Native Title Report 2007: Chapter 7

Native Title Report 2007

Chapter 7

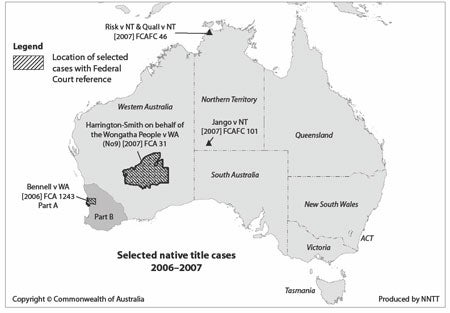

Selected native title cases: 2006-2007

- Jango v Nortern Territory

- Bennell v Western Australia

- Risk v Northern Territory

- Harrington-Smith on behalf of the Wongatha People v WA

The Yankunytjatjara and Pitjantjatjara and other Indigenous people of the town of Yulara, in the shadows of Uluru, had their claim for compensation for extinguishment of native title rejected by Justice Sackville in the Federal Court (the Jango case)1in 2006. The Noongar people (the Noongar case)2 had their claim for native title over the metropolitan area of Perth upheld. Further north, around Darwin, the Larrakia people (the Larrakia case)3 learned that the common law would not recognise their native title when Justice Mansfied handed down his decision.

Out in the desert and mineral rich areas of the nation, in the Goldfields of central Australia, the Wongatha people, in arguably one of the most complex native title cases yet heard by the Federal Court (the Wongatha case),4 heard that their claim was not properly authorised. After 100 hearing days and 17,000 pages of transcript, 12 years after they filed their first claim, they would have to start afresh.

These four cases5 exemplify just how far removed the reality of the operation of today’s native title system is from the intention of the Australian Parliament when it first passed the legislation. Each case highlights the hurdles faced by Indigenous peoples trying to use the native title system, established by the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) (the Native Title Act), to gain recognition of their rights and interests in country. Rights and interests that are held in accordance with their traditional laws and customs. Issues they highlight are:

- difficulties of obtaining compensation for extinguishment of native title;

- constraints imposed by the treatment of evidence and the rules of evidence;

- problems arising from the common law’s interpretation of the definition of native title in Section 223 of the Native Title Act, especially the requirement for a ‘society’ and substantial continuity of traditional laws and customs;

- hurdles that remain before practical access may be gained to native title, even after a determination recognising native title; and

- authorisation of a native title claim and the system’s capacity to identify issues early in the claim process.

These are only some of the issues arising from the interpretation of the Native Title Act by the common law. There is clearly a need to reassess the common law and, where appropriate, make legislative changes. The interpretation of the Native Title Act is placing almost insurmountable barriers in front of Indigenous people in their endeavours to gain recognition and protection of their native title.

Other Federal Court decisions

As well as the four decisions considered in this chapter, the Federal Court made 16 determinations of native title between July 2006 and June 2007.6 There were still 533 native title claimant applications in the system, at some stage between lodgement and resolution as at 30 June 2007.7

This chapter looks at the four cases mentioned above. The following chapter considers some common areas of concern that arise from these cases and makes some recommendations.

Jango v Northern Territory

The Jango case was the first trial for compensation under the Native Title Act.

Justice Sackville found that the claim for compensation for extinguishment of native title was unsuccessful on 31 March 2006.8 The claimants appealed to the Full Court of the Federal Court (three judges).9 The court dismissed the appeal on 6 July 2007 and upheld Justice Sackville’s decision.10

Two issues are important:

- compensation for extinguishment of native title: the case shows how difficult it is to obtain compensation under the Native Title Act. It identifies factors that are likely to be required for success in a litigated case; and

- evidence: native title proceedings exposed the difficulties imposed by Section 82 of the Native Title Act (the requirement that the rules of evidence apply) and by how the court treats expert evidence.11

Both of these are dealt with in a broader context in the next chapter.

The case

The applicants were six people who applied to the Federal Court for a determination entitling them to compensation for the extinguishment of native title. They applied on behalf of a group made up predominantly of Yankunytjatjara and Pitjantjatjara people (the compensation claim group). The primary respondents to the application were the Northern Territory and Australian governments.12

The applicants were seeking a determination they were entitled to compensation under the Native Title Act for the past extinguishment of their native title13 as a result of the construction of public works and the grant of freehold and leasehold interests over the town of Yulara (near Uluru in the Northern Territory). (I refer to the area over which compensation was claimed as the ‘compensation claim area’.)

The court held that to establish their right to compensation the applicants had to show they had native title rights and interests in the land just prior to the ‘compensation acts’ they claim extinguished their native title. Justice Sackville held that the claimants had failed to establish that, at the time the acts giving rise to compensation occurred (which he held to be in 1979), they were the native title holders for the land.14 He held they had not established the existence of native title rights prior to the acts extinguishing native title giving rise to compensation. The applicant’s claim for compensation, therefore, had to fail:15

Because no native title rights existed…the compensation acts had no effect on any rights, and no compensation became payable.

The applicant’s argued they were the native title holders. They argued they were members of a wider society identified by anthropologists as the Western Desert Cultural Bloc16 and that they held native title over the area through their acknowledgement and observation of Western Desert traditional laws and customs.17 The judge accepted the society of the applicants was the Western Desert Cultural Bloc. This was a society whose members observe a body of laws and customs, despite population shifts that may have taken place over time. However, the judge saw deficiencies in the presentation of the case.

The evidence supported the possibility that a smaller group of people could have rights over country on the basis of patrilineal descent. However, the broader claimant group before the court had not made out their case.

The broader claim group seeking compensation could not demonstrate observance of the laws about land that were contained in the pleadings for the case.18 Indeed, Justice Sackville said he had difficulty identifying a particular body of laws and customs that was consistently observed in recent times.19 The witnesses, in his opinion, ‘expressed very different views as to the content of the laws and customs that they recognised’.

The judge concluded that the traditional laws and customs of the Western Desert Cultural Bloc provided for small estate groups principally recruited on a patrilineal basis. The case put by the applicants did not emphasise patrilineal descent. The evidence before the judge showed differing views amongst Aboriginal people on the correct principles of recruitment. For these reasons the case fell short of showing that the contemporary laws and customs observed by people were traditional in the required sense.20

The judge considered that legally it was not open to him to find in favour of a smaller sub-group of claimants who could claim connection by patrilineal descent.

The Jango case prompted analysis of the relevant date at which extinguishment occurred, and therefore at which date the right to compensation accrued. Justice Sackville found that validation by the Native Title Act of prior extinguishing acts had the effect that extinguishment was taken to have occurred when the grant of the interest in land that extinguished native title was made (or the public work constructed). This was rather than when the legislation validating the prior extinguishing acts took effect (in the Northern Territory the validating legislation took effect in March 1994).

Is a determination of native title required?

Justice Sackville also considered the impact of Section 13(2) of the Native Title Act. Under that section if the court is making a determination of compensation and an approved determination of native title has not been made the court:21

… must also make a current determination of native title in relation to the whole or the part of the area, that is to say, a determination of native title as at the time at which the determination of compensation is being made.

Justice Sackville found a determination of whether native title existed was not required in the circumstances of a mere dismissal of the compensation claim. He therefore didn’t make one.

