7 Preschoolers in detention

- 7.1 Forming relationships

- 7.2 The detention environment

- 7.3 Opportunities for play, learning and development

- 7.4 Impacts on preschoolers

- 7.5 Findings specific to preschoolers

In preschool children we have seen regressed or disturbed behaviour such as needing to cling to parents at night and refusing to sleep in their own bed; separation anxiety; incontinence; uncharacteristic aggression; the development of a stammer; and slowed language development. In nearly all cases the behaviour has emerged during detention, and often after a series of distressing incidents such as family separations and witnessing violence.[279]

Drawing by child, Christmas Island, 2014.

The first five years of a child’s life are the vital building blocks for development. The child’s brain develops more at this time than at any other stage in life.[280] The experiences that the child has during these years will help to form the adult that he or she will become.[281]

The Inquiry has received extensive evidence that the detention centre environment is having a negative impact on the emotional and cognitive development of the 204 pre-schoolers (aged 2 to 4 years) in detention in Australia (at March 2014).[282] The negative impacts of detention on children have been comprehensively documented in Australian and international research.[283]

The Australian Government’s Early Years Learning Framework describes the preconditions for healthy childhood growth and progress. It sets out three foundations for preschooler development: ‘belonging, being and becoming.’[284] Throughout this chapter, the development of preschool children in detention will be framed using the three pillars of this Framework.

7.1 Forming relationships

The first pillar of the Early Years Learning Framework explains that preschoolers need to belong to a family and a community. According to the Framework, a child needs to establish secure relationships with parents, family and community to develop a healthy sense of self. [285]

Belonging is the basis for living a fulfilling life. Children feel they belong because of the relationships they have with their family, community, culture and place.[286]

All evidence to this Inquiry indicates that the institutionalised structure and routine of detention disrupts family functioning and the relationships between parents and children.[287]

... children do not have access to a private family home where it would be expected families would spend time away from other people sharing meals, engaging in shared activities, and having rest-time on their own.[288]

In the normal family environment, parents make most decisions about their child’s development. They determine food choices, play activities and the culture which they want in the family home. Detention limits this autonomy.[289] Along with the children, parents must follow the regime, the rules and the timetable of the detention environment. A child psychiatrist who accompanied the Inquiry team to Christmas Island, Dr Sarah Mares, described the environment in these terms:

Parents are undermined and their powerlessness is reinforced to them and their children in daily humiliations and routines. Families line up in the sun or rain (there is little shelter) and wait, then show ID cards for food (carrying their own issued plastic cup, plate and cutlery), for medicines to be handed out, to see the nurse or doctor. [290]

There are considerable limits to the ways in which parents are able to take on a parental role.

Our son asks us why we need to ask the guards for everything. It is the parent that should provide, but I feel powerless. Our son says that the guards are stronger than we are. Now he is only a child, but I am scared he will be worse when he is a teenager. Already he doesn’t listen to us anymore, I am worried he won’t listen as he gets older and will get into trouble.

(Father of 4 year old child, Melbourne Detention Centre, 7 April 2014)

The authority of parents is subordinate to the rules of the detention environment and children pick up on this power dynamic.

... parents would teach their children to fear and/or respect officers. If they were asking their child to get into a stroller and they weren't listening. They would say to their child, ‘officer is coming’. The child would then look at you and get into the stroller. The child growing up in an environment where the parents can use a higher authority to put fear into their child is foreign to me.[291]

Associate Professor Karen Zwi, a paediatrician who accompanied the Inquiry to Christmas Island described the limits to family life in the following terms:

There’s nowhere where you can feel empowered as a mother, father, to have a family conversation or discipline your children, talk about the future or do things that normal families do.[292]

Children of preschool age are learning socialisation and absorbing society’s values and rules for behaviour. A child of this age does not have the ability to interpret the environment. Rather, he or she will accept the actions and activities of the people around them as normal.[293]

Our son says that he feels that we are robbers, but we are not robbers. He always talks about jail and punishment.

(Mother of 4 year old child, Melbourne Detention Centre, 7 April 2014)

Preschoolers in detention cannot be sheltered from the distress of adults. Children and their parents reported that they heard screaming and crying in the night and witnessed acts of violence, psychosis, self-harm and distress.[294] Children also witness the daily struggles of their parents as they cope with the detention environment. In many cases this leads to a decline in mental health of a mother or father or both.[295]

Over 60 percent of parents in detention reported that they felt depressed ‘most of the time’ or ‘all of the time’ when they were asked to respond to the Inquiry questionnaire.[296] Poor parental mental health impacts directly on preschool aged children. Parents are the primary role models and providers of emotional comfort at this important stage of development.[297]

I’m very concerned about wife’s health... [she’s] very depressed. IHMS gave her medicine, made her sleepy. Children crying a lot, irritable, not obedient, my child said to me ‘go to hell - why did you bring me here?’

