8. Safety of Children in Immigration Detention

A last resort?

National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention

8. Safety of Children in Immigration Detention

Recognizing that the child, for the full and harmonious development of his or her personality, should grow up in a family environment, in an atmosphere of happiness, love and understanding ...

Convention on the Rights of the Child, Preamble

The Commonwealth, through the Department of Immigration and Multicultural and Indigenous Affairs (the Department or DIMIA), has a responsibility to ensure the safety and security of all people in immigration detention, with a special responsibility for children due to their vulnerability.

The Inquiry received evidence that the safety of children in detention was threatened by exposure to riots, demonstrations, acts of self-harm and assaults that occurred within detention centres. Furthermore, sometimes the measures designed to address these security concerns compromised the physical and psychological well-being of children. The use of tear gas and water cannons were obvious examples of measures taken in the name of safety and security but which had the effect of making children feel unsafe and frightened. These are not threats to which children in the community are likely to be exposed.

This chapter focuses on the heightened risk of physical and mental harm to children when they are held in immigration detention centres and evaluates the effectiveness of the measures taken to protect children within that context. It also considers whether the safety of children can ever be fully protected within the constraints of the detention centre environment.

The psychological impact of detention is developed further in Chapter 9 on Mental Health. The following questions are addressed in this chapter:

8.1 What are children's rights regarding safety in immigration detention?

8.2 What policies were in place to ensure the safety of children in detention?

8.3 What exposure have children had to riots, violence and self-harm in detention centres?

8.4 What exposure have children had to 'security' measures used in detention centres?

8.5 What exposure have children had to direct physical assault in detention centres?

At the end of the chapter there is a summary of the Inquiry's findings and a case study which describes a six-year-old Iraqi boy's exposure to violence at Woomera and Villawood.

8.1 What are children's rights regarding safety in immigration detention?

- States Parties shall take all appropriate legislative, administrative, social and educational measures to protect the child from all forms of physical or mental violence, injury or abuse, neglect or negligent treatment, maltreatment or exploitation, including sexual abuse, while in the care of parent(s), legal guardian(s) or any other person who has the care of the child.

- Such protective measures should, as appropriate, include effectiveprocedures for the establishment of social programmes to provide necessary support for the child and for those who have the care of the child, as well as for other forms of prevention and for identification, reporting, referral, investigation, treatment and follow-up of instances of child maltreatment described heretofore, and, as appropriate, for judicial involvement.

Convention on the Rights of the Child, article 19

The Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) takes the obligation to protect children from all forms of mental and physical violence extremely seriously. It sets a high threshold for compliance by requiring Australia to take 'all appropriate legislative, administrative, social and educational measures' to ensure that children are protected from all types of violence, abuse or neglect caused by a child's parent or any other person who is caring for the child. In the detention environment this means that the Department and Australasian Correctional Management Pty Limited (ACM) must take positive steps to ensure that children are protected from physical or mental violence, abuse or neglect in detention, irrespective of its source.

Article 3(2) requires Australia to ensure that all children who are in detention centres receive 'such protection and care as is necessary for his or her well-being, taking into account the rights and duties of his or her parents'. Furthermore, article 3(3) provides that:

States Parties shall ensure that the institutions, services and facilities responsible for the care or protection of children shall conform with the standards established by competent authorities, particularly in the areas of safety, health, in the number and suitability of their staff, as well as competent supervision.

This means that the Department has the obligation to ensure that there are standards in place so as to provide, to the maximum extent possible, an environment where children can feel safe and are protected from exposure to any violence.

Since asylum seekers and refugees are often fleeing situations of violence, they may be especially vulnerable, particularly in a psychological sense, to the impact of violence in detention. Article 19 must therefore be read with articles 6(2), 22(1) and 39 of the CRC which together require that appropriate measures be taken to ensure that refugee and asylum-seeking children grow up in an environment which fosters, to the maximum extent possible, development and rehabilitation from past trauma. Thus the requirement to protect children from violence extends beyond preventing direct abuse.

Further, in recognition of the special vulnerabilities of women and girls to violence, the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) obliges Australia to pursue positive measures to eliminate all forms of violence against women and girls, including physical, mental or sexual harm and suffering, threats of such acts, coercion and other deprivations of liberty.(1)

The CRC also requires that detainee children are treated with humanity and respect for the inherent dignity of the child:

Every child deprived of liberty shall be treated with humanity and respect for the inherent dignity of the human person, and in a manner which takes into account the needs of persons of his or her age. In particular, every child deprived of liberty shall be separated from adults unless it is considered in the child's best interest not to do so.

Convention on the Rights of the Child, article 37(c)

Although Australia has made a reservation to the requirement that children in any detention facility (including prisons) must be separated from adults, the Minister for Immigration and Multicultural and Indigenous Affairs (the Minister) has recognised the importance of separating families in immigration detention from other adults (see section 8.5.1 below).(2) Separation of women and child detainees from men is also a practice recommended by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees Guidelines on Detention which provide that 'where women asylum seekers are detained they should be accommodated separately from male asylum seekers, unless these are close family relatives,'(3) and where children are detained they should be separate from adults except where they are in a family group.(4)

The United Nations Rules for the Protection of Juveniles Deprived of their Liberty (the JDL Rules) provide some guidance as to how children might be protected from violence within a detention environment. The JDL Rules acknowledge an inherent conflict between maintaining a secure detention facility while also creating an environment within which children feel safe and can develop and grow. For example, the JDL Rules recommend that any surveillance during sleeping hours should be aimed at protecting children and should be 'unobtrusive'.(5) The use of force and other 'control methods' regarding children should only be used in exceptional circumstances, under the order of the director of the facility and subject to higher review.(6)

The JDL Rules also provide that the conditions of detention should 'ensure their protection from harmful influences and risk situations'.(7) All staff in the detention facility 'should respect and protect the human dignity and fundamental human rights of all juveniles'. In particular:

All personnel should ensure the full protection of the physical and mental health of juveniles, including protection from physical, sexual and emotional abuse and exploitation, and should take immediate action to secure medical attention whenever required.(8)

Article 3(1) of the CRC requires Australia to ensure that the best interests of the child are a primary consideration in all actions concerning children, including those that might impact on a child's physical or psychological safety. When article 19(1) is read with article 3(1) it is clear that it is inadequate to simply consider how children can best be protected within a detention centre (although such consideration is clearly vital). A consideration of the best interests of the child necessarily includes an assessment of whether a child's safety can ever be properly protected within a detention environment. If not, appropriate legislative or administrative measures should be taken.

8.2 What policies were in place to ensure the safety of children in detention?

8.2.1 Department policy regarding safety and security

The Department acknowledges the obligation to protect children from harm while they are in immigration detention:

The Department and Services Provider make every effort to prevent undesirable or harmful actions occurring in immigration detention facilities, and to ensure that children are not exposed to them.(9)

Throughout the period of the Inquiry, the primary mechanism through which the Department established standards governing safety and security in detention, was the Immigration Detention Standards (IDS). The IDS imposed contractual obligations on ACM.