Claiming again?

The court made reference to the possibility that, while the compensation claim has been dismissed, had the case been pleaded differently, a different finding in relation to the existence of native title may have been made. As a result, the applicants had the option of re-shaping their case and attempting once more to have their rights recognised at common law.22

Appeal to the Full Federal Court

The case was appealed by the claimants to the Full Federal Court.23 The Full Federal Court dismissed the appeal, holding that Justice Sackville had not misunderstood the case, and that:24

The Court cannot, in hearing a native title determination application or a compensation application, conduct a roving inquiry into whether anybody, and if so who, held any and if so what native title rights and interests in the land and waters under consideration.

Compensation for extinguishment

Justice Sackville found that no native title rights and interests were held by the claim group before the court. Therefore, he did not need to consider whether compensation was payable. Nevertheless, he went on to consider compensation under the Native Title Act. This was because the Jango case was the first litigated compensation case. This was not part of the reasons for his decision and is not binding (it is ‘obiter’). The judge’s comments do provide some insight into the significant procedural hurdles claimants are likely to have to overcome to obtain compensation under the Native Title Act.25

In order to receive compensation under the Native Title Act, the claimants must establish that:26

- they held native title rights and interests just prior to the ‘compensation acts’ they claim extinguished their native title. They must prove their rights in the same way as when applying for a determination that native title exists. This was the biggest issue for the claimants in Jango. Their evidence of native title wasn’t accepted by the court as being sufficient to prove native title;

- those native title rights and interests had not been extinguished by acts that do not attract compensation prior to the acts that do attract compensation occurring;

- the compensation acts extinguished, or otherwise diminished, the native title rights; and

- the amount of compensation that should be awarded as a result of compensation acts.

A failure to establish any of these things will defeat a compensation claim. The issue of compensation I consider in a broader context in the next chapter.

Evidence

In the Jango case evidence was a major issue. In a native title case the onus is on the applicants to provide sufficient evidence to prove their case on the balance of probabilities. This evidentiary burden is particularly heavy in native title cases where meeting the requirements under the Native Title Act to establish native title requires evidence going back to sovereignty.

Recognising the serious hurdles of proving native title, Justice Sackville stated:27

Claimants in native title litigation suffer from a disadvantage that, in the absence of a written tradition, there are no indigenous documentary records that enable the Court to ascertain the laws and customs followed by Aboriginal people at sovereignty. While Aboriginal witnesses may be able to recount the content of laws and customs acknowledged and observed in the past, the collective memory of living people will not extend back for 170 or 180 years.

Compensation cases may entail particular evidentiary hurdles:28

What is clear from Jango is that the persons who are entitled to compensation are those that held native title at the date the compensation act was undertaken. In future proceedings, the former holders of native title will have to provide evidence about their connection to land at that date. This evidentiary onus may become a burden for claimants when compensation acts occurred many years before and potential Aboriginal witnesses may not still be alive to give evidence needed.

Section 82

As well as the heavy evidentiary burden on the applicants, how the court treats and admits evidence is an issue in nearly all native title proceedings. The admissibility of evidence in native title proceedings is governed by Section 82 of the Native Title Act. The Federal Court under that section is bound by the rules of evidence ‘except to the extent that the Court otherwise orders’. Under Section 82(1) of the Native Title Act the court has the power to dispense with the rules of evidence. It did not do so in the Jango case.

Expert evidence

In Jango the expert evidence submitted by the compensation claim group became an issue early in the case. Justice Sackville rejected expert evidence presented to him by the claimant group.

He ruled on more than 1,100 objections by the Commonwealth and Northern Territory Governments to the admission into evidence of substantial portions of the two anthropological reports presented by the group claiming compensation.29 The objections related to the adequacy of the reports as expert evidence under the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) (the Evidence Act).

The majority of the objections concerned the:

- lack of distinction between fact and expert opinion;

- failure to identify the source of factual information relied upon;30and

- failure to demonstrate that opinion was based on specialised knowledge.

Justice Sackville concluded that the two reports had been prepared with ‘scant regard’ to the requirements of the Evidence Act.31 He endorsed the following statement of Justice Lindgren in the Wongatha case:32

Lawyers should be involved in the writing of reports by experts: not, of course, in relation to the substance of the reports (in particular, in arriving at the opinions to be expressed); but in relation to their form, in order to ensure that the legal tests of admissibility are addressed. In the same vein, it is not the law that admissibility is attracted by nothing more than the writing of a report in accordance with the conventions of an expert’s particular field of scholarship. So long as the Court, in hearing and determining applications such as the present one, is bound by the rules of evidence, as the Parliament has stipulated in s82(1) of the [Native Title Act 1993 (Cth)], the requirements of s7933 (and s5634 as to relevance) of the [Evidence Act 1995 (Cth)] are determinative in relation to the admissibility of expert opinion evidence.35

Justice Sackville criticised the claimants’ Yulara Anthropology Report:36

[The report] does not clearly expose the reasoning leading to the opinions arrived at by the authors. Nor does it distinguish between the facts upon which opinions are presumably based and the opinions themselves. Indeed, it is often difficult to discern whether the authors are advancing factual propositions, assuming the existence of particular facts, or expressing their own opinions. Certainly the basis on which the authors have reached particular conclusions is often either unstated or unclear.

A strong case fails?

Uluru—most Australians would see this as the heart of Indigenous Australia. A sacred place, clearly part of the ‘Aboriginal domain’, Yulara sits in its shadows. Aboriginal people are the joint managers of Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park. The area is surrounded by land held by Aboriginal Land Trusts. Yet the Yankunytjatjara and Pitjantjatjara and other Indigenous people of Yulara failed to have their rights recognised. The Native Title Act and the way the common law has interpreted it failed to provide them with compensation for extinguishment of their native title.

It must be asked, as it often is by traditional owners around the country, how this can happen? As one witness in the Wongatha case summed it up when he said words to the effect, ‘if I cannot claim native title in this area, where can I claim it?’.36 As the judge in that case pointed out:37

the implication [of the question] is that a Judge will surely have no difficulty in seeing that the witness must have native title somewhere. The fact is, however, that since the establishment of British sovereignty...there has been a new sovereign legal system, the laws of which are determinative of legal questions.

The concern I have is that the law, both the Native Title Act and the interpretation given it by the common law, are not allowing for compensation for extinguishment or for the full recognition and protection of native title. The preamble states that ‘Justice requires that, if acts that extinguish native title are to be to validated or to be allowed, compensation on just terms and with a special right to negotiate its form, must be provided to the holders of the native title.’ This is not occurring.

The Jango case is an example of a case considered strong by many. The judge recognised the strength of the claim. Yet it failed due to the particular difficulties of producing evidence to support a claim in native title proceedings, and because of difficulties in how it was pleaded. The difficulties in pleading the case are themselves an indication of the complexity of the law and the difficulty in pursuing native title determinations.

Section 82 of the Evidence Act provides the ‘default’ position on evidence in native title proceedings. The rules of evidence apply, including the rules on hearsay and opinion evidence. The special characteristics of Indigenous evidence in native proceedings makes such evidence particularly vulnerable to technical and collateral attacks on a claimants’ case. This occurred in the Jango case. These can be extremely time consuming and diverting. The issue of evidence is considered in detail in the next chapter.