(Father of 4 year old child and a baby, Darwin detention centre, 13 April 2014)

According to the Australian Research Alliance for Children and Youth, parents play a critical role in determining the development of the child:

An increasing body of evidence demonstrates how brain development in the early years can set trajectories for learning and development throughout the child’s life. Parents play the most critical role in helping their children’s early development...[298]

Ultimately, children in detention ‘belong’ to a detention community. They learn to relate and form relationships by observing and imitating the adults in the detention environment.

Clinical research into the effects of detention on family relationships shows evidence of attachment disorders in 30 percent of children. After a year of detention, the rates of attachment disorder increase.[299]

7.2 The detention environment

The limitations of the physical environment of detention centres are acute for preschoolers. At a time when children should be exploring their world and testing their abilities, many are confined to living quarters of 3 x 2.5 metres for many hours of the day. These rooms are the only private spaces at Christmas Island detention centres. In Darwin the rooms are slightly bigger. Both places have average daytime temperatures of 30 degrees and these small rooms provide the only respite from the heat:

the housing is dirty, sub-standard, hard to be there. The child keeps hitting his head on items in the room – the bed, the shelf – because of the lack of space.

(Father of 2 year old child, Construction Camp Detention Centre, Christmas Island, 16 July 2014)

He is only four years old and he has as many scars as a Vietnam soldier – he’s had lots of falls, and has scars from mozzie bites.

(Father of 4 year old child, Construction Camp Detention Centre, Christmas Island, 16 July 2014)

A Professor of Paediatrics and Child Health who assisted the Inquiry team on Christmas Island, Elizabeth Elliott, described the health hazards of this detention environment:

A remote, inaccessible island closer to Jakarta than Australia is no place for young children. Cramped living conditions intended for temporary use and overcrowding have dire health consequences, enabling rapid spread of infections. Asthma is common, with episodes of wheeze exacerbated by infection, dust and life lived in air-conditioning in a punishing climate. The long wait for transfer to the mainland for medical or surgical treatment is incomprehensible to families. From a paediatrician’s perspective these delays in treatment - for children with delayed speech, poor hearing, rotten teeth, sleep apnoea and infection – are unacceptable and may have lifelong consequences.[300]

The limitations of the physical environment may have specific impacts on the way in which the child develops a sense of identity. A mother on Christmas Island reported:

I’m worried about my kid. He can’t draw himself because there is no mirror he can reach to see. He has lost the meaning of living in a home. Even at four years he had never seen a mandarin till this week.

(Mother of 4 year old child, Construction Camp Detention Centre, Christmas Island, 16 July 2014)

The Darwin detention centres are surrounded by dense mangroves and at certain times there are sand-flies and mosquitoes. According to a former professional working in Darwin, these environments are dangerous:

[There are] few open spaces for play and the place is elevated and set up on various levels with walkways throughout. The elevation means kids can run under buildings and walkways in an environment where snakes and spiders are prolific.[301]

Christmas Island detention centres are located in carved out sections of the tropical rain forest. The fences of the detention centres do not keep out the crabs, giant centipedes and wild chickens that are prolific on Christmas Island. There are 20 types of crabs on Christmas Island, some of them the size of a football. Children and parents complained of painful stings from the centipedes which find their way into clothing and bedding.

We have found centipedes in our room. They grow to 30 cm and they sting. There are two kinds. The large black one which is not as harmful and the small red one with a painful sting. The authorities spray them then they come into the rooms. Four persons I know have been bitten. There are huge crabs in the camp. The robber crabs live under the huts and come out in cool weather. The red crabs are everywhere.

(Parent of preschool aged children, Construction Camp Detention Centre, Christmas Island, 16 July 2014)

The wildlife on Christmas Island holds a kind of gothic horror for some of the preschool aged children.

Our son is frightened to go outside. He thinks he will be dragged into the forest by an evil spirit and the animals will get him.

(Father of 3 year old child, Construction Camp Detention Centre, Christmas Island, 16 July 2014)

The Melbourne Detention Centre is behind a military complex. It is surrounded by high fences and the families live in converted shipping containers.

My child has increased anxiety; [he is] worried about snakes.

(Mother of 2 year old child, Melbourne Detention Centre, 7 May 2014)

The Sydney and Inverbrackie Detention Centres consist of share houses for families and provide more living space. Nevertheless, the houses are part of a locked environment and parents are not free to take their children to local parks, to the ocean, or to play centres.

In all detention environments, children share living spaces with other adults. Children mix with adults on the walkways between their living quarters, in the dining halls and in all areas outside their family rooms.

Up until July 2014, families living in the (now closed) Aqua and Lilac Detention Centres shared common bathroom facilities. One parent described the impacts of almost 500 people sharing 4 toilets:

The nightmare of Aqua will stay with me the rest of my life.

(Parent of preschool aged children, Construction Camp Detention Centre, Christmas Island, 16 July 2014)

At a time when children are learning toilet training, the shared bathrooms posed many problems. Parents described difficulty in encouraging their children to use the bathrooms because they were dirty.

[The] shared bathroom and toilet is extremely dirty. Children are walking in adult urine, faeces on the floor.