(a) Immigration Detention Standards on security

The IDS require that '[d]etainees, staff and visitors are safe and feel secure in the facility',(10)and that '[t]he security of buildings, contents and people within the facility is safeguarded'.(11)

The IDS also require that detainees be prevented from accessing any implement that could be used as a weapon.(12) These standards apply equally to children and adults. Staff are required to:

monitor tensions within detention facilities and take action to manage behaviour to forestall the development of disturbances or personal disputes between detainees. If these occur, they are dealt with swiftly and fairly to restore security to all in the facility.(13)

The standards also set out the means of discipline which are permissible within the facilities. They state that:

Prolonged solitary confinement for security reasons, punishment by placement in a dark cell, reduction of diet, sensory deprivation and all cruel, inhumane or degrading punishments are not used.(14)

While prolonged solitary confinement is not allowed, short term isolation appears to be contemplated as the standards state that if a detainee is placed in 'solitary confinement for security reasons, a qualified medical officer visits daily and ensures that the continued separation is not having a deleterious effect on physical or mental health'.(15) While there is no specific prohibition on solitary confinement of children, both the Department and ACM deny that children were confined for punishment reasons (see below section 8.4.6).

The IDS contain requirements governing the use of force, which may only be used as 'a last resort', and instruments of restraint (like handcuffs), the use of which is limited.(16)

All of these standards apply equally to adults and children; however, the IDS also state that 'detainees are responsible for the safety and care of their child/children living in detention'.(17)

Neither the IDS (nor the Handbook - see below) contain specific statements regarding special measures to ensure the safety and security of children, nor do they specify whether or not solitary confinement and other behaviour management strategies can be employed with children. The Department states that the broad application of the IDS and State child protection laws, taken in the context of the primary responsibility of parents to protect their children, adequately safeguards the interests of children.(18) This chapter explores whether or not that is the case in practice.

(b) Department Managers' Handbook

The Department has also created a handbook to guide Departmental Managers of detention facilities (the Handbook). The Handbook elaborates on the IDS and reflects corresponding provisions of the Migration Act 1958 (Cth) (Migration Act). The Handbook states that:

As officers under the Migration Act, DIMIA staff are also empowered to use reasonable force in certain circumstances but it is expected that the need for this in [detention centres] would be rare given the Services Provider's role and responsibilities.

In the immigration detention context, the Migration Act and Regulations provide the power to use reasonable force to:

- take a person into immigration detention;

- keep a person in immigration detention;

- cause a person to be kept in immigration detention. This includes preventing a detainee from escaping from detention;

- conduct a search of a detainee;

- identify a detainee; and

- provide non-consensual medical treatment to a detainee in a detention centre in specific circumstances.(19)

Department Managers have the final say on the use of force:

It is the DIMIA Manager's responsibility to monitor any use of force undertaken by the Services Provider to ensure consistency with the Migration Act and the IDS.(20)

The Handbook also states that:

Instruments of restraint and chemical agents, including flexi-cuffs and tear gas, are forms of force and must be used only in accordance with the principles relating to the use of reasonable force. They must never be applied as a punishment.(21)

The Handbook also outlines the search powers within immigration detention facilities.

(c) Monitoring of security practices

As discussed in Chapter 5 on Mechanisms to Protect Human Rights, one of the primary mechanisms by which the Department monitors safety and security of detainees is through the provision of incident reports, which are required by the IDS. Briefly, the IDS require that:

Any incident or occurrence which threatens or disrupts security and good order, or the health, safety or welfare of detainees is reported fully, in writing, to the DIMIA Facility Manager immediately and in writing within 24 hours.(22)

Chapter 5 describes the incident reporting system and discusses some of its weaknesses, including problems with the quality and timeliness of reporting by ACM.

8.2.2 ACM policy regarding safety and security

ACM has developed a range of policies to implement the security and safety requirements of the IDS, one of which is specific to the protection of children. The Child Protection Policy, first introduced at Woomera in February 2001, sets out the procedures to be followed when it is believed that:

- the child has or is likely to suffer physical or psychological injury; or

- the child's physical or psychological development is in jeopardy.(23)

The general child protection policy for all centres, introduced in August 2001, states that:

All ACM staff will comply with the Children's Protection Act of the State or Territory in which the Centre is located. Children and young people have the right to be emotionally and physically safe at all times.

The policy specifies that ACM staff must notify the relevant State child protection agency of any suspected child abuse(24) and that assaults involving children must be reported to both police and the relevant State children protection agency.(25) ACM policies also require that State agencies be notified in the event that a child goes on hunger strike.(26)

While the Child Protection Policy is the only security policy that focuses on children, there are some others that incorporate special measures for child detainees. For example:

- 'Pat searching' of children is restricted to 'the most exceptional circumstances, and based on sound reasoning'.(27) If a child is searched in this way, another person must be present at all times.

- Detainees under the age of 10 must not be strip searched, and a Magistrate's order is required before a strip search is conducted of a 'minor who is at least 10 but under 18 years of age'.(28)

-

ACM must 'not use handcuffs to restrain females, children or intellectually disabled unless special circumstances exist' when escorting a detainee to a place outside the detention centre (such as to the Refugee Review Tribunal, court, hospital, airport, prison or police cells).(29)

However, the majority of ACM's security policies do not specifically differentiate between the treatment of adults and children. Some of the areas covered by those policies include:

- Use of tear gas which 'should only be used as a last resort in circumstances where there is a real threat to life and limb'.(30) Clear warnings must be given to detainees prior to the use of tear gas, and clear instructions to those not wanting to participate any further in 'unlawful behaviour'.

- Emergency management.(31)

- Searches of detainees' rooms.(32)

- Detainee head counts, which require staff to 'physically sight the detainee. If the detainee is covered with bedding staff must pull back the sheet/blanket so the detainee can be identified'.(33)

- Behaviour management through isolation or transfer of a detainee who breaches the detainee code of conduct.(34)

- 'Management separation' which allows for the separation of detainees.(35)

- The use of force and restraints (other than for external escorts).(36)

- Management of detainees who are at risk of self-harm or abuse. This policy sets out the operation of the High Risk Assessment Team (HRAT) - an observation system.(37) The policy contains a list of risk indicators, and signs to observe in determining whether a detainee is at risk of self-harm.(38) The HRAT process is also used to keep a watch on detainees who are vulnerable to abuse.

There is no policy on the use of water cannons.

ACM states that these policies represent best practice and 'transcend the differentiation between adult and child':

ACM policies on riots and security do not make special provision for children because they do not need to. These policies aim to protect all detainees regardless of age or sex, from acts of violence from other detainees and address any measures that may be necessary to prevent the escalation of incidents.(39)

ACM also stated that while its policies regarding riots and security do not make special provision for children, they do incorporate 'fundamental principles of (a) preservation of life and property ... and (b) proportionality'.(40)

While the Inquiry acknowledges that the security policies covered children in principle, in the Inquiry's view, there should have been specific instructions to take special measures to protect children during violent disturbances. This is discussed further in sections 8.3 and 8.4.

8.2.3 State child protection agencies

All Australian States and Territories have child protection legislation and authorities charged with implementing that legislation.(41) Broadly speaking, child protection authorities deal with the protection of children from abuse and neglect. For example, in the community, a child protection authority may be called in to remove a child from a dangerous situation at home in the event of suspected assault or neglectful treatment at the hand of a child's carer.

The Department recognises that State child protection authorities have special expertise in child welfare and relies on them for advice on how to manage and protect children in detention.(42) In the detention context, conditions of neglect which may require the intervention of a child welfare agency can include the conditions in the detention centre itself. Chapter 9 on Mental Health addresses the role of State authorities in responding to the impact of that environment generally.