Technical attacks are part of the wider issue of native title proceedings taking place in an adversarial context. In such a context the respondent parties are entitled to take objection to every point of the claimant’s case. Their job, in the adversarial setting, is to attack the claimant’s case where ever possible.

Bennell v Western Australia

The Federal Court determined on 19 September 2006 that native title exists over Perth. Bennell v Western Australia (the Noongar case)38 was the first decision that native title existed over a capital city in Australia.39 Justice Wilcox handed down the decision. The Australian and Western Australian governments appealed to the Full Federal Court. The appeal was heard in April 2007. At the time of writing this report the appeal decision had not yet been handed down.

The case highlights:40

- the difficulties the court faces in applying the definition of native title in Section 223 of the Native Title Act 1993; and

- the procedural complexities that can arise during lengthy and resource intensive native title cases.

While Justice Wilcox held that a limited number of the native title rights asserted by the applicants have survived, the final determination and the precise wording of that determination are to be decided between the parties.

The case

Eighty applicants acting on behalf of the claimant group, the Noongar people, commenced action in the Federal Court in October 2005 to have their native title rights and interests determined. The land subject to the Single Noongar Claim was in the southwest corner of Western Australia and included Perth.41 The primary respondent to the application was the Western Australian Government. The Commonwealth Government also became a party to the proceeding. Sixty-six other respondents were listed as parties.

The judge determined that native title rights and interests exist over the land; that the Noongar people are the traditional people for the southwest corner of Western Australia. He accepted that Perth, in the middle of this region, has always been part of Noongar country.

Satisfying the requirements of native title

Section 223 of the Native Title Act defines native title. The three elements of that section must be established in any native title proceedings. The first of these is that the rights and interests claimed as native title must be possessed by the claimants under the traditional laws acknowledged, and the traditional customs observed, by Aboriginal peoples or Torres Strait Islanders. The laws and customs must be traditional.

Since the High Court’s decision in the Yorta Yorta case, for the laws and customs to be traditional there must be a ‘normative society’ that has continued to exist from the date of sovereignty until today.42 That society must have continued to observe law and custom from that date. The claimants must establish that the content of that law and custom has continued to the present day.43

Society

Justice Wilcox accepted the applicant’s case that a single Noongar society existed in 1829 and that it continues to the present day as a body united by its observance of traditional laws and customs.

The judge concluded that as a matter of law Yorta Yorta requires only that the applicants show a ‘common normative system’ at sovereignty. It was not required to show a subjective sense of community, or some ‘other factors which demonstrate unity and organisation’ beyond common observance of traditional law and custom.44

In Justice Wilcox’s words:45

The applicants’ case was that the Noongar people continued to exist as a society, although in a changed form, and to apply, as between themselves, the traditional landholding rules.

The evidence led him to conclude:46

that, in 1829, there was a single society that occupied the whole of the claim area and whose laws and customs regulated land rights.

…

The basis of my conclusion was compelling evidence about five matters: the continuing use of the Noongar language by many people throughout the claim area; the adherence by all the witnesses to a complex of spiritual beliefs that accorded broadly with the beliefs noted by the early European writers and were widespread in the claim area; the maintenance of traditional hunting practices, even where this was not necessary for food-gathering purposes; the continuing coming-together of people for festivals, funerals etc; and, most importantly, the continued adherence, by many people, to the traditional rule about seeking permission to visit someone else’s country.

Justice Wilcox found that in 1829 the claim area was occupied and used by ‘Aboriginal people who spoke dialects of a common language and who acknowledged and observed a common body of laws and customs’.47 He accepted that what united and distinguished them from neighbouring groups was a ‘commonality of belief, language, custom and material culture’.48 Though sub-groups or families exercised particular rights and responsibilities for particular areas to which they ‘belonged’, those rights and responsibilities arose from a wider normative system that operated within the broader Noongar society.49 The rights of the sub-group were burdened by the entitlement of others to access land for various purposes.50

Substantial continuity of traditional laws and customs

In Yorta Yorta51 the High Court made it clear that two factors in particular can interfere with continuity of a society and continuity in the observance of traditional law and custom:52

- too much adaptation or change to the content of law and custom; or

- substantial interruption to the observance of law and custom.

These two factors have become key issues to Federal Court judges applying the law:

- what is a degree of tolerable adaptation and change to the content of law and custom; and

- what degree of interruption to the observance of law and custom and to societal continuity is acceptable.

In the De Rose case53 the Full Federal Court said that continuity in the observance of law and custom is a question of fact and degree. It is likely the question in many cases will be whether the community or group as a whole has ‘sufficiently’ observed law and custom.

In the Noongar case, Justice Wilcox took himself back to the question:

whether the normative system revealed by the evidence is “the normative system of the society which came under a new sovereign order” in 1829, or “a normative system rooted in some other, different society”?

He found the current normative system of the Noongar people belongs to the Noongar society that existed at sovereignty and continues to be united by its observance of some of its traditional laws and customs. He conceded the enormous impact of European settlement and the cessation of observance for many traditional laws and customs. Nevertheless, conspicuously observing the verbal limitations set down by the High Court in Yorta Yorta,54 he said that Noongar normative system was:55

much affected by European settlement; but it is not a normative system of a new, different society.

The modifications to traditional law observed by Justice Wilcox, were, in his view, within the parameters of acceptable change and adaptation; the story of the Noongar was held to be one of continuity and adaptation.56

In examining the issue of continuity, the judge looked at different aspects of the society. He found:57

- consistent evidence of spiritual beliefs, across age groups and across widely scattered parts of the claim area;

- reasonably strict and consistent marriage rules;

- less cogent evidence as to burial practices; and

- strong signs that ‘lawful’ conduct in relation to hunting, fishing and food-gathering remained important and was taught to younger family members.

With regard to descent and claims to land, he found that at the date of sovereignty there was a general rule of patrilineal descent (claiming through your father’s side) with some exceptions. Today the exceptions have widened, so that claims based on matrilineal descent (claiming through your mother’s side) are common. Now, there is a greater element of individual choice in deciding which of those two ways people go in claiming rights in land.

Justice Wilcox said that widening the exceptions to the general rule regarding descent was a realistic response to the widespread fathering of Aboriginal children by non-Aboriginal men. Changing descent rules was necessary to sustain the general operation of land rules across Noongar society. Likewise, other impacts, like dispossession and child removal, had made it ‘obviously necessary’ to allow a degree of choice of descent for country greater than ‘what would have been necessary in more ordered, pre-settlement times’.58

Concerning the traditional rule of seeking permission to visit a sub-group’s country, Justice Wilcox found:59

- striking similarities with the accounts of earlier writers, allowing for what he regarded as an acceptable level of adaptation to changed circumstances;

- the rule had adapted to modern circumstances – so that it would not apply ‘if merely driving through another’s country on the way to somewhere else’ or ‘visiting Perth on business or for medical treatment’; and

- ‘the rule is regarded as extant and its breach strongly disapproved’.