(Parent of 2 year old child and 5 year old child, Aqua Detention Centre, Christmas Island, 3 March 2014)

At Construction Camp Detention Centre where most families on Christmas Island now live, most people said that there were sufficient toilets and showers but several complained that the soap was cheap and hard to lather.

Parents who were not satisfied with the bathroom facilities reported that they were very dirty at 67 percent of responses at Chart 25.

Chart 25: Responses by children and parents to the question: What are the limitations of the toilet and bathroom facilities?

Chart 25 description: Responses by children and parents to the question: What are the limitations of the toilet and bathroom facilities? Very dirty 67%, Not enough toilets and showers 14%, Can't use them 9%, Cleaned once a week 8%, They cleaned them before the Commission came 8%, Too small 3%, Not appropriate for the disabled 2%, Other 6%

Australian Human Rights Commission, Inquiry Questionnaire for Children and Parents in Detention, Australia, 2014, 64 respondents, (Note: respondents can provide multiple responses)

At the Melbourne Detention Centre and at some of the centres on Christmas Island, two families share a 1m x 2.5m bathroom in between their adjoining rooms. In Darwin, each sleeping room has its own bathroom. At the Sydney and Inverbrackie Detention Centres, bathrooms are shared in house accommodation.

Opportunities for physical play are vital to children’s gross motor development. In addition, physical activity contributes to children’s ability to socialise, promotes confidence and independence and supports mental health...[302]

The Australian College of Nursing and Maternal, Child and Family Health Nurses Australia described a number of physical requirements for children to develop during the early years in a submission to this Inquiry.[303] Chart 26 sets out these physical requirements against the availability of resources in each detention centre using the criteria described by the College.

Chart 26: Physical requirements for children in detention

| Physical requirements for children | Christmas Island Construction Camp Detention Centre |

Christmas Island Aqua and Lilac Detention Centres |

Darwin Wickham Point Detention Centre |

Darwin Blaydin Detention Centre |

Darwin Airport Lodge Detention Centre |

Melbourne Detention Centre |

Sydney Detention Centre |

Adelaide Inverbrackie Detention Centre |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adequate protection from the physical environment at all times (including hot and cold weather, excessive sun exposure and insects) | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | YES | YES |

| Appropriate outdoor recreational areas, with adequate shade | NO | NO | NO | YES | NO | NO | YES | YES |

| Access to the natural environment, including grass and trees | NO | NO | YES

Access to grass ovals no trees |

YES Access to grass ovals no trees |

YES Access to grass ovals |

YES | YES | YES |

| An area for indoor exercise and physical games and play | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | YES | YES |

| A dedicated space for educational activities | NO | NO | YES Playgroup room |

YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| A library with reading materials in the languages spoken by the children | NO | NO | YES | YES | NO | NO | NO | NO |

| An accessible meal preparation area for parents to use at any time | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | YES | YES |

| Privacy for individuals and families, including separate areas for attending to children’s needs (such as areas for bathing and quiet areas for daytime naps) | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | YES | YES |

Source: Physical requirement categories from Australian College of Nursing and Maternal, Child and Family Health Nurses Australia[304]

Chart 26 shows that both Sydney and Inverbrackie Detention Centres provide most requirements necessary for the development of preschool children. However, Christmas Island Detention Centres are lacking in every necessary resource for child development. Darwin and Melbourne Detention Centres provide limited resources for children, but lack recreation activities and private places for parents to prepare meals and spend time with their children.

7.3 Opportunities for play, learning and development

States must recognise the right of the child to engage in age appropriate play and recreational activities. (Article 31 Convention on the Rights of the Child)

The Australian Government’s Early Years Learning Framework has a strong emphasis on play-based learning because play provides the most appropriate stimulus for brain development. The Framework describes this as the second pillar in childhood development:

Being is about living here and now. Childhood is a special time in life and children need time to just ‘be’- time to play, try new things and have fun.[305]

At the early stages of childhood development, the child needs to be able to develop fine motor skills and explore his or her independence.[306] Preschool children are likely to be ‘imitating adult actions, speaking and understanding words and ideas’ and developing connections with others.[307] Much of this development occurs through play.

My youngest child has no toys. He only pushes a chair around.

(Parent of preschooler, Aqua Detention Centre, Christmas Island, 6 March 2014)

The availability of toys and play activity for preschool children varies across the detention network. Families with preschool children were asked by the Inquiry team whether there were enough toys and activities for their preschool aged child or children. Chart 27 shows that 33 percent of parents thought that there were not enough resources, while 38 percent were satisfied with the toys and preschool education for their children.

Chart 27: Responses by parents of preschoolers to the question: Are there enough toys, activities and facilities?

Chart 27 description: Responses by parents of preschoolers to the question: Are there enough toys, activities and facilities? Yes 38%, No 33%, Sometimes 26%, Not sure 2%.

Australian Human Rights Commission, Inquiry Questionnaire for Children and Parents in Detention, Australia, 2014, 87 respondents

Most detention centres have a room with some share toys. In most centres there was a timetable for this toy room / playroom and parents needed to pre-book and accompany their child to the session.