The detention environment also places children at heightened risk of becoming the victims of, or exposed to, specific acts of violence. The following sections focus on the role of child protection authorities in protecting children from specific instances of abuse or neglect.

Whether or not the State authority can properly fulfil their protection role depends on three factors:

- appropriate reporting procedures

- access to detention facilities to investigate any notifications

- the power to implement its recommendations.

This chapter primarily discusses the South Australian child protection authority. In South Australia, the Department of Human Services (DHS) is responsible for child protection and child welfare. Family and Youth Services (FAYS) is the section of DHS that manages these responsibilities.

In Western Australia the Department for Community Development (DCD) is responsible for child protection.

(a) Reporting of child abuse to child protection agencies

Effective interaction between the Department, ACM and State child protection agencies starts with appropriate reporting procedures. In NSW, SA and Victoria, State parliaments have enacted mandatory reporting obligations for incidents of suspected child abuse or mistreatment for various classes of professionals.(43) In Western Australia, there are no such mandatory reporting provisions, but any person may report their concerns to the Department of Community Development.(44)

The February 2001 Flood Report investigated the incidence of and procedures for dealing with child abuse in immigration detention between 1 December 1999 and 30 November 2000. The Flood Report expressed concern about ACM's delay in developing a policy that clearly set out the reporting responsibilities of staff under State child protection laws:

The new Child Protection Policy [for Woomera] is a thorough yet very overdue document which clearly outlines the responsibilities of staff under the Child Protection Act (SA). I remain unsatisfied that this policy has still not been implemented and that similar documents have not been developed for the other centres and I recommend that ACM address this issue immediately. The sexual assault policy also does not adequately address issues such as the needs of victims of sexual assault after they have been examined and returned to the centre.(45)

The Woomera Department Manager's report for the January 2001 quarter also indicated a lack of clarity in reporting procedures:

I was amazed by an allegation of child abuse, which was supposedly advised to me on a day I was testifying in Court in Adelaide. It was not notified to [the State child protection authority] in a timely manner ....A strong message is needed that this issue is a legal requirement and [DIMIA] nationally views it in the strongest possible terms.(46)

Furthermore, DHS expressed concern that, prior to early 2001 when negotiations began regarding a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with the Department on the issue of reporting, ACM staff believed that they were restricted from reporting child abuse and neglect because of confidentiality clauses in their employment contracts:

Staff employed at detention centres are required to sign a contract of employment that includes a confidentiality clause. Prior to the drafting of the South Australian MOU with DIMIA there was some tension in determining whether staff employed understood their obligations to make notifications under State law. Mandated notifier training is now [as at May 2002] provided to all staff at the detention centre and this has provided greater clarity about roles and responsibilities in relation to child protection notification.(47)

Submissions from the Alliance of Professionals Concerned about the Health of Asylum Seekers and their Children, and Australian Lawyers for Human Rights, also raised this conflict.(48) However, two doctors on short term contracts at Woomera gave evidence that they had not been asked to sign any confidentiality agreement and that it would not have changed the way they administered health care in any (49) case.

Another source of confusion may have been that, prior to the introduction of the Woomera Child Protection Policy in February 2001, staff were under the impression that they had to report their concerns to ACM management rather than to the child protection authorities directly.(50) For example, a former ACM nurse who worked on three six week contracts between August 2000 and February 2001 at Woomera testified that:

During my first two contracts with ACM, medical staff were instructed that they were not allowed to report child protection concerns directly to FAYS, but that we should report to management who would then notify FAYS. This requirement was detailed in the ACM policy manual. This policy was changed in early 2001 following the expression of concern from medical staff. Medical staff were then allowed to notify FAYS, and subsequently notify the ACM centre manager that they had done so.

In January 2001 I notified ACM management of an alleged instance of sexual assault of an unaccompanied minor. This incident was investigated by the South Australian police and FAYS were notified by ACM staff.(51)

The introduction of the Child Protection Policy for Woomera in February 2001, and the general protection policy in August 2001, appear to have gone a long way toward clarifying the reporting procedures.(52) While the Flood Report expressed concern about the level of training accompanying these policies it appears that there were substantial improvements in the level of reporting over 2001.(53) For example, the South Australian child protection authority stated that as at May 2002:

[T]he mandate of notification responsibilities of staff at Woomera has become commonplace. All the arguments that we came across in 2000 are now null and void and it is now part of ACM policy and they have altered their contracts [and had] stuff around the confidentiality clause changed to make it very clear and as I understand there's actually repercussions for ACM staff for not notifying.(54)

A former ACM Activities Officer who worked at Woomera from May 2000 to January 2002 also stated that:

Staff were made aware of the mandatory reporting requirement in relation to suspicion of child abuse or neglect. I was not aware of any matters that should have been reported to FAYS that were not reported.(55)

The Inquiry welcomes the improvements in the reporting procedures and practice regarding child abuse notification. However, given the presence of children in immigration detention since at least 1992, the Inquiry is concerned that a matter of such obvious importance was not specifically anticipated by the Department at a much earlier stage.

(b) Access to detention centres to investigate notifications

State child protection staff do not appear to have encountered problems in accessing detention centres to investigate child protection notifications. The Department explains that the Commonwealth Places (Application of Laws) Act 1970 empowers State authorities to enter immigration detention facilities to investigate specific allegations of child abuse. Therefore the only discussion between the State authorities and the Department would have related to arrangements as to a suitable time.(56)

DHS and DCD confirm that they have been granted access to detention facilities to conduct child abuse investigations and any necessary follow-up visits.(57) However, DCD also stated that it was made clear to them that access is in the control of the Department:

We have not had an instance in relation to child maltreatment where we have had any problems with access into the detention centre at this point. But we are always very clear, and it is always made very clear and we are very aware as well, that it is not something that we have a right of open access to. It has to be on the basis of getting permission from DIMIA.(58)

(c) Responsibility and powers of State child protection agencies in detention centres

While State child protection authorities have the power to enter a detention centre to investigate a child abuse notification, they have no power to enforce their recommendations as the Department retains ultimate authority in detention centres.

The nature of Australia's federal legal system is that Commonwealth legislation will prevail over State legislation.(59) In the context of child protection in immigration detention centres this means that the Migration Act, which requires that children remain in detention, will prevail over State child protection legislation which otherwise grants power to child protection authorities to recommend that a child be removed from detention. The Flood Report noted this problem in February 2001 and recommended that:

a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) between [the Department] and each of the state authorities be established to clarify the roles and responsibilities of each party in cases where the state authorities make strong recommendations that a child be removed from a centre.(60)

In December 2001, the Department entered a Memorandum of Understanding relating to Child Protection Notifications and Child Welfare Issues (the 2001 MOU) with DHS which aims to:

Ensure appropriate notification and referral of all cases of possible child abuse or neglect which occur at places of immigration detention in South Australia.(61)

The 2001 MOU emphasised that although DHS has the responsibility to investigate child abuse allegations it has no authority to implement those recommendations of its own accord:

DHS has a legal responsibility to investigate child protection concerns for children in immigration detention in South Australia. However, any interventions undertaken to secure the care and protection of detainees must be actioned by DIMIA. DIMIA will consider carefully DHS recommendations to ensure that the best interests of the child are protected.(62)

The Department has also observed that neither State courts nor State government officials have any jurisdiction to order the release of a child from immigration detention:

A State government or court cannot order the release of a child detainee from immigration detention pursuant to State child welfare legislation. Any State child welfare legislation which purported to authorise a State Minister or official, or a court, to order the release of a child, would be inconsistent with the provisions of the Migration Act 1958 (Migration Act) which clearly require the keeping in immigration detention of all unlawful non-citizens, including children.(63)

DHS outlines the following powers of the South Australian Children's Protection Act, which would normally be used to protect children in the community, but 'are directly inconsistent with the detention requirements of the Migration Act and therefore cannot be applied':

- The power of the [South Australian] Minister to enter into a voluntary custody agreement with the guardians of the child;

- The power to remove a child from a place ...;

- The authority of the Youth Court to grant custody of a child to the [SA] Minister ...;

- The authority of the Youth Court to direct a person who resides with a child to cease or refrain from residing in the same premises as the child ...;

- The ability of an employee of the [DHS] to take a child to such persons or places as the Chief Executive Officer may authorise ...;

- Orders the Youth Court may make granting Custody or Guardianship of the child to the [SA] Minister on a long term basis and associated ancillary orders.(64)

Negotiations of MOUs with Western Australia, Victoria and New South Wales agencies are still underway; however, it appears that those agreements will work with similar limitations. The Western Australian Government has already expressed concern about its lack of authority to implement recommendations:

The Western Australian Government welcomes the progress being made on the MOU relating to child protection. It is concerned, however, about the discrepancy between DCD's statutory responsibility for child protection and its lack of authority within detention centres.(65)

Some of the practical difficulties that arise as a result of the unenforceability of the State child protection authority recommendations for removal of children are illustrated in the case study at the end of this chapter. This issue is discussed in further detail in Chapter 9 on Mental Health.

8.2.4 Federal and State police

The Australian Federal Police Act 1979 (Cth) provides that investigations of criminal matters on Commonwealth land are a matter of agreement between the State and Federal Commissioners of Police.(66) A February 2001 report commissioned by the Department regarding the breakouts in Woomera, Port Hedland and Curtin detention facilities in mid 2000, commented on the need to clarify the 'jurisdiction, responsibilities, roles, resource capabilities and protocols' regarding each of the relevant authorities, including State police.(67) The February 2001 Flood Report also urged the Department to enter memoranda of understanding that:

clearly and unambiguously articulate[s] the role of the state police in any incidents at Commonwealth detention facilities which may require police involvement.(68)

To the Inquiry's knowledge no such agreement has been reached with any State police authority. However, staff from DHS note that in South Australia it is the role of the State police to investigate abuse by anyone other than the family and it is the role of the Federal Police to investigate any allegations against ACM or Department staff.(69)

8.3 What exposure have children had to riots, violence and self-harm in detention centres?

Immigration detention centres have been the site of a number of major disturbances including demonstrations, hunger strikes, attempted and actual self-harm, riots and fires. It is clear to the Inquiry that the detention of children within this environment has meant that they have been exposed to a level of violence and distress that is unlikely to have occurred in the community.

In early 2003 a psychiatric study regarding children detained in a remote centre noted the impact on children of the exposure to violence:

All families described traumatic experiences in detention, such as witnessing riots, detainees fighting each other, fire breakouts, detainees self-harming, and witnessing suicide attempts. It should be noted that the researchers could not verify independently allegations made by asylum seekers particularly those directed at detention officers. ... The children particularly reported being distressed by witnessing the frequent acts of self-harm and suicide by other detainees. All of the children witnessed the same act of self-harm by an adult detainee who repeatedly mutilated himself with a razor in the main compound of the detention centre. Children also described having witnessed detainees who had slashed their wrists, jumped from buildings, resulting in broken legs, and detainees attempting to strangle or hang themselves with electric cords. At times, children witnessed their parents suicide attempts, or saw their parents hit with batons by officers. A number also witnessed their friends and siblings harm themselves. ... A number of families reported enforced periods of separation from each other during detention (7 families), often when a parent was taken to solitary confinement either as punishment or in response to self-harm attempts.(70)

The submission from the Conference of Leaders of Religious Institutes includes a discussion with mothers who describe how frightening it was for children at Maribyrnong to be near a riot:

There was a riot of sorts and several men damaged equipment such as computers, televisions and other furniture. This happened at night and was accompanied by a great deal of noise ... The mothers [told] me later, how afraid the children and they had been, as they were locked up [in] their own area just next to the area where it was all happening (in the same building). They were powerless to reassure the children that they were safe as they really were very afraid themselves, not knowing what was really happening, whether the place would be burned down, if the violence would escalate and overflow into their area.(71)

Dr Annie Sparrow, who was employed at Woomera for four weeks, two of which were in January 2002, described the surrounding violence as follows:

children are exposed to the acts of violence, as it were, that occur between the guards and the detainees or by the adult detainees or even the children, of self-mutilation or self-harm or violent behaviour when the adults would climb on to a building and threaten to throw themselves off or actually injure themself on wire ... And again, that is not conducive to any child's mental health where ever they are.(72)

Some of the self-harm incidents that children witnessed were quite dramatic. For example, children have seen their male relatives throwing themselves on razor wire, causing multiple lacerations to their bodies. A former ACM staff member described an incident where one group of children witnessed self-harm by another group of children:

I was in a room at [Woomera detention centre] with about 30 or 40 children watching a video when a group of about 10-15 unaccompanied minors formed in a group outside. They had taken their shirts off and proceeded to slash their chests with razor blades. They were all covered in blood. A number of the children saw this and some went outside to where this was taking place.(73)

One of the disturbing consequences of being exposed to violent behaviour is that children are drawn into it - themselves participating in acts of self-harm and violence, thereby seriously risking their safety and well-being and compromising their psychological health. Such behaviour has included children sewing their own lips together.

8.3.1 Chronology of riots and other major disturbances

The Department's incident trend analysis gives some indication of the prevalence of major incidents (an incident that 'seriously affects the good order and security of the detention centre') in detention centres.(74)For example, between July and December 2001 there were 688 major incidents involving 1149 detainees across all detention centres.(75) Of those incidents, 321 were alleged, actual or attempted assaults (19 of which involved children, 9 of which involved alleged detainee assaults on staff), 174 were self-harm incidents (25 of which involved children) and about 30 per cent involved 'contraband, damage to property, disturbances, escapes and protests'.(76) Seventy-four per cent of all the major incidents in that period occurred in the Curtin, Port Hedland and Woomera centres, where the largest number of children have been detained for the longest periods of time.

From January to June 2002, there were 760 major incidents involving 3030 detainees across all detention centres.(77) There were 116 alleged, attempted or actual assaults (16 of which involved children, 13 of which involved alleged detainee assaults on staff), 248 self-harm incidents (25 of which involved children) and 52 per cent of incidents involved 'contraband, damage to property, disturbances, escapes and protests'.(78) Almost 80 per cent of all incidents occurred in Curtin, Port Hedland and Woomera.

The following table, sourced primarily from media reports, sets out a rough chronology of the major disturbances in the three most problematic centres between July 1999 and December 2002.

Some of the disturbances listed below were over fairly quickly, for instance riots rarely lasted more than a day. Others, like protests and hunger strikes, could last weeks. Some disturbances involved all compounds in the centre and others were restricted to one or two compounds. The approximate numbers of detainees involved in the incidents are included where the media or other sources have reported them.(79)

The chronology is intended to give some sense of the environment in which the majority of children in immigration detention were living, rather than to provide a comprehensive description of each and every occurrence in the detention centres.