The future of the Noongar case

At the time of writing the Full Federal Court had not handed down its decision on the appeal in the Noongar case. If the court upholds the decision there are still many hurdles to overcome before the Noongar people can practically access their native title rights and interests. Justice Wilcox has retired. A new judge will need to hear any outstanding issues. These include determining:

- the precise nature of the native title rights and interests. (Justice Wilcox heard and determined only some of the issues involved in the Part A matter (primarily whether traditional connection was established and maintained by the Noongar and what rights could be demonstrated to exist today).)

- the remaining Single Noongar Claim area (the area was split into Part A (Perth Metropolitan Area) and Part B (the remaining part of the claim area)). Part B remains to be determined.

- which native title rights and interests have been extinguished.

- whether the Noongar people are entitled to compensation under the Native Title Act.

A right to compensation may arise if there was an extinguishment of native title rights and interests between the Racial Discrimination Act 1975 coming into force (on 30 October 1975, thereby making it discriminatory to extinguish the native title rights) and the commencement of the Native Title Act on 1 January 1994.60

Many of the acts which extinguished the Noongar people’s rights will go uncompensated. However, almost half of Perth’s current population has been accommodated since the Racial Discrimination Act came into effect.61 This may mean a high proportion of extinguishing acts in the Perth metropolitan area are acts that must be compensated.

The broader issue of compensation for extinguishment of native title is considered in the next chapter.

Risk v Northern Territory

Risk v Northern Territory and Quall v Northern Territory (the Larrakia case)62 was a decision of the Federal Court given by Justice Mansfield on 29 August 2006. The court determined that native title rights and interests do not exist over an area that includes Darwin. The case was the second litigated native title determination over a capital city. Important aspects of the case are:

- issues of evidence; and

- the level of ‘continuity’ required by the definition of native title in Section 223 of the Native Title Act.63

An appeal to the Full Federal Court was dismissed.64 The Larrakia were refused special leave to appeal to the High Court on 31 August 2007. There is no further avenue of appeal.

Overall, what the Larrakia case makes clear is how fragile the legal concept of native title is, when compared with notions of culture and identity. The break in continuity of traditional laws and customs that was sufficient for the court to find native title did not exist was a few decades (post World War II). The Larrakia revitalised their culture, laws and customs after this break. It was not enough.

I am deeply concerned that the passage of a few decades (even where unavoidable, significant impacts are experienced), is enough to see native title, as recognised by Australian law, gone forever. And this, where the culture under consideration has existed for over 40,000 years.

The case

William Risk and others, representing the native title claim group of the Larrakia people,65 applied to the Federal Court to have a native title determination made over an area covering parts of Darwin and its surrounds. The area comprised about 30 square kilometres of land and water most of which was Crown land or held by Darwin City Council and Palmerston City Council.66 The area generally has not been used for commercial or residential development. The case considered Part A of consolidated proceedings. Part B has not yet been determined.67

The claim was contested by the Northern Territory Government, Darwin City Council and the Amateur Fisherman’s Association of the Northern Territory. There were 15 other respondents to the claim.

Justice Mansfield determined that no native title rights and interests were held by the Larrakia people over the land. This was because the current laws and customs were not ‘traditional’ as required under Section 223(1)(a) of the Native Title Act:68

…the evidence demonstrates an interruption to the Larrakia people’s connection to their country and in their acknowledgement and observance of their traditional laws and customs so that the laws and customs they now respect and practice are not ‘traditional’ as required by s223(1) of the NT Act.

Just as Justice Wilcox in Noongar, Justice Mansfield noted that the requirement for continuity in Yorta Yorta69 is not absolute but acknowledgement and observance of traditional laws and customs must have continued ‘substantially uninterrupted’ since sovereignty.

I have found that, at sovereignty, there was a society of indigenous persons who had rights and interests possessed under traditional laws and customs, and giving them a connection to the land and waters of the claim area. I have also found that that society continued to exist to European settlement from about 1869, and continued to exist into the 20th century, and that it continued to enjoy rights and interests under the same or substantially similar traditional laws and customs as those which existed at sovereignty. I have also found that the society was the Larrakia people, and not some different indigenous group. …

The evidence shows that a combination of circumstances has, in various ways, interrupted or disturbed the presence of the Larrakia people in the Darwin area during several decades of the 20th century in a way that has affected their continued observance of, and enjoyment of, the traditional laws and customs of the Larrakia people that existed at sovereignty. The settlement of Darwin from 1869, the influx of other Aboriginal groups into the claim area, the attempted assimilation of Aboriginal people into the European community and the consequences of the implementation of those attempts and other government policies (however one might judge their correctness), led to the reduction of the Larrakia population, the dispersal of many Larrakia people from the claim area, and to a significant breakdown in Larrakia people’s observance and acknowledgement of traditional laws and customs. …

I have concluded that during much of the 20th century, the evidence does not show the passing on of knowledge of the traditional laws and customs from generation to generation in accordance with those laws and customs.70

Risk and others appealed to the Full Federal Court. The appeal was unsuccessful, and leave to appeal to the High Court was refused.

A native title determination has effect in rem – it is binding on the whole world.71 Therefore, the court’s finding is conclusive that native title does not exist in the area covered by the applications, whether by the Larrakia people or anyone else.

Satisfying the requirements of native title

As in all native title proceedings, the Larrakia people, to gain recognition of their native title, needed to meet the definition of native title set out in Section 223 of the Native Title Act. A key aspect of this definition is the need to show substantial continuity of traditional laws and customs.

Substantial continuity of traditional laws and customs

The Larrakia’s case is the first conclusive application of Yorta Yorta principles applying ‘interruption’ of the continuity of observance of traditional laws and customs to the dismissal of a native title application.

The key issue for Justice Mansfield in evaluating the Larrakia application was whether the claimants could demonstrate that their contemporary laws and customs were ‘traditional’. This is in the sense of:

- being handed down from the pre-sovereign society (that they had their ‘origin in’); and

- a continued observance of traditional law and custom since sovereignty.

Justice Mansfield noted that some interruption in observance or change or adaptation of traditional law and custom ‘will not necessarily be fatal to a native title claim’.72 However observance must be substantially uninterrupted. Justice Mansfield concluded that, on the evidence, the Larrakia claim group had failed the ‘substantially uninterrupted observance’ test.

The time during and after World War II (WWII) was crucial to his conclusion. The judge considered there was only limited observance of the law and custom at the outset of WWII. This combined with further erosion of the practice of law and custom during and after WWII amounted to substantial interruption. The erosion was facilitated by removal of most Aboriginal people (and others) from Darwin during the war. It was exacerbated by policies of Aboriginal assimilation that the government applied after their return.

The evidence over this period did not, in Justice Mansfield’s view, point to continued observance of most of the Larrakia traditional laws and customs.73 Later evidence of cultural revitalisation was not sufficient to overcome the break in continuity of observance.74

Justice Mansfield made it clear that observance of law and custom will be measured holistically. In reaching his conclusion he examined many aspects of the society, including:

- cultural organisation and practices;75

- economy and resource use;76

- spirituality;77

- social structure;78

- language;79 and

- country including, the extent of Larrakia country, feeling good about country, and looking after sites.80

The judgment demonstrates the breadth of inquiry that may be undertaken by the court in order to determine continual observance of traditional laws and customs.