The Inquiry team noticed that new toys were bought on the day of the Inquiry visit to the Darwin detention centres. New X-Boxes were also set up in Melbourne Detention Centre for the Inquiry visit. Children and their parents reported that these had never been used.[308]

There were no toys at the Christmas Island detention centres in March when the Inquiry team first visited. At the second visit, toys were seen in the new playroom for children. It is not known whether the children had been able to use them as the playroom was not yet open.[309]

Given that many asylum seeking children have come from places where they have experienced significant trauma, there is arguably a greater need for these children to have access to a stimulating environment with ‘different activities’ and ‘plenty of ways to play and learn.’[310]

Play has been shown to be a vital component in overcoming trauma. Play deprivation has been assessed as a significant contributing factor in a lack of physical brain development, repressed emotions and social skills, depression and withdrawal, as well as behaviour that has been described as bizarre and aggressive, anti-social and violent.[311]

Play is also a human right. Article 31 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child recognises:

... the right of the child to rest and leisure, to engage in play and recreational activities appropriate to the age of the child and to participate freely in cultural life and the arts.

Structured activity is also important for the developing child. Parents living in mainland detention centres reported that preschool activities were available for their children. Parents at Christmas Island detention centres were not satisfied with the offerings for their children as there were no formal or informal preschool activities for the 89 preschoolers there. Chart 28 shows the preschool, crèche or play offerings at the detention centres.

Chart 28: Preschool for children in Australian detention centres

|

Location

|

Number of hours of preschool education, number of places offered[312]

|

Two year olds

|

Three year olds

|

Four year olds

|

Total preschoolers

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Inverbrackie Detention Centre, Adelaide, South Australia

|

4 year old children can attend kindergarten offsite on Tuesday and Wednesday and in the morning on Thursday.

No information about services for children aged 2 and 3. |

18

|

5

|

10

|

33

|

|

Darwin detention centres, Northern Territory

|

4 year old children attend external preschool two days per week from 8:00am to 3:00pm.

The detention service provider delivers playgroup activities for children aged 1-4 years and average attendance is approximately 30 children per day. |

15

|

25

|

17

|

57

|

|

Sydney Detention Centre, New South Wales

|

There were no 4 year old children at the detention centre. Any other activities are not specified. |

0

|

1

|

0

|

1

|

|

Melbourne Detention Centre, Victoria

|

There are two one-hour programs run by the detention services provider each weekday. Approximately 5 children attend in the morning and between 3 and 5 children attend in the afternoon session. |

6

|

5

|

8

|

19

|

| Christmas Island detention centres | There were no scheduled activities for preschool aged children. In July 2014 a playroom was established for children to use on a rotational, rostered basis under parental supervision. | 36 | 31 | 22 | 89 |

Source: Australian Human Rights Commission analysis of data from the Department of Immigration and Border Protection[313]

Some parents reported that their children felt singled out when they attended preschool activity outside the detention environment.

A parent struggles when his child sees other children in the community who are free and can play, eat what they want. Baby cried last time at playgroup wanted to eat what other children are eating, father feels sad he can’t provide for child.

(Parent of 3 year old child, Wickham Point Detention Centre, Darwin, 11 April 2014)

When children leave the detention centre they are required to take the food provided by Serco officers. When children leave the detention centre for activities, they pass through security checks at the gate. This includes bag searches and in some circumstances, body searches.

In addition to preschool, some children have limited opportunities to leave detention centre for excursions under guard by Serco officers. Parents accompany their children on these excursions. Chart 29 sets out the numbers of times that children were able to go on excursions other than preschool.

Chart 29: Responses by parents of preschoolers to the question: How often have your children left the detention centre for an excursion?

Chart 29 description: Responses by parents of preschoolers to the question: How often have your children left the detention centre for an excursion? Never left 7, 1 time 12, 2 times 16, 3 times 9, More than 3 times 16, Other 2

Australian Human Rights Commission, Inquiry Questionnaire for Children and Parents in Detention, Australia, 2014, 62 respondents

Excursions provide some change from the monotony of the detention environment. Of the 62 respondents to the question about excursions, seven reported that their preschooler had never left the detention centre for an excursion, 12 preschoolers had been on one excursion, 16 had been on two excursions and only 3 respondents reported that they had been on an excursion more than once a week.

One time we left the detention centre to go to the park. It was very good. Our son now asks why we don’t go to the park anymore. He asks us to tell him stories of that one day we were allowed to go to the park.

(Mother of 4 year old child, Melbourne Detention Centre, 7 May 2014)

7.4 Impacts on preschoolers

Information provided by the Department of Immigration and Border Protection advised that in March 2014 there were five preschoolers having individualised mental health counselling on Christmas Island. Three of these children were aged 2 years old, one was aged 3 years and one was 4 years old.[314]

The Australian Government Early Years Learning Framework explains that a child forms key aspects of identity during the formative preschool years. The third pillar of the Framework is ‘becoming’:

Becoming is about the learning and development that young children experience.[315]

The most common concern that parents in detention had for their children was the way in which their child was acquiring socialisation skills. Many parents reported that their preschooler was unable to get along with other children. Chart 30 sets out the concerns that parents had about this development.