Chronology of major disturbances |

|||

| Date | Woomera | Curtin | Port Hedland |

|---|---|---|---|

| July 1999 | [Not open] | [Not open] | Riot and escapes. |

| Aug 1999 | [Not open] | [Not open] | Protests. |

| Mar 2000 | Demonstrations. | ||

| June 2000 | Two days of protests. Approx 480 detainees walk into town. | ||

| Aug 2000 | Three days of riots and fires. Tear gas and water cannons used. 60-80 detainees involved | ||

| Nov 2000 | Hunger strike by more than 30 detainees. Some forcibly fed in hospital. | ||

| Jan 2001 | Riot involving approx 300 detainees. | Riot involving approx 180 detainees, hunger strike. | |

| Mar 2001 | Riot. | ||

| April 2001 | Riots and fires, tear gas used, approx 200 detainees involved. | ||

| May 2001 | Riot. | Riot, hunger strike, tear gas used. | |

| June 2001 | Riot and confrontation between ACM and approx 150 detainees. Injuries on both sides. Water cannon used. | Riot. | |

| Aug 2001 | Riot, fires, tear gas, self-harm. Centre on riot alert for more than a week. | ||

| Sept 2001 | Protest outside. Water cannons and tear gas used on detainees inside. | ||

| Nov 2001 | Riot and extensive fires. Approx 250 detainees involved. | ||

| Dec 2001 | Three separate riots, each with fires. Tear gas and water cannons used. | ||

| Jan 2002 | Hunger strikes, lip-sewing, including seven children. | Hunger strikes, lip-sewing. | Hunger strikes, lip-sewing. |

| Mar-Apr 2002 | Riots over the Easter period. Approx 50 escapes including mother and three children. | Riots and fires. Approx 150 detainees involved. Tear gas used. Family compound created after these riots. | Riot involving approx 150 detainees. |

| June 2002 | Hunger strikes, including 13 children. Escapes, including three children. | ||

| July 2002 | Riots and fires. | ||

| Dec 2002 | Extensive fires. | [Not open] | One fire. |

The following sections describe just a few of these events.

8.3.2 Major disturbances at Woomera

Woomera opened in November 1999. Woomera has been the site of more riots and unrest than any other centre, as the above chronology shows. While the number of physical injuries sustained by children during these disturbances was few, the psychological impact they left on children was substantial.

In such a relatively small environment, children are inevitably exposed to whatever crises, riots or violence occur. One father said of children at Woomera: 'they know everything - who cut themselves, who try to hang themselves'.(80)

The two major disturbances about which the Inquiry has the most evidence are those that occurred in January and April 2002. However, when the Inquiry spoke to families in January 2002, it became clear that other events, such as the fires in November 2001 and December 2001, had a negative impact on the children who had witnessed them. There were 359 and 322 children detained in Woomera in November and December 2001 respectively.(81)

For example, an 11-year-old child told an ACM psychologist in December 2001 that he had cut his arms and legs with a razor blade because he was tired and because he had been in the centre a year and all his friends had left.(82)

Another family told the Inquiry that they were housed in a donga (demountable sleeping quarters) beside one of the buildings that was burned in November 2001. During the fires, the children, two young girls, had to remove their belongings from the room because they thought that they would be destroyed by fire. Detainees, including children were left inside the compounds with the fire while it burned. The two girls stood outside their donga and watched nearby buildings burn. The parents said that the girls still asked about the fire and one shook with fright at night time.

One of the girls saw the hunger strikers and witnessed a man jumping onto razor wire. She saw his bloodied body afterwards. The girl's parents say that she asks about this man all the time and that their children ask them 'why don't they eat?' and 'why is this happening?' They have no answers for them.(83)

(a) Woomera - January 2002

In January 2002, when there were 281 children detained at Woomera,(84) there was a major hunger strike and protest, which included lip-sewing, involving a large number of detainees. Seven children were involved in the lip-sewing. Many other children were living amongst and observing the ongoing protests.

(i) Hunger strike

The hunger strikes began in response to the Department halting the processing of visa applications by Afghan asylum seekers.

The ACM Manager reported that Woomera had been relatively calm until 11 January 2002, when the Refugee Review Tribunal reportedly refused to grant a visa to an Afghan applicant on the grounds that the Taliban was no longer in power in Afghanistan. While there were a few incidents in the following days, the hunger strike proper began on 16 January 2002.

When Inquiry officers visited Woomera between 25 and 29 January 2002, they observed:

- hunger strikers, including a man being removed by stretcher from the Main Compound;

- people with lips sewn together;

- the aftermath of a man jumping onto razor wire;

- demonstrations (people climbing onto the top of dongas and calling out for freedom, people dragging mattresses and bedding into the compounds);

- an extremely distressed woman screaming hysterically for an extended period, apparently after a dispute with an ACM officer;

- actual and threatened self-harm; and

- smashing of windows.

All of these events took place in full view of children, apart from the smashing of windows, which they may have heard.

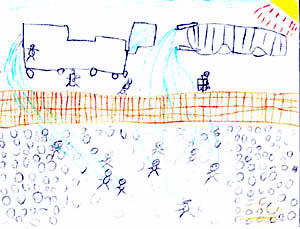

Hunger strike at Woomera, January 2002.

The Inquiry observed generally that the centre had an atmosphere of despair that affected every aspect of life. It was an atmosphere into which children were inevitably drawn.

At the time of the Inquiry's visit, there were hunger strikers in all of the compounds, with most based in the Main Compound. Hunger strikers had removed the bedding from their dongas and were lying on mattresses around internal perimeter fences of the compounds, using blankets fastened to fences as a form of shelter. In the Main Compound, women who were hunger striking congregated under a set of children's play equipment. The hunger strikers were being monitored by health staff to identify when medical attention was necessary.

Children were moving freely around the hunger strikers, even playing alongside them. A staff member employed at Woomera for 12 months at the time recalls:

I found the mass hunger strike extremely disturbing, people dragged their mattresses out into the open, and some people had stitched lips. I called it 'The Field of Mattresses', because put simply that is what it was. Bodies littered the ground in all compounds, I remember feeling the strangeness of the situation one day as I was making my way to the medical centre, just inches away from my feet through the wire, people lay lifeless on mattresses in the searing desert heat. Management had lost control of the centre.

It was a few days into the 'Field of Mattresses' about 10.00am when I entered the main compound [of Woomera detention centre] with a colleague ... to open a recreation building. We decided to check on a group of about 20 women who had joined the hunger strike, and had based themselves in the playground. What we found was an appalling tragedy.

A group of at least a dozen women, predominantly Afghanis, some Iranians and Iraqi women. This in itself was unusual as the groups do not often mix, this indicated to me the seriousness of the situation, and was a clear show of unity and support for each other.