Risk and others appealed to the Full Federal Court on three grounds.81 One of the grounds they argued was that Justice Mansfield had incorrectly applied Yorta Yorta82 in finding that the traditional laws and customs of the Larrakia people had been discontinued. The full court rejected this argument. It was satisfied Justice Mansfield had considered the evidence of law and custom between the time of sovereignty and the present.83 The court was also satisfied that Justice Mansfield did not consider physical absence from places in the Larrakia claim as criteria for determining interruption.84 The Full Federal Court observed:85

It is not that the dispossession and failure to exercise rights has, ipso facto, caused the appellants to have lost their traditional native title, but rather that these things have led to the interruption in their possession of traditional rights and observance of traditional customs.

In discussing the issue, the court noted that neither Yorta Yorta86 nor Western Australia v Ward87 suggest that using the land and waters or exercising rights over them are crucial to proving continuity.

In his judgment, Justice Mansfield referred to the transmission of knowledge of traditional law and custom by traditional means. The appellants considered that this imposed an additional requirement that knowledge be obtained in a certain way. The Full Federal Court disagreed:88

…No doubt the failure of a claimant group to continue to pass on knowledge of other customs and laws by word of mouth will not necessarily be fatal to their claim. But it may be evidence of an interruption in customs and laws generally. It is a factor that the trial judge rightly took into account in coming to his conclusion.

In summary, the Full Federal Court found that:

[Justice Mansfield’s] findings that Larrakia did not maintain the acknowledgement of their traditional laws and observance of their traditional customs are based upon evidence, particularly from older members of the Larrakia group, that practices they had engaged in during the first half of the twentieth century did not last into the second half. The submission that his Honour inferred interruption from change is not supported by a close reading of his reasons. No inferences needed to be drawn, it was apparent to his Honour on the evidence that there had been a substantial interruption.89

The Noongar case and the Larrakia case

The requirement that there be a ‘society’ and that there be a continuity of that society is not written into the Native Title Act. It is a requirement arising from the common law (the High Court’s decision in Yorta Yorta). Since that case there has been much concern amongst participants in the native title system about how this requirement would be interpreted and applied by courts in native title proceedings.

The Noongar case and the Larrakia case highlight divergent applications of the requirement. Both cases involved metropolitan areas. In the Noongar case the court found the requisite society and continuity of that society. In the Larrakia case, the court didn’t. Each case is decided on its own particular facts. Nevertheless, I am concerned that the requirements of society and continuity are open to an interpretation that is unjustly harsh on Indigenous peoples and their ability to gain recognition of their native title. I am concerned that the requirements are out of step with the reality of contemporary ideas of how societies evolve. That it is too narrow and constraining. And, most particularly, that it fails to recognise that government policies like forced removal and assimilation contributed to a break in continuity. Nor does it give a place to the resurgence and revitalisation of culture and tradition. The latter is an important aspect to the human rights of Indigenous peoples.

I take these issues up in greater detail in the next chapter.

Evidence

Evidence presented to the court posed a problem. Two out of the three grounds for appeal centred on issues of evidence. Justice Mansfield commented on some of the difficulties associated with evidence in native title proceedings, particularly expert anthropological evidence.

Expert anthropological evidence

Observations by Justice Mansfield about expert anthropological evidence have been succinctly summarised by the National Native Title Tribunal.90 The judge noted:

- it is important that the intellectual processes of the expert can be readily exposed;

- that involves identifying, in a transparent way, what are the primary facts assumed or understood;

- it also involves making the process of reasoning transparent and, where there are premises upon which the reasoning depends, identifying them;

- the premises, whether based on primary facts or on other material, then need to be established;

- at least in the context of expert anthropological reports, the line between an opinion and the fact upon which that opinion is based is not always clear;

- while the clear separation of fact and premise from opinion is clearly desirable, it is necessary to accept that there is sometimes difficulty in discerning between the facts upon which an opinion is based and the opinion itself in an expert anthropology report; and

- such a difficulty should not be regarded as a fatal flaw that may render the report or the opinion inadmissible.

Oral evidence

The Larrakia people appealed on the ground that Justice Mansfield had failed to take into account critical evidence. It was contended that Justice Mansfield had failed to consider and evaluate a large body of oral evidence from Aboriginal witnesses. This evidence went to whether there was a substantial interruption in the observance of traditional laws and customs in the middle decades of the 20th Century. The appellants argued the judge had confined his consideration of oral Aboriginal evidence to the contemporary Larrakia society of the last decade.

The Full Federal Court dismissed this claim. It held that ‘they were in no doubt that the trial judge was conversant with the evidence as a whole’.91 It was noted:

the primary judge had before him a complex case. There were 47 Aboriginal witnesses, many expert witnesses, and a great deal of documentary material. The hearing lasted 68 days… considerable caution is appropriate before the Full Court infers that crucial evidence was not evaluated and necessary findings of fact were not made.92

Failure to adopt the Kenbi Land Claim report

A ground of appeal was that Justice Mansfield did not adopt the Aboriginal Land Commissioner Justice Grey’s finding in the Kenbi Land Claim Report.93 Justice Grey’s finding was that under Aboriginal tradition, the Larrakia have attachments to and rights to forage over, occupy and use country associated with them.

Justice Mansfield stated:94

In the current proceedings, I am inclined not to adopt any of the findings of the Land Rights Commissioner in the Kenbi Report. The Kenbi Claim covered a claim area distinct from that involved in these proceedings. Not all of the witnesses who gave evidence before his Honour were called in these proceedings, for various reasons. The expert evidence was in part from different witnesses. The expert evidence too related to the different issues which arose under the [Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 (Cth)], and was in respect of different land. The matters to which those findings relate have also been, to varying degrees, the subject of additional and in some instances different evidence in the current proceedings. Those considerations have led me to the view which I have expressed.

The Larrakia people appealed this ground on the basis that it was a miscarriage of the exercise of discretion conferred on the judge by Section 86 of the Native Title Act. That section allows the judge to adopt evidence or findings from other proceedings. The full court rejected this ground for appeal holding that Justice Mansfield’s decision was appropriate and relevant.95

The judgment demonstrated the distinct nature of:

- native title proceedings; and

- inquiries undertaken by Aboriginal Land Commissioners under the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 (Cth).

Both entail an aspect of tradition. The Aboriginal Land Commissioner determines and reports on whether claimants making a ‘traditional land claim’, or any other Aboriginal persons, ‘are the traditional Aboriginal owners of the land’.96 The terms ‘traditional Aboriginal owner’ and ‘traditional land claim’ are defined as follows:97

traditional Aboriginal owners, in relation to land, means a local descent group of Aboriginals who: (a) have common spiritual affiliations to a site on the land, being affiliations that place the group under a primary spiritual responsibility for that site and for the land; and (b) are entitled by Aboriginal tradition to forage as of right over that land.

traditional land claim, in relation to land, means a claim by or on behalf of the traditional Aboriginal owners of the land arising out of their traditional ownership.

Despite dealing with similar subject matter both proceedings are distinct. The Larrakia case highlights that the courts will not automatically accept the finding of an Aboriginal Land Commissioner in a native title proceeding. This is even where the Indigenous peoples making the different claims under the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act and the Native Title Act are connected.