Chart 30: Responses by parents of preschoolers to the question: What are your concerns about the development of your child?

Chart 30 description: Responses by parents of preschoolers to the question: What are your concerns about the development of your child? Problems socialising with others 30%, Problems talking/speaking 29%, Always upset and distressed 27%, Not able to play 21%, Not able to learn 8%, Problems toileting 3%, Problems walking 3%, Problems crawling 2%, Other 11%

Australian Human Rights Commission, Inquiry Questionnaire for Children and Parents in Detention, Australia, 2014, 63 respondents (Note: respondents can provide multiple responses)

Sixty percent of parents reported concerns about their child’s development at Chart 31.

Chart 31: Responses by parents of preschoolers to the question: Do you have concerns about your child's development including speaking / crawling / walking / running?

Chart 31 description: Responses by parents of preschoolers to the question: Do you have concerns about your child's development including speaking / crawling / walking / running? Yes 60%, No 35%, Sometimes 5%

Australian Human Rights Commission, Inquiry Questionnaire for Children and Parents in Detention, Australia, 2014, 125 respondents

I’ve spoken to IHMS about my children’s symptoms (anxiety, stress, crying) and was told this was normal for detention.

(Parent of children aged 6, 4, and 2 years, Inverbrackie Detention Centre, Adelaide, 12 May 2014)

Concerns about the development of preschool aged children are echoed in a submission to this Inquiry by Occupational Therapy Australia.[316] Occupational Therapy Australia provided weekly support to children in Brisbane Detention Centre during 2013.

Clinical observations by the occupational therapists involved in the program indicate that almost all children in the detention facility experience delays in one or more areas of development (learning, play, social skills, emotional regulation, cognition, physical development)... Engagement in childhood activities decline and social and emotional skills deteriorate the longer children live in a detention environment. [317]

The occupational therapists at Brisbane Detention Centre reported that children are not meeting the same developmental milestones as children in the Australian community:

[There are] notable delays in almost all children in the centre, as compared to children of a relative age in an Australian demographic ...We could say that these children are not meeting developmental milestones according to Australian research ...

Children in detention struggle with awareness of routine, accessing age appropriate spaces and activities, emotional regulation (especially self-calming when upset or over-excited), coping with loss, skills for engaging in groups or with peers, and experiencing success and positive attention.[318]

Parents and visitors to detention centres report that some children lack motivation and show signs of regressing.

Parents explained that their children (some under 5) are unmotivated and ‘sit in the room all day’.’[319]

It was common for parents to tell the Inquiry team that they were concerned about the learning ability of their preschool aged child.

My child has gone backwards with his learning.

(Parent of 4 year old boy, Melbourne Detention Centre, 7 May 2014)

I am concerned my child is not speaking.

(Mother of 2 year old child, Melbourne Detention Centre, 7 May 2014)

Eighty percent of parents reported that the mental health of their preschool aged child had been affected by detention at Chart 32.

Chart 32: Responses by parents of preschoolers to the question: Do you think the emotional and mental health of your child has been affected since being in detention?

Chart 32 description: Responses by parents of preschoolers to the question: Do you think the emotional and mental health of your child has been affected since being in detention? Yes 80%, No 16%, Sometimes 2%, Not sure 2%.

Australian Human Rights Commission, Inquiry Questionnaire for Children and Parents in Detention, Australia, 2014, 96 respondents

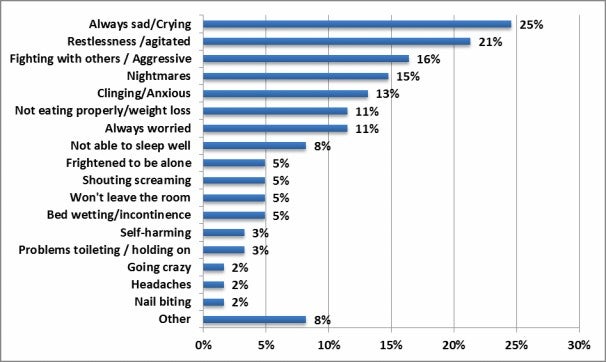

Parents were asked to explain the emotional impacts of detention on their children. The most common response was that their child was always sad and crying at 25 percent of responses. Parents also expressed concern that their children showed worrying levels of restlessness and agitation at 21 percent; while 16 percent of respondents said that their child was aggressive and fighting with others. Parental responses to questions regarding the emotional impacts of detention are at Chart 33.

Chart 33: Responses by parents of preschoolers to the question: What are the emotional and mental health impacts on your child?