The playground floor was littered with mattresses, some women laying, others sitting, some children bouncing on mattresses. I recognised most of the children as long term minors. [My colleague] and I asked each mother and child if the children were drinking and eating. The mothers and children confirmed the children were eating. A young woman I attended had a crawling baby with her; the baby appeared confused and dishevelled and tried to get the mother's attention by crawling all over her. I looked directly into the mother's face and noticed she was disoriented and appeared confused. When questioned she nodded she had not been eating, I asked her twice if she was feeding her baby she nodded yes and held her breast, indicating she had been breast feeding the child which other women present confirmed. The young mother's eyes were blank, unfocussed and held no life.(85)

ACM reports show that on 20 January 2002, there were 37 children on hunger strike.(86) Fifteen unaccompanied children had commenced the hunger strike the day before.(87) By 22 January, the total number had decreased to 31 children(88) and eight unaccompanied children (possibly some of the other children as well) were on a 'partial' hunger strike:

Detention manager reported that even though all UAM's are reported to be on hunger strike, they are drinking eight cups of water each per day with sugar in it.(89)

Two unaccompanied children swallowed shampoo and disinfectant respectively during this time.(90) FAYS were updated on the progress of these children on a daily basis.(91) Medical incident reports confirm that children of concern were being checked.

There have been suggestions that parents encouraged their children to go on hunger strike. Detainees interviewed at Woomera responded as follows:

I totally disagree because this is not fact. This man [a hunger striker], his children if not eat he will get angry with them. ... This is very misunderstood because the outside Australian public say they make children [do it] but this is really unfair to guys like that. When the woman, children and the father and mother is very depressed and these children themselves are still the same, they are not happy to eat and those people who stitch their lips - this is the boys' decision, believe me that's the boys'. As you see yesterday they started to remove the stitch.(92)

The claim [that children are being coerced into hunger striking and lip-stitching] is totally baseless. ... We are human beings, we don't use our children. We are ready to sacrifice ourselves for the sake of our children.(93)

The Department highlighted a case where a father refused to allow his hunger-striking son to be taken to the medical centre. However, this objection was short lived and the detainee delegates worked with ACM staff to make sure that all children could be treated.(94)

The Department also highlights that families who were not on hunger strike were given an opportunity to move to another compound and several took up that offer.(95)ACM, on the other hand, highlights that 'design limitations' make it very difficult to shelter children from being exposed to such activity, given that 'behaviour of this type was not predicted at the time the facility was designed'.(96)

Nevertheless, ACM detention staff tried to move the unaccompanied children from the compound where the primary hunger strike was taking place 'and put them all together so that they could all look after each other'.(97) Unfortunately, as set out above, this does not appear to have prevented unaccompanied children from participating in the hunger strike. However, two unaccompanied siblings were taken out of the centre altogether, to the Woomera Housing Project. They had expressed some fear of being attacked by residents unless they stopped eating.(98)

The Inquiry accepts that there are practical difficulties in sheltering children from the protests conducted by other detainees within the closed environment. This highlights the risks of keeping children in immigration detention.

(ii) Lip-sewing

Seven boys went beyond hunger striking and participated in the protests by sewing up their lips. Three were twelve-years-old (one of whom was an unaccompanied child), two were 14-years-old, one 15-years-old and another 16-years-old.(99) Four of the children had been detained for 12 months at the time they sewed their lips, and three for 6 months.

When ACM staff discovered that the children had sewn their lips together they were placed on two-hourly observations and offered food, water and medical attention.(100)Staff also notified FAYS, the South Australian Police and Glenside Psychiatric Hospital.

All children had their stitches removed within a day of putting them in, either at Woomera Hospital or the on-site medical centre. The records indicate two of the children stitched their lips a second time, and a third child may also have done so. All the children who sewed their lips were also participating in the hunger strike, even though in some cases it was possible to eat with the stitches in.

The mother of two of the boys who sewed their lips was also on hunger strike. The eldest son stitched his mouth twice, slashed the word 'freedom' down one arm and slashed his other arm and torso. This family was closely observed throughout the hunger strike.(101) One staff member in particular recounts her observations and efforts:

As I moved around the group I came to [the mother], an Afghani woman well known to myself and several of my colleagues. I had worked extensively with her five children aged 14 years to 5 years. I had filed numerous reports and referrals on the family, particularly the oldest child. ...

I was not surprised to see [the mother] joining the protest as she and her children had at that stage, been held in detention for over 12 months. I was alarmed at [her] condition. She lay on a mattress too weak to sit up; I knelt beside her, the other women told me she had not eaten for days. [Her] lips were stitched from corner to corner (this is a sight I will never forget), her eyes also held no life. I placed my hand on hers and cried, when I looked up all present were crying including [my colleague]. ...

I returned to the office to collect some recreation items for [the oldest son, in hospital] and left immediately for the Woomera hospital. As I crossed the Administration compound to exit the centre, I looked into the main compound and noticed [the mother] being physically supported by her [younger son] making their way back towards their room. It was [a] pitiful sight, the boy's head was hung low bearing the weight of his mother, who was barely able to move one foot in front of the other.

At the hospital a nurse who had been caring for [the boy] spoke to me for about ten minutes. She informed me [that the brothers] had both presented earlier in the week with stitched lips and had been brought to the hospital to have the stitches removed. She also told me that [the younger boy] was extremely distressed by the situation.

When I saw [the older boy] he was visibly happy to see me. He smiled, he was clean and well groomed. He told me he liked the hospital and it was better than the camp. [He] was very happy with his brother's 'Salaam' message. I gave the boy the pencils, paper and picture books I had brought for him, then we talked about his artistic talent and how he could use the picture books to copy some drawings.

[His] happiness at my visit was in stark contrast to what I saw, his lips were unstitched but he had slash marks on both his outer forearms, the scars from his previous slashing not long healed. The word freedom had been cut

into the length of one of his inner forearms, when I questioned him about this he just shrugged his shoulders and said nothing and became quiet.(102)

The Inquiry investigated allegations that adults were involved in the sewing of children's lips. Former staff, including doctors, psychologists, nurses and recreation officers, were questioned at hearings,(103) as were child protection authorities and current detention staff at Woomera. All were of the view that there was no evidence to support the suggestion that adults were involved in sewing children's lips. For example, the Department's Manager at Woomera told the Inquiry that there was no evidence that parents had sewed their children's lips, and that the children had admitted that they did it themselves. The ACM Health Services Coordinator also said that the children had acted independently.

During the Inquiry's public hearing, a senior Departmental officer said, 'it is my understanding that we were subsequently advised that there was no evidence either to confirm or deny' that parents were involved in sewing the lips of their children.(104)

A refugee mother who had been detained at Woomera in January 2002 told the Inquiry:

No, the families didn't encourage the children to do that, but only the children did that by themselves. They used to gather and shout, 'Freedom!' and still our children, up until now at home, they will still call, 'Freedom! Freedom!'(105)

A FAYS report of 24 January 2002 notes several children stating that they sewed their lips themselves.(106) They stressed, however, that Woomera was a coercive environment for all people detained there and that children were vulnerable because of this environment. Moreover, children may have been copying the behaviour of the adults around them. FAYS also noted their concern that where the parents were 'becoming decidedly weaker they are unable to protect and supervise their children'.(107)

The ACM psychologist at Woomera from October 2000 to December 2001, Harold Bilboe, made similar observations with respect to lip-sewing incidents that had occurred on a previous occasion:

Amongst the self-harm that occurred while I was at [Woomera], there was lip stitching amongst adolescents. There was no evidence of which I was aware to suggest the involvement of parents or adults in the stitching of children's lips. The only time I heard of these allegations of the involvement of adults in stitching the lips of children was from the Minister for Immigration.(108)

Another psychologist who worked in Woomera at this time told the Inquiry that she believed that a child may have had assistance in sewing his lips, but that the child's mother would have been unlikely to have provided this assistance herself:

I don't think she would do it to him but I think he would have had help because it is such a difficult thing to do and I think if any child - I mean, he is so emboldened now that he would want it done ... I'm sure he would have been assisted but he would have asked or demanded it to be done to him, that boy. Now, with others I don't know, but I don't think they could do it.(109)

This witness said that she could not say with any certainty that this child had been assisted.

