ‘Yes’ and ‘No’ Committees. The Referendum (Machinery Provision) Act 1984 (Cth) was amended to allow for the ‘Yes’ and ‘No’ Committees to be allocated campaign funds of $7.5 million each and the 'neutral' campaign was allocated a further $4.5 million.[115]

The 39 page ‘Yes/No’ booklet published by the Australian Electoral Commission became the main source of information during the formal campaign.

The information provided in the booklet was drafted by the corresponding members of Parliament who either supported or opposed the amendments. As a consequence, the booklet presented information to the public in a largely polarised manner. This did not necessarily assist in increasing the public’s understanding of the issues in a clear and coherent manner.

Text Box 2.7: The ‘Yes/No’ booklet for the 1999 referendum

The ‘Yes/No’ booklet for the insertion of a new preamble noted the following reasons in support of the preamble.

In summary, a ‘YES’ vote on the preamble for our Constitution would:

- enable the Australian people to highlight the values and aspirations which unite us in support of our Constitution

- contribute importantly to the process of national reconciliation between indigenous and non-indigenous Australians

- recognise at the end of our first century of federation the enduring priorities and influences that uniquely shape Australia’s sense of nationhood.[116]

In contrast the reasons for opposing the insertion of a new preamble provided in the pamphlet included:

- It’s Premature – it is absurd to introduce a new Preamble until we know whether Australia will become a Republic.

- It’s a Rush Job – we should not be tacking these words onto our Constitution without more work and much more public consultation.

- It’s a Politicians’ Preamble – the people haven’t had a say on what should be included in their Preamble.

- It’s Part of a Political Game – while the Labor Party voted against the Preamble in Parliament, they will not campaign against it.

- It’s a Deliberate Diversion – the Preamble is an unnecessary diversion from the most important issue at stake - the Republic model.

- It’s Got Legal Problems – the Preamble referendum question is misleading and there is much debate about what the legal effect of the Preamble will be.

- Its Content is Defective – the proposed Preamble is far more likely to divide rather than unite Australians.[117]

In a review of the machinery of referendums, the Standing Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs noted that the 1999 ‘Yes/No’ booklet provided voters with only the minimum information needed to make an informed decision at a referendum. It was necessary to supplement it with more targeted and contextual information. The Committee recommended that for future referendums, a bipartisan Referendum Panel be appointed for the purposes of promoting and educating voters about the proposed arguments.[118]

In addition to the ‘Yes/No’ booklet, the 1999 referendum campaign included a public education kit for voters.[119] The kit included information on the current system of government, referendum processes, and background information on the referendum questions themselves.[120]

(iii) Lessons learnt

The 1999 referendum had an extensive education campaign that was compromised by polarised messaging.

Like the 1967 referendum, I believe a tension between simplicity of messaging and a clear articulation of what will be the effect of the referendum will arise in the lead-up to the proposed referendum. This tension will need to be discussed, managed and resolved prior to the official launch of the future campaign.

The proposed constitutional amendments should be:

- targeted and accessible

- readily translated into plain English (and other languages)

- able to garner the widespread level of support to be successful.

The public education campaign accompanying a referendum necessarily needs to be broad enough to be a component of the process from its very inception and should extend to the development and drafting of the proposals. All consultation on a proposed referendum topic needs to:

- include a public education component

- explain the Constitution

- explain the legal and political system of Australia

- explain the process of referendums

- explain the impact proposed reforms will have on peoples rights

- identify and address any other specific issue/s at hand.

It is essential that public education campaigns are accessible and appropriate for all elements of the Australian public, in particular, marginalised groups who may not ordinarily have access to such information, or be able to participate in mainstream democratic processes. Information may need to be targeted for specific groups such as Indigenous peoples, women, children and youth, elderly people, culturally and linguistically diverse groups, and people with disabilities. Internet and social networking sites could be utilised to expand the reach and access of the information.

Informing any referendum process with a comprehensive and proper public education program is vital to ensuring that the participation of all Australians, and particularly Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, comes from an informed perspective.

(d) Ensuring a successful referendum strategy

The success of the 1967 referendum reflects over 30 years of advocacy resulting in a clear and concise message calling for reform. It also reflects the high level of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and non-Indigenous involvement in the process leading up to the referendum in 1967.

In contrast, the failure of the 1999 referendum reflects a process that resulted in confused and complicated messaging. It also reflects the fact that despite extensive consultative processes early on in the campaign, the lack of engagement by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and the broader Australian community in the development of the reform proposal fostered a politicised process and ultimately an unsuccessful result.

The lessons learnt from these and other referendums provide significant guidance for developing a successful referendum strategy.

We must learn from past successes and mistakes if we are to progress the proposed referendum to a successful outcome.

The Australian Government has committed to progress the recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in the Constitution. It is incumbent on the Australian Government to ensure that adequate resources are committed to engage the public in the reform process. It is now time to harness the bipartisan support for change, and truly make this a process of the people.

(i) Expert Panel on Constitutional Recognition of Indigenous Australians

As this Report was being finalised the Australian Government established an Expert Panel on Constitutional Recognition of Indigenous Australians (Expert Panel).

The Expert Panel will report to the Australian Government on potential options for constitutional recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, and will advise on the level of support for these options by December 2011.[121] The Terms of Reference are set out in Text Box 2.8 below.

Text Box 2.8: Expert Panel on Constitutional Recognition of Indigenous Australians: Terms of Reference[122]

In performing [its] role, the Expert Panel will:

- lead a broad national consultation and community engagement program to seek the views of a wide spectrum of the community, including from those who live in rural and regional areas;

- work closely with organisations, such as the Australian Human Rights Commission, the National Congress of Australia's First Peoples and Reconciliation Australia who have existing expertise and engagement in relation to the issue and

- raise awareness about the importance of Indigenous constitutional recognition including by identifying and supporting ambassadors who will generate broad public awareness and discussion.

In performing this role, the Expert Panel will have regard to:

- key issues raised by the community in relation to Indigenous constitutional recognition

- the form of constitutional change and approach to a referendum likely to obtain widespread support

- the implications of any proposed changes to the Constitution and

- advice from constitutional law experts.

The Expert Panel will be central to ensuring that the journey to achieve a successful referendum is community-led – by both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, and non-Indigenous Australians. To better reflect this, I am of the view that the name of the Expert Panel should be changed to the ‘Consultative Committee on Constitutional Recognition of Indigenous Australians’.

The Expert Panel is made up of Indigenous and community leaders, legal experts and parliamentary members, who bring together a wide range of expertise.[123] I have been appointed as an ex offico member of the Expert Panel in my capacity as the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner. The Co-Chairs of the National Congress have also been appointed as ex offico members.

The presence of representatives from the Australian Labor Party, the Australian Greens, the Coalition and an Independent should help ensure that the Expert Panel builds on the early bipartisan support for the reform process. While the Expert Panel contains representatives from across the Parliament, it is heartening to see that it has been structured in a way that minimises perceptions that it is a political body. Only four of the 20 members are parliamentarians.

To strengthen the role of the Expert Panel, I consider that it should be empowered to make recommendations for reform based on the results of the consultation process and its research findings. It should not simply be tasked with suggesting options.

I encourage the Australian Government and the Opposition to make a public commitment to act on the recommendations of the Expert Panel.

I am pleased to have been appointed to the Expert Panel and look forward to being a part of the national conversation with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders and the broader community towards a successful referendum.