Chart 33 description: Responses by parents of preschoolers to the question: What are the emotional and mental health impacts on your child? Always sad/crying 25%, Restlessness/agitated 21%, Fighting with others/aggressive 16%, Nightmares 15%, Clinging/anxious 13%, Not eating properly/weight loss 11%, Always worried 11%, Not able to sleep well 8%, Frightened to be alone 5%, Shouting/screaming 5%, Won't leave the room 5%, Bed wetting/incontinence 5%, Self-harming 3%, Problems toileting/holding on 3%, Going crazy 2%, Headaches 2%, Nail biting 2%, Other 8%

Australian Human Rights Commission, Inquiry Questionnaire for Children and Parents in Detention, Australia, 2014, 61 respondents (Note: respondents can provide multiple responses)

Child and Family Psychiatrist Dr Sarah Mares who visited Christmas Island with the Inquiry team noted a combination of developmental and emotional impacts on children in detention there:

The distress of even very young children was evident in many of those we met, with tearfulness or anxiety, delayed or absent speech and parental reports of children crying themselves to sleep at night, nightmares and regression such as bedwetting.[320]

At Christmas Island there were almost no opportunities for structured learning, no toys and very limited activity. Dr Mares noted the following:

Children who are prevented from playing and learning, are frightened or frustrated can develop difficult behaviours such as emotional outbursts/tantrums, sleep disturbance, nightmares, nail biting, head banging, poor concentration, walking around in an agitated state, failure to listen to parents’ requests and playing out their distress in their games...This was evident in many of the children we saw.[321]

Parents provided examples of these behaviours to the Inquiry.

My daughter is 2 years old. Five months ago she started behaving abnormally. She wakes up screaming and crying in the middle of the night. She always hits us; she pulls my hair and scratches our faces. She has tantrums every day. She broke my glasses. She gets upset without any reason. We sent a request to mental health and we are still waiting our turn.

(Parent of 2 year old girl, Wickham Point Detention Centre, Darwin, 11 April 2014)

He’s different from other lads. He is scared. The first time he went outside [the detention centre] he cried.

(Parent of preschool aged child, Wickham Point Detention Centre, Darwin, 11 April 2014)

[My] son is very scared of the officers, says we should get out of here.

(Father of 2 year old, Inverbrackie Detention Centre, Adelaide, 12 May 2014)

7.5 Findings specific to preschoolers

Detention is impeding the development of preschool aged children and has the potential to have lifelong negative impacts on their learning, emotional development, socialisation and attachment to family members and others.

Preschoolers are exposed to unacceptable risks of harm in the detention environment.

Lack of access to preschool activity for children who arrived on or after 19 July 2013 has learning and developmental consequences for children at this critical stage of brain development.

Detention impacts on the health, development and safety of preschoolers. At various times preschoolers in detention were not in a position to fully enjoy the following rights under the Convention on the Rights of the Child:

- the right to the highest attainable standard of health (article 24(1)); and

- the right to enjoy ‘to the maximum extent possible’ the right to development (article 6(2)) and the associated right to a standard of living adequate for the child’s physical, mental, spiritual, moral and social development (article 27(1)).

The Committee on the Rights of the Child recognises that:

Under normal circumstances, young children form strong mutual attachments with their parents or primary caregivers. These relationships offer children physical and emotional security, as well as consistent care and attention. Through these relationships children construct a personal identity and acquire culturally valued skills, knowledge and behaviours. (General Comment No 7, paragraph 16).

The Committee has accordingly urged States parties:

to take all necessary steps to ensure that parents are able to take primary responsibility for their children; to support parents in fulfilling their responsibilities, including by reducing harmful deprivations, disruptions and distortions in children’s care (See General Comment No 7, paragraph 18).

The institutionalised structure and routine of detention distorts the relationships between parents and children and the care which parents can provide for their children.

The detention environments in all centres in which children are held also limit children’s development by restricting their opportunities for physical play and learning, both alone and with other children. Children in detention have very few opportunities to explore new environments outside of the centres. The Committee on the Rights of the Child has emphasised that:

Play is one of the most distinctive features of early childhood. Through play, children both enjoy and challenge their current capacities, whether they are playing alone or with others. The value of creative play and exploratory learning is widely recognized in early childhood education. Yet realizing the right to rest, leisure and play is...hindered by a shortage of opportunities for young children to meet, play and interact in childcentred, secure, supportive, stimulating and stressfree environments. (General Comment No 7, paragraph 34)

- the right to be protected from all forms of physical or mental violence (article 19(1))

Preschoolers in detention cannot be sheltered from the distress of adults who engage in acts of violence and self-harm. The Committee on the Rights of the Child highlights in General Comment 7 at paragraph 36(a) that ‘[y]oung children are least able to avoid or resist, least able to comprehend what is happening and least able to seek the protection of others.’

[279]G Coffey, Submission No 213 to National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014, p 7. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014-0 (viewed 21 August 2014).

[280]Australian Research Alliance for Children and Youth, Engaging families in the early childhood development story. At https://www.aracy.org.au/projects/engaging-families-in-the-early-childhood-development-story (viewed 2 September 2014).

[281]Raising Children Network, the Australian Parenting Website, Preschooler Development, 2006 - 2014. At http://raisingchildren.net.au/development/preschoolers_development.html (viewed 9 September 2014).