Dr Jon Jureidini, a psychiatrist who has worked with children in immigration detention, told the Inquiry that he had never heard of parents encouraging their children to self-harm:

I have no experience either first hand or in literature of parents deliberately encouraging their children to self-harm. I certainly think that parents can play a role in a number of other ways. First, that as individual adults self-harming themselves is providing that model for children, wittingly or unwittingly. Also the incapacity of parents to provide ordinary safety and protection for their children which is not a criticism of the parents themselves but symptomatic of the fact that they are overwhelmed in that environment.(110)

The Western Australian Government also confirmed that parents had no involvement in lip-sewing by children at Port Hedland:

We recently had a referral in relation to self-harm, where there was an allegation that parents were involved. The outcome of our assessment, and the children themselves, who were young people, were very clear, that they made the decisions themselves, their parents were not involved in that decision.(111)

(b) Woomera - Easter 2002

Extensive riots occurred at Woomera during Easter 2002. The disturbance was precipitated by a protest outside the centre and resulted in the escape of approximately 50 detainees.(112)

The Department and ACM knew that an Easter protest was being planned by people opposed to the mandatory detention of asylum seekers back in January 2002.(113)On 25 March 2002, a meeting between ACM, the Department, the South Australian Police, the Federal Police, the Woomera Area Administrator and Woomera Hospital, amongst others, was convened in order to discuss a strategy to deal with the protests. ACM planned to have extra staff on site, and the South Australian and Federal police had arranged for staff to be present. ACM Centre Emergency Response Teams (CERT) began training for the protest and compounds were searched to try and remove objects that could be used as weapons.(114) A barbeque was arranged for detainees in all compounds as a 'diversionary' tactic, but was cancelled when detainees indicated that they would not participate.(115)

The ACM incident reports indicate that approximately 800 protesters participated in demonstrations outside the Woomera fences. The protests started on 29 March 2002 and ended on 1 April 2002. Amongst other occurrences, detainees climbed on the rooves of dongas, waved banners and shouted chants of freedom. Some children climbed onto rooves with their parents, although they were quickly convinced to come down from the roof.(116) Some detainees threatened to set themselves on fire if detention staff did not leave the compounds.(117) Internal and external fences were brought down and some detainees used the dismantled fencing, bricks and rocks as weapons. Tear gas was deployed on four different occasions when staff felt threatened by detainees.(118) Water cannons were also used to subdue detainees and stop escapes.(119) There were also some instances in which ACM officers used pieces of fencing and rocks as weapons in exchanges with detainees, a practice not condoned by ACM management. The disturbances continued through the day and night. Seventeen staff and 14 detainees were treated for minor injuries.(120)

Father Frank Brennan was visiting Woomera at the time of the riots. He described what he saw and heard on Good Friday night, 29 March 2002:

Inside [Woomera], during the riot and breakout, I spent two hours with men, women and children who had come from church and who were unable to return to their accommodation and unable to find sanctuary in an alternative compound because they were threatened by another detainee disturbed by their religious practices. That detainee was finally apprehended by half a dozen ACM officers in full riot gear backed by a water cannon truck which had been moved into position. Meanwhile two other detainees were on the roof threatening self-harm exacerbating a situation of mass hysteria. Children in my midst were highly traumatized. One child remonstrated with his mother saying he should attack an ACM officer because that is the only way that you get a visa!(121)

ACM incident reports confirm Father Brennan's report that the Christian detainees could not be moved to a quieter compound because of threats from others.(122)However, the incident reports do not mention any alternative measures taken to shelter Christian or other children from these violent events.

Video evidence of the Easter riots at Woomera reveal that while some children were actively participating in the riots, others were highly distressed by what was going on around them. For example, a girl separated from her family was taped standing outside the sterile zone and screaming continuously. The tape also shows children being hosed:

Children, from approx 8-10 years old, can be seen mixing with adult detainees in the sterile zone and collecting objects. Detainees approach ACM detention officers again, and 4 boys can be seen at the front. Their ages seem to range from about 7 to 14 years. ACM detention officers use a water hose on the detainees to move them back. Water pressure is not high.(123)

There is no suggestion in ACM's incident reports that any children were injured in the riots. However, the Inquiry heard an allegation that a child was hit with a baton. That allegation was brought to the attention of the police. The police found that as the alleged offenders could not be identified there was insufficient evidence to continue its investigation. The mother of the child also lodged a human rights complaint with the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission (the Commission). The Commission's Complaints Handling Unit heard evidence regarding this allegation, and allegations regarding the manner in which tear gas was used while children were present, in a public hearing on 9 and 10 July 2003. The Commission found a breach of human rights in relation to this complaint. The Commission's report was tabled in Parliament in March 2004.(124)

The psychological impact of this overall disturbance on children became very clear to the Inquiry. Nearly all families interviewed at Woomera in June 2002 also told the Inquiry that searches and headcounts during the riots had frightened their children:

That night, say 4 o'clock am they came. I thought it was a head count, they woke the, they wanted to wake them up and just count them. ... And they woke [my three year old] up and he, he started to scream you know wildly. ... Like a sheep they put us all, all of us in the Mess and they closed the door.(125)

The father of a young girl told the Inquiry:

At Easter there were guards in riot gear and at midnight they went barging into the dongas abusing people verbally and shaking their batons. This has caused [my daughter] to have bad dreams. The Easter experience was enough trauma for a lifetime.(126)

A teenage girl recalled the event as follows:

4.00 am and then after the checking we showed them our I.D. card and it was 6.00 am and then we came back you know to our room. Yes it was 6.00 am you know. They searched our room you know, they broke a lot of things and they broke the flower pot off a rose and it was just like a - you felt there was an earthquake in the room. And even they just pulled on the curtain because they look, it seems to me they were very angry.(127)

The Department's Manager at Woomera made some general comments regarding the riots in his report of March 2002, but did not specifically mention the involvement or impact on children. He reported the event as follows:

A number of complaints about use of gas and allegations of assault made following action to regain control of the compounds following the demonstration on Good Friday - these are being followed up.(128)

In the April 2002 Manager's report there was discussion of an incident relating to one child.(129)

8.3.3 Major disturbances at Curtin

Although there were several major disturbances at Curtin during the three years it was open, the Inquiry received the most information about a riot that occurred during April 2002, when 43 children were detained there.(130)

There had been some unrest in the centre for the 10 days preceding these riots, including damage to property and self-harm. The incident report concerning this riot describes the genesis of the violence on the evening of 19 April 2002, as follows:

At approximately 19.14hrs two detainees who were previously identified having committing offences over the last week, were asked to move to India compound. In case they refused the mess was secured, and a team of CERT equipped officers entered the mess via the rear door. [The two detainees] were asked to move they refused and so were held by the officers. The two detainees resisted and other detainees began obstructing the officers.