Harrington-Smith on behalf of the Wongatha People v Western Australia

Approximately 160,000 square kilometres of the Goldfields area of Western Australia, near the town of Kalgoorlie, were subject to a native title claim by the Wongatha people in Harrington-Smith on behalf of the Wongatha People v Western Australia (the Wongatha case).98 Justice Lindgren of the Federal Court dismissed the application on 5 February 2007 without making a determination whether native title rights and interests exist.

In response to the decision of the court dismissing the proceedings, the Commonwealth made a non-claimant application for native title to be determined over the area. This was discontinued.99

This discontinuation of the non-claimant application ‘largely finalises the most expensive native title litigation to date – without an approved determination of native title’.100

The case

The Wongatha case was ‘…arguably one of the most complex native title cases yet heard by the Federal Court’.101 The primary reasons for the complexity included:

- the way the claim groups were constituted;

- the complexity of Western Desert society and its landholding arrangements; and

- the number of parties involved in the litigation.102

In August 1994 a native title claim was lodged with the National Native Title Tribunal (the tribunal) on behalf of the Wajlen people. On 18 December 1998, at a meeting of ‘certain members of certain antecedent claim groups’,103 a resolution was made to add a number of further parties to the claim. In January 1999, an application was sought to amend the claim to reflect that resolution. Later that month, a Deputy District Registrar of the Federal Court ordered that the native title claim be combined with 19 other proceedings to form the Wongatha claim.104 The result was that the Wongatha claim group comprised 820 individuals in 2002, and was a combination of 20 claims.105

When the claim came before the Federal Court for a determination, the court was not just determining the consolidated Wongatha claim. There were an additional seven overlapping claims to be considered. The court heard these claims to the extent that they overlapped with the Wongatha claim area.

This history helped produce a complex case that consumed considerable resources of people, time, money, emotion and energy:106

The judgment itself runs over 1,000 pages, not including annexures. The court sat for 100 hearing days in various locations…the transcript of which amounted to almost 17,000 pages. There were a total of 149 witnesses…volumes of expert reports (34) and volumes of submissions (97), not including extinguishment.

It was the first time a court had dealt with so many native title claims in the one proceeding.

The finding

Justice Lindgren found that seven of the eight claims (including the Wongatha peoples’ application) were not authorised as required by Sections 61(1) and 61(4) of the Native Title Act.107 Therefore, he held that the court didn’t have the jurisdiction to hear the applications and he dismissed the claims.108 He made no determination on the existence or absence of native title.

The current requirements for authorisation were inserted in the Native Title Act by the 1998 amendments (which followed the Wik decision). In the Wongatha case the applications were made prior to the 1998 amendments. The applications were then amended after 1998. Justice Lindgren held that the amendments to the applications triggered the new, more stringent, post-1998 authorisation requirements. These had not been adhered to.109

Despite this finding, Justice Lindgren went on to consider the claims.110 He found that there existed a Western Desert Cultural Bloc (WDCB) society at the time of sovereignty (in Western Australia this is taken to be 1829). This society continues to exist today.111 However, he questioned whether the WDCB was a ‘society’ with laws and customs that would give rise to native title rights and interests in relation to land and waters.112

The notion of a single overarching society with regional societies within it seems useful. Accordingly, although with some doubt, I proceed on the basis that the WDCB is a ‘society’ in the sense described in Yorta Yorta HCA …113

Accordingly, I find that there was in 1829 a WDCB society that had a body of laws and customs that provided for multiple pathways of connection, through which an individual might hold rights and interests, and that the Wongatha Claim area, but no further west than the Menzies-Lake Darlot line, was subject to that body of laws and customs. This says nothing, however, as to the subject matter of the rights and interests, that is, the identification of the land the subject of them...114

The claim failed because:115

1. The Wongatha applicants were not authorised to make the Wongatha application as required by s 61(1) of the NTA [Native Title Act].

2. The evidence does not establish that the Wongatha Claim group is a group recognised by WDCB traditional laws and customs as a group capable of possessing group rights and interests in land or waters.

3. The evidence does not establish that group rights and interests exist in the Wongatha Claim area under WDCB traditional laws and customs.

4. The evidence does not establish that at sovereignty, WDCB laws and customs provided for an ancestral group of the Wongatha Claim group to possess group rights and interests in the Wongatha Claim area, or for individuals to be able to form themselves into a group possessing such rights and interests.

5. The Wongatha Claim is an aggregation of claims of individual rights and interests, and the Wongatha Claim area is based on an aggregation of individual ‘my country’ areas, the subject of those claimed individual rights and interests, and the NTA does not provide for the making of a determination of native title consisting of group rights and interests in these circumstances.

6. The Wongatha Claim area is not an area that is ultimately, whether directly or indirectly, defined by reference to Tjukurr (Dreaming) sites or tracks.

7. Approximately the western one sixth of the Wongatha Claim area lies outside the area of the WDCB ‘society’ on which the Wongatha Claim is based.

8. Many, if not most or all, of the Wongatha claimants are the descendants of people who migrated into the Wongatha Claim area from desert areas outside that area, in particular, to the east of it, since, and under the influence of, European settlement, and it is not established that their ancestors had any connection with the Wongatha Claim area at sovereignty, or that they or the Wongatha claimants descended from them, acquired rights and interests in the Wongatha Claim area in accordance with pre-sovereignty WDCB laws and customs.

9. The evidence does not establish that the claimants constituting the Wongatha Claim group have a connection with the Wongatha Claim area by Western Desert traditional laws and customs as required by s 223(1)(b) of the NTA.

Ultimately Justice Lindgren declined to make a finding that there was no native title as he considered that the claim group did not have the required authority to apply for a determination:116

There is some acknowledgement and observance of some traditional laws and customs by some Wongatha claimants. Does the evidence lead to the conclusion that there is acknowledgement and observance by the Wongatha Claim group of the pre-sovereignty Western Desert laws and customs? As I indicated…I am refraining from answering this question.

However he did consider that he had set out the primary facts in sufficient detail for the Full Federal Court on the appeal to make a finding on continuity of observance and make a determination if they so decided.117

The Wongatha case – a system failure?

The Wongatha case was dismissed because Justice Lindgren found that the applicants did not have the authority required under Section 61 of the Native Title Act.

I am concerned at what appears to have been a major failure of the native title system in the Wongatha case. The case ultimately failed because the applicants were not authorised to make the application as required by the Native Title Act. It is unclear why the failure to overcome the technical requirement of authorisation was not identified early in the history of the claim. Over the 12 years of complex litigation no party involved in the running of the proceeding appears to have identified this problem. The system appears to have failed to identify it until into the hearing, and this has failed the Aboriginal claimants.

At the time the case was heard, the Native Title Act was unclear about whether the court had the power to continue to hear and determine native title when the application was not properly authorised.118 Yet, as was evidenced in Wongatha, ‘ [q]uestions about the validity of the applicant’s authorisation can arise at any stage during proceedings’.119

To deal with this problem, the Native Title Act was amended a few months after the Wongatha decision, to include Section 84D.120 This section provides:

- applicants may be required to provide greater evidence that they have been authorised to make a claim on behalf of the claim group; and

- where an applicant has not satisfied the Section 61 authorisation requirements, the court may still determine native title (or make any other order it considers appropriate) if it decides it is appropriate ‘after balancing the need for due prosecution of the application and the interests of justice’.121

I am concerned that in making these amendments the government has not given full consideration to the objectives of the Native Title Act and to ensuring that all Indigenous people have access to their native title rights and interests. I recognise the difficulty of the authorisation procedures set out in the legislation and the devastating impact’s failure to authorise can have on a case such as Wongatha. However, authorisation is essential to the native title system. It is unclear why the reference point for the court’s decision to disregard the authorisation requirements (as allowed by the new section 84D) is ‘the need for due prosecution of the application and the interests of justice’.