[282]Australian Human Rights Commission, Inquiry Questionnaire for Parents and Children in Detention, Australia 2014, Response to question: What have been the emotional and mental health impacts of detention on your preschool-aged child? 64 respondents.

[283]S Mares and J Jureidini, ‘Psychiatric Assessment of Children and Families in Immigration Detention: Clinical, Administrative and Ethical Issues’. (2004) 28 Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health pp 520-526; Royal Australasian College of Physicians, Submission No 103 to the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014, p 1. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014-0 (viewed 2 September 2014); A Lorek, K Ehntholt, A Nesbitt, E Wey, C Githinji, E Rossor, R Wickramasinghe

‘The mental and physical health difficulties of children held within a British immigration detention centre: A pilot study’ (2009) 33 Child Abuse and Neglect pp 573–585. At http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0145213409001689 (viewed 16 September 2014).

[284]Australian Government Department of Education, National Quality Framework for Early Childhood Education and Care, Early Years Learning Framework November 2013. At http://education.gov.au/early-years-learning-framework (viewed 14 August 2014).

[285]Australian Government Department of Education, National Quality Framework for Early Childhood Education and Care, Early Years Learning Framework November 2013. At http://education.gov.au/early-years-learning-framework (viewed 14 August 2014).

[286]Australian Government Department of Education, National Quality Framework for Early Childhood Education and Care, Early Years Learning Framework November 2013. At http://education.gov.au/early-years-learning-framework (viewed 14 August 2014).

[287]Dr S Mares, Child Psychiatrist; Expert report to the Australian Human Rights Commission after the visit to the Christmas Island Immigration Detention Centres, March 2014. At https://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014/expert (viewed 10 September 2014).

[288]Occupational Therapy Australia, Submission No 74 to the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014, p 7. At https://www.humanrights.gov.au/sites/default/files/Submission%20No%2074%20-%20Occupational%20Justice%20Special%20Interest%20Group.pdf (viewed 11 August 2014).

[289]Associate Professor K Zwi, First Public Hearing of the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014, Sydney, 4 April 2014. At https://www.humanrights.gov.au/sites/default/files/Professor%20Zwi.pdf (viewed 28 August 2014).

[290]Dr S Mares, Child Psychiatrist; Expert report to the Australian Human Rights Commission after the visit to the Christmas Island Immigration Detention Centres, March 2014. At https://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014/expert (viewed 10 September 2014).

[291]Name withheld, Christmas Island and Darwin volunteer, Submission No 114 to the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014. At https://www.humanrights.gov.au/sites/default/files/Submission%20No%20114%20-%20Name%20withheld%20-%20Christmas%20Island%20and%20Darwin%20Volunteer%20in%202010_0.doc (viewed 28 August 2014).

[292]Associate Professor K Zwi, First Public Hearing of the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014, Sydney, 4 April 2014. At https://www.humanrights.gov.au/sites/default/files/Professor%20Zwi.pdf (viewed 28 August 2014).

[293]Encompass, How Children Develop and Learn. At http://encompassnw.org/DownFiles/DL34/CC4_Ch1_exrpt.pdf (viewed 9 September 2014).

[294]Australian Human Rights Commission, Inquiry Questionnaire for Parents and Children in Detention, Australia 2014, Responses to question: What are your safety concerns in detention? Pre-school children, 46 respondents.

[295]Australian Human Rights Commission, Inquiry Questionnaire for Parents and Children in Detention, Australia 2014, Responses to question: How often do you feel depressed? Parents of children in detention, 253 respondents.

[296]Australian Human Rights Commission, Inquiry Questionnaire for Parents and Children in Detention, Australia 2014, Responses to question: How often do you feel depressed? Parents of children in detention, 253 respondents.

[297]Raising Children Network, the Australian Parenting Website, Preschooler Development, 2006 - 2014. At http://raisingchildren.net.au/development/preschoolers_development.html (viewed 9 September 2014).

[298]Australian Research Alliance for Children and Youth, Engaging families in the early childhood development story. At https://www.aracy.org.au/projects/engaging-families-in-the-early-childhood-development-story (viewed 2 September 2014)

[299]S Mares, J Jureidini, ‘Child and adolescent refugees and asylum seekers in Australia: the ethics of exposing children to suffering to achieve social outcomes’ (2012) in M Dudley, D Silove, F Gale (eds) Mental health in human Rights: Vision, Praxis and Courage (2012) OUP; S Mares and J Jureidini ‘Psychiatric Assessment of Children and Families in Immigration Detention: Clinical, Administrative and Ethical Issues’. (2004) 28 Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health pp 520-526.

[300]Professor E Elliott, Paediatrics and Child Health, Children's Hospital, Westmead, Email Correspondence to the Commission, National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention, 26 September 2014; M Dudley, D Silove, F Gale (eds) Mental health and Human Rights: vision, praxis and courage (2012)

[301]Name withheld, Submission No 28 to the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014, pp 1-2. At https://www.humanrights.gov.au/sites/default/files/Submission%20No%2028%20-%20Name%20withheld%20-%20Former%20professional%20working%20in%20immigration%20detention_0.pdf (viewed 20 August 2014).