Officers then removed [one of the detainees] to the rear of the mess however [the other detainee] had armed himself with a broken fluoro tube and threatened [the officer who] then protected himself and disarmed [the detainee] by hitting [him] with his baton on the left thigh and right forearm. During this time a large number of detainees began throwing projectiles at the CERT team in the mess at the same time a relief CERT team than [sic] had entered the compound to assist in the extraction of detainees was also attacked by detainees throwing projectiles.(131)

The violence spread throughout the centre and by the next morning the dining hall, kitchen, food store rooms, recreation and welfare areas and computer rooms had been severely damaged.(132) Looting and vandalism was occurring. Two 'pressure pack tear gas dispensers' were discharged accidentally when projectiles hit them and five tear gas dispensers and one gas grenade were let off when officers felt under threat.(133)

The next day eight family groups, nine single men, one single female, eight female children and eight male children moved to the Echo Compound which was quiet. Approximately 50 other single male detainees requested to move the following day.(134) On 21 April ACM reports that other families were given the opportunity to move. It was ACM's view that some refused because they had been involved in the looting and were hiding contraband.(135) A boy with cerebral palsy was moved to the local hospital on the evening of 19 April to keep him safe from the unrest.(136)

Over the next couple of days small fires were being lit, without extensive damage, and detention staff were negotiating with detainees to hand in their makeshift weapons. By 24 April the centre began returning to a more normal routine.(137)

The Inquiry interviewed 13 family groups when it visited Curtin in June 2003, ten of whom mentioned the impact of the April riots and two of whom spoke about the impact of riots generally. One parent who was in the mess hall described the following sequence of events:

All of a sudden they closed three entry doors or gates to the canteen and about 20 people, all huge, and wearing uniform and wearing glasses and everything came in and the situation was really frightening and intimidating.(138)

Another detainee reported that she had tried to protect three young children who were in the mess with her:

There were three some younger children in the canteen and I remember that I grabbed three younger girls and I put them on my lap and I was just trying to comfort them because they were really frightened and they were screaming. One of these children who was in my arms screamed and screamed so much that then she couldn't control herself and she wet herself.(139)

All ten families who discussed the April riot spoke of the problems their children had after this disturbance, for example nightmares, and bed-wetting. One mother said that:

Basically that incident really psychologically affected my daughter and after that she is telling me to go back and prepare ourselves to be killed by people in there so she says that she prefers to go back and die than stay here in this country. We took refuge in this country because of the injustice that we have in our own country but now we see that the situation in here is even worse. ... The fact and reality is not what they told you, although I don't know what they've told you about this incident. Please believe us we are not terrorists, we're not criminals in here. We have just come here to save our lives.(140)

A father told the Inquiry why the violence in the centre made him afraid for his children:

Unfortunately it's a very dangerous situation for our children because when the violence is starting and the people are starting to do the bad things around the camp our children are involved in it. They are in the middle even if they are not doing anything and it is very dangerous for their life. They might, you know, might get killed or they might get danger accident because they are in the middle of the crisis. They cannot separate themselves.(141)

Both ACM and the Department deny that children were in the mess hall when the April riots broke out. It is unnecessary to come to any concluded view on this issue as it is clear to the Inquiry that children were caught amongst, and negatively impacted by, the general violence that occurred throughout the four day disturbance.

Following the April riot, families were offered accommodation in a compound away from single men. The Department Manager reports:

A positive is that families, and a few single males who were in fear, were offered a move into a secure compound, Echo. The families that took up the offer appear to feel very safe and are very happy being away from single males and those they view as trouble makers.(142)

8.3.4 Efforts to protect children during riots

As the above descriptions demonstrate, children are at increased risk of physical and emotional damage by virtue of their detention in an environment in which such violent events occur. While the most obvious measure to reduce or eliminate such risks to children is to remove them from that environment altogether, it is nevertheless important to examine what measures were taken to protect children while in detention.

The Department's contract with ACM places the primary responsibility of maintaining security in the detention centres on ACM. ACM, however, told the Inquiry of several constraints on its ability to fulfil that function.

First, ACM states that a number of factors which impacted upon security were beyond its control. ACM argues that it was largely powerless to prevent riots because they were, 'without exception', detainee protests against the government's immigration policy and ACM did not have the relevant 'negotiating currency' of visas.(143) ACM also suggests that protesters outside detention centres and media attention had a role to play in encouraging disturbances.(144) ACM further claims that reluctance by the Australian Federal Police to investigate and prosecute detainees who were involved in violence contributed to a sense of impunity.(145) A February 2001 consultant's report examining the breakouts in Woomera, Port Hedland and Curtin in mid-2000 also suggests that:

The cumulative effect of delays in the visa determination process, the basic living conditions, the inhospitable environment and the influence of agitators was a high degree of unrest amongst the detainee population.(146)

Second, ACM states that the 'infrastructure' and 'design limitations' of Woomera and Curtin in particular, limited its ability to contain major demonstrations and protect children from the violence.(147) The February 2001 consultant's report on security measures confirms that the infrastructure made it difficult to contain major disturbances, although does not seem to specifically address the impact on children.(148)

Third, both ACM and the Department suggest that the reasons some children were exposed to violence was that parents failed to execute their 'duty of care' towards their children.

It is outside the scope of the Inquiry to investigate the causes of the riots and the Inquiry therefore makes no findings as to whether or not they could have been prevented.(149) However, the second and third points are discussed in further detail below.

(a) Procedures to shield children from violence during riots in detention centres

The Inquiry accepts that when children are detained within a closed environment, the options available to shelter children from those events are necessarily limited. The question is, however, what steps were taken to minimise the impact of riots on children within that context.

The Department suggests that all parents are encouraged to protect their children and that 'all detainees who volunteer are moved from the danger and relocated to safe areas within the centre to ensure their safety and protection during a disturbance'.(150) However, the evidence before the Inquiry suggests that it was not always possible for families to move to a safe area.

There is some evidence indicating that when there was some prior warning of disturbances, or when the disturbances stretched out over some time, families were offered the opportunity to move from what were likely to be the most troublesome compounds. However, sometimes a 'lock-down' procedure was used during a crisis in order to try and contain the violence. One of the consequences of this procedure was that sometimes children were trapped within the melee.

The South Australian child protection authority comments on the impact of the 'lock-down' procedure on the safety of children during critical incidents in Woomera:

Whenever there is a disturbance of some kind in the compound, the initial response appears to be that ACM staff withdraw until a designated officer attends to manage the incident. Staff will remove themselves from the compound in question and all free movement around the centre (external to the buildings) is prohibited. Detainees in other compounds cannot leave that area until the situation is resolved.

This management plan effectively locks the detainees into the compound with 'the problem' - that is, persons not involved in the incident are left to manage their own safety. This response leaves children exposed to the sight and/or sound of the incident, be it a distressed adult or destruction of property or a riot.

The aim of this form of management appears to be to defuse the incident and protect staff from injury. The procedure, though, does not protect the children. If the parents fail to shield their children by removing them to a safer area, there is no mechanism by which the centre will step in and do this. The duty of care to the children is, in effect, non-existent in such situations.(151)

A former ACM Operations Manager also spoke of problems that arose during a 'lock-down' despite the efforts of ACM staff to protect children:

I was very concerned about children's safety when there were riots and disturbances. When there was a riot, the centre was locked down and kids were in the thick of it. It was difficult to get children out because parents often did not want to be separated from them. Staff, particularly nurses, tried their best to keep children safe.(152)