The authorisation provisions in the Native Title Act are a safeguard to ensure that consultation occurs. They are there to ensure that the free, prior and informed consent of the Indigenous people whose rights and interests are being affected is obtained. It is essential that the right people are the applicants on any native title claim. This is an ongoing consideration throughout the whole process of claiming native title. While recognising that the authorisation provisions are causing many difficulties, this primary objective should be the key consideration of the court when deciding whether they should continue to hear the claim in the absence of satisfying Section 61.

The outcome of the case raises concerns about the resources exhausted by the case and the practical implications to the Wongatha people of their case being dismissed. The case is the most expensive native title litigation of native title to date.

One would have hoped that after such a lengthy and expensive hearing there would have been some certainty for the parties. Instead, this judgment adds yet another layer of uncertainty to native title case law…the main lesson that can be drawn from the Wongatha case is that the use of the court to adjudicate relationships between indigenous and non-indigenous Australia is a recipe for disaster.122

The Wongatha case was contested rigorously in the court system. It has been suggested one reason for this was because the Wongatha’s claim was over a resource rich part of the State and land which is ‘economically extremely valuable to the WA State government’.123

Justice Lindgren referred to the seemingly unfair contest of some claims over others. Justice Lindgren recognised this in his summary accompanying his judgment:

some native title cases are strongly contested, while others are not. In pre-contact times, the indigenous people in two areas would have used the surface for camping, hunting, foraging and so on. Yet, in one case there is a consent determination and in the other there is a contest to the bitter end. Why? The reason relates to the value placed on the land by others. This is readily understandable, but has nothing to do with the respective merits of the two cases.124

The future of the Wongatha claim

Justice Lindgren specifically stated in his judgment that he wasn’t intending to preclude or encourage the groups to apply for a determination in the future.125 The result of the dismissal of the case means that differently constituted claim groups can make new claims over the claim area. The native title representative body for the claimants says that the group plans on pursuing new claims that are well considered and which have the maximum opportunity to achieve consent determinations. The State of Western Australia has agreed to consider new claims pursuant to its connection guidelines. It has indicated its preference to avoid further litigation.126 Mediation between the parties previously failed in this case.127

Footnotes

[1] Jango v Northern Territory (2006) 152 FCR 150 and Jango v Northern Territory (2007) 159 FCR 531.

[2] Bennell v Western Australia (2006) 230 ALR 603.

[3] Risk v Northern Territory and Quall v Northern Territory [2006] FCA 404 and Risk v Northern Territory and Quall v Northern Territory (2007) 240 ALR 75.

[4] Harrington-Smith on behalf of the Wongatha People v Western Australia (No 9) (2007) 238 ALR 1.

[5] It should be noted that not all of these four cases have exhausted the judicial process. The status of each case is given throughout this chapter.

[6] However, this number does not include other Federal Court cases on native title that were heard throughout the year which did not result in a native title determination. The National Native Title Tribunal Annual Report sets out these determinations and other Federal Court cases on native title that were heard through out the year. See the National Native Title Tribunal, Annual Report 2006-07, Commonwealth of Australia, 2007, available online at http://www.nntt.gov.au/publications/annual_report_06-07.html.

[7] National Native Title Tribunal, Annual Report 2006-07, Commonwealth of Australia, 2007, available online at http://www.nntt.gov.au/publications/annual_report_06-07.html, p18.

[8] Jango v Northern Territory (2006) 152 FCR 150.

[9] Jango v Northern Territory (2007) 159 FCR 531.

[10] At the writing of this report, the Full Federal Court had reserved its decision on who would pay the costs of the litigation. Once costs are determined, the parties may choose to seek leave to appeal to the High Court.

[11] If you would like more detail on the case itself and a legal analysis of the decisions of the court, see Jowett, K. and Williams K., ‘Jango: Payment of Compensation for the Extinguishment of Native Title’, Land, Rights, Laws: Issues of Native Title (May 2007), Volume 3 (Paper No.8), Native Title Research Unit, Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, and National Native Title Tribunal, ‘Compensation application over Yulara – Jango case’, Issue 19, Native Title Hot Spots, available online at www.nntt.gov.au/newletter/hotspots/. See also Webb, R. and Kennedy G., ‘Case note: the application of Yorta Yorta to native title claims in the Northern Territory – the city and the outback’, (2006), 25 Australian Resources and Energy Law Journal, p201.

[12] The claim was for compensation from the Northern Territory because the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) deems the State or Territory responsible for extinguishment by ‘past acts’: s 20(3). The Commonwealth’s strong interest in the case presumably stems from the understanding that it would meet 75% of the compensation liability shouldered by States and Territories. See Jango v Northern Territory [2006] FCA 318, per Sackville J, para [12]. There was a third respondent – GPT Management Ltd, the holder of leasehold and freehold interests in the area covered by the compensation application, However GPT Management Ltd did not take an active part in the trial and did not enter an appearance for the appeal. See Jango v Northern Territory [2006] FCA 318, per Sackville J, para [13].

[13] No native title determination had been made in relation to any part of the relevant area and there was no dispute that all native title rights and interests that otherwise might have existed had been extinguished. See Jango v Northern Territory [2006] FCA 318, per Sackville J, para [6].

[14] Jango v Northern Territory [2006] FCA 318, per Sackville J, para [440]-[451].

[15] Minter Ellison, Native Title Act Unclear on Approach to Compensation, April 2006, available online at www.hg.org, accessed August 2007.

[16] This same grouping was relied on for the Wongatha claim (see below) and other significant native title cases such as De Rose v South Australia No 2 (2005) 145 FCR 290.

[17] Jango v Northern Territory (2006) 152 FCR 150, per Sackville J, para [8].

[18] Brennan, S., Recent Developments in Native Title Case Law, Presentation at the Human Rights Law Bulletin Seminar: Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission, Sydney, 4 June 2007.

[19] Jango v Northern Territory (2006) 152 FCR 150, per Sackville J, para [446] – [448], [452].

[20] Jango v Northern Territory (2006) 152 FCR 150, per Sackville J, para [497] – [507].

[21] Jango v Northern Territory (2006) 152 FCR 150, per Sackville J, para [40].

[22] Jango v Northern Territory (No 6) [2006] FCA 465 (3 May 2006).

[23] Although the applicants’ notice of appeal contained 12 grounds of appeal, set out at Jango v Northern Territory (2006) 152 FCR 150, per Sackville J, para [62], these were dealt with as the two grounds described: see Jango v Northern Territory (2007) 159 FCR 531, para [65].

[24] Jango v Northern Territory (2007) 159 FCR 531, para [84].

[25] Minter Ellison, Native Title Act Unclear on Approach to Compensation, April 2006, available online at www.hg.org, accessed August 2007.

[26] Minter Ellison, Native Title Act Unclear on Approach to Compensation, April 2006, available online at www.hg.org, accessed August 2007.

[27] Jango v Northern Territory (2006) 152 FCR 150, per Sackville J, para [462].

[28] Jowett, K. and Williams K., ‘Jango: Payment of Compensation for the Extinguishment of Native Title’, Land, Rights, Laws: Issues of Native Title (May 2007), Volume 3 (Paper No.8), Native Title Research Unit, Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, p11.

[29] Jango v Northern Territory (2006) 152 FCR 150, per Sackville J, para [313].

[30] Justice Sackville noted, at Jango v Northern Territory (No 2) [2004] FCA 1004, para [33], that Federal Court authority supports the view that Section 79 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) does not impose the ‘basis rule’ that exists at common law – the ‘requirement that for an expert’s opinion to be admissible, it must be based on facts stated by the expert and either proved by the expert or assumed by him or her and proved [from another source]’. However, Justice Sackville then proceeds to effectively impose the rule in his summary of the treatment of Commonwealth and Territory objections. He does so under the guise of the Section 79 Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) requirement for an expert report to demonstrate how it is based on specialised knowledge.

[31] Jango v Northern Territory (No 2) [2004] FCA 1004, per Sackville J, para [8].

[32] Jango v Northern Territory (No 2) [2004] FCA 1004, per Sackville J, para [11].

[33] Section 79 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) states ‘Exception: opinions based on specialised knowledge - If a person has specialised knowledge based on the person’s training, study or experience, the opinion rule does not apply to evidence of an opinion of that person that is wholly or substantially based on that knowledge’.

[34] Section 56 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) states: ‘Relevant evidence to be admissible - (1) Except as otherwise provided by this Act, evidence that is relevant in a proceeding is admissible in the proceeding. (2) Evidence that is not relevant in the proceeding is not admissible’.

[35] Harrington-Smith v Western Australia (No 7) [2003] FCA 893 per Lindgren J, para [19].

[36] Jango v Northern Territory (No 2) [2004] FCA 1004, per Sackville J, para [11].

[37] Harrington-Smith on behalf of the Wongatha People v State of Western Australia (No 9) (2007) 238 ALR 1, per Lindgren J, summary, p2.

[38] Harrington-Smith on behalf of the Wongatha People v State of Western Australia (No 9) (2007) 238 ALR 1, per Lindgren J, summary, p2.

[39] Bennell v Western Australia (2006) 230 ALR 603.

[40] Native title had at this point been recognised in urbanised areas such as Broome (see Rubibi Community v Western Australia (2001) 112 FCR 409) and Alice Springs (see Hayes v Northern Territory (1999) 97 FCR 32).

[41] If you would like more detail on the case itself and a legal analysis of the decisions of the court, see National Native Title Tribunal, ‘Proposed Determination of Native Title – Single Noongar application’, Issue 21, Native Title Hot Spots, available online at http://www.nntt.gov.au/newsletter/hotspots/1160012986_1792.html, Jowett, K., ‘Native Title over Perth’, (December 2006), Vol 7, Issue 11, Native Title News, p196.

[42] The claim area included the whole of Perth and centres of Bunbury, Busselton, Margaret River, Albany, York, Toodyay, Katanning, Merredin and other towns. The Federal Court only considered native title rights within the Perth Metropolitan Area (PMA), a sub-region that was split off by Justice Wilcox from the original single Noongar claim as ‘Part A’. The remainder of the claim area (‘Part B’) will be considered in a separate proceeding.

[43] Although the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) does not refer to the word ‘society’, the High Court held in Members of the Yorta Yorta Aboriginal Community v Victoria (2002) 214 CLR 422 that in order to satisfy the s.223 references to traditional laws and customs, claimants must be members of a society which is united in and by its acknowledgement of those laws and customs. Therefore claimants must show that they are members of a society that existed at sovereignty and continues to exist until today in order to satisfy s223 of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth). If that society has ceased to exist or ceased at some point, then the laws and customs of a group will not be considered traditional. See Members of the Yorta Yorta Aboriginal Community v Victoria (2002) 214 CLR 422.

[44] The date of ‘sovereignty’ varies across Australia. In Western Australia and the Northern Territory this date is taken to be 1829, for the Eastern Australian states, it is taken to be 1788 and for the Torres Strait it is taken to be 1879.

[45] ‘In Yorta Yorta, Gleeson CJ, Gummow and Hayne JJ seem to have regarded common acknowledgement and observance of a body of laws and customs as a sufficient unifying factor. Certainly, as is graphically illustrated by De Rose, it is not necessary that the ‘society’ constitute a community, in the sense of all its members knowing each other and living together. If that element was required, it would constitute an additional hurdle, for native title applicants, which would be almost impossible for most of them to surmount. The task of showing the existence of a common normative system some 200 years ago is difficult enough; it would be even harder to show the extent of the mutual knowledge and acknowledgment of those who then lived under that normative system, bearing in mind the non-existence of Aboriginal writings at that time’: Bennell v Western Australia [2006] FCA 1243, per Wilcox J, para [437].

[46] Wilcox, M., ‘The Noongar Native Title Claim’, in Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission, Us Taken-Away Kids, Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission, Sydney, 2007, p23.

[47] Wilcox , M., ‘The Noongar Native Title Claim’, in Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission, Us Taken-Away Kids, Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission, Sydney, 2007, p24.

[48] Justice Wilcox quoted these words from the applicants’ final written submissions. Bennell v Western Australia (2006) 230 ALR 603 per Wilcox J, para [84].

[49] Bennell v Western Australia [2006] FCA 1243, per Wilcox J, para [84].

[50] Although sub-groups enjoyed strong rights in relation to particular country, the picture was complicated by protocols for accessing neighbouring sub-group land and the different ways in which rights might be acquired. As the anthropologist called by the applicants Dr Palmer put it, ‘rights in land were not hermetically or exclusively bounded and more than one country group had rights to use country beyond their own. The exercise of such joint or shared rights was tempered by a requirement to follow protocols requiring the seeking of permission, for some activities, although this was not an invariable rule.’: Bennell v Western Australia (2006) 230 ALR 603, per Wilcox J, para [188]. See also para [297].

[51] Bennell v Western Australia (2006) 230 ALR 603, per Wilcox J, para [283], [297], [325].

[52] Members of the Yorta Yorta Aboriginal Community v Victoria (2002) 214 CLR 422.

[53] Members of the Yorta Yorta Aboriginal Community v Victoria (2002) 214 CLR 422.

[54] De Rose v South Australia No 2 (2005) 145 FCR 290, 305.

[55] Members of the Yorta Yorta Aboriginal Community v Victoria (2002) 214 CLR 422.

[56] Bennell v Western Australia (2006) 230 ALR 603, per Wilcox J, para [791] quoting the High Court in Members of the Yorta Yorta Aboriginal Community v Victoria (2002) 214 CLR 422.

[57] Brennan, S., Recent Developments in Native Title Case Law, Presentation at the Human Rights Law Bulletin Seminar: Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission, Sydney, 4 June 2007.

[58] Bennell v