[302]Australian College of Nursing and Maternal, Child and Family Health Nurses Australia, Submission 136 to the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014 pp 3-4. At https://www.humanrights.gov.au/sites/default/files/Submission%20No%20136%20-%20Australian%20College%20of%20Nursing%20and%20Maternal%2C%20Child%20and%20Family%20Health%20Nurses%20Australia.pdf (viewed 14 August 2014).

[303]Australian College of Nursing and Maternal, Child and Family Health Nurses Australia, Submission 136 to the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014 pp 3-4. At https://www.humanrights.gov.au/sites/default/files/Submission%20No%20136%20-%20Australian%20College%20of%20Nursing%20and%20Maternal%2C%20Child%20and%20Family%20Health%20Nurses%20Australia.pdf (viewed 14 August 2014).

[304]Australian College of Nursing and Maternal, Child and Family Health Nurses Australia, Submission 136 to the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014 pp 3-4. At https://www.humanrights.gov.au/sites/default/files/Submission%20No%20136%20-%20Australian%20College%20of%20Nursing%20and%20Maternal%2C%20Child%20and%20Family%20Health%20Nurses%20Australia.pdf (viewed 14 August 2014).

[305]Australian Government Department of Education, National Quality Framework for Early Childhood Education and Care, Early Years Learning Framework November 2013. At http://education.gov.au/early-years-learning-framework (viewed 14 August 2014).

[306]The World Bank, Early Childhood Development, What is Early Childhood Development? Development Stages. At http://go.worldbank.org/BJA2BPVW91, (viewed 11 August 2014).

[307]The World Bank, Early Childhood Development, What is Early Childhood Development? Development Stages. At http://go.worldbank.org/BJA2BPVW91, (viewed 11 August 2014).

[308]Australian Human Rights Commission visit to Melbourne Detention Centre, File note, 7 May 2014.

[309]Australian Human Rights Commission visit to Christmas Island Detention Centres, File note, 5 March 2014 and 15 July 2014.

[310]Raising Children Network, the Australian Parenting Website, Preschooler Development, 2006 - 2014. At http://raisingchildren.net.au/development/preschoolers_development.html (viewed 9 September 2014).

[311]M Fourer and R McConaghy, Submission No 163 to the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014, pp 6-7. At https://www.humanrights.gov.au/sites/default/files/Submission%20No%20163%20-%20Margarita%20Fourer%20%26%20Ric%20McConaghy.pdf (viewed 15 August 2014).

[312]Department of Immigration and Border Protection, Revised – Nature of education services available, Item 10, Document 10.1R, Schedule 2, First Notice to Produce 31 March 2014

[313] Department of Immigration and Border Protection, Revised – Nature of Education Services Available, Item 10, Document 10.1R, Schedule 2, First Notice to Produce, 31 March 2014.

[314]K Constantinou, Assistant Secretary AHRC Inquiry Taskforce, Department of Immigration and Border Protection, Correspondence to the Commission, AHRC request for information from CI visit – DIBP response 12 05 2014, 12 May 2014, p 10.

[315]Australian Government Department of Education, National Quality Framework for Early Childhood Education and Care, Early Years Learning Framework November 2013. At http://education.gov.au/early-years-learning-framework (viewed 14 August 2014).

[316]Occupational Therapy Australia, Submission No 74 to the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014. At https://www.humanrights.gov.au/sites/default/files/Submission%20No%2074%20-%20Occupational%20Justice%20Special%20Interest%20Group.pdf (viewed 11 August 2014).

[317]Occupational Therapy Australia, Submission 74 to the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014, p 6. At https://www.humanrights.gov.au/sites/default/files/Submission%20No%2074%20-%20Occupational%20Justice%20Special%20Interest%20Group.pdf (viewed 11 August 2014).

[318]Occupational Therapy Australia, Submission No 74 to the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014, p 6, p.14. At https://www.humanrights.gov.au/sites/default/files/Submission%20No%2074%20-%20Occupational%20Justice%20Special%20Interest%20Group.pdf (viewed 11 August 2014).

[319]Darwin Asylum Seeker Support and Advocacy Network, Submission 222 to the Australian Human Rights National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014, p 5. June 2014. At https://www.humanrights.gov.au/sites/default/files/Submission%20No%2022…

(viewed 21 August 2014).

[320]Dr S Mares, Child Psychiatrist; Expert report to the Australian Human Rights Commission after the visit to the Christmas Island Immigration Detention Centres, March 2014. At https://www.humanrights.gov.au/sites/default/files/Expert%20Report%20-%20Dr%20Mares%20-%20Christmas%20Island%20March%202014_0.doc (viewed 30 October 2014).

[321]Dr S Mares, Child Psychiatrist; Expert report to the Australian Human Rights Commission after the visit to the Christmas Island Immigration Detention Centres, March 2014. At https://www.humanrights.gov.au/sites/default/files/Expert%20Report%20-%20Dr%20Mares%20-%20Christmas%20Island%20March%202014_0.doc (viewed 30 October 2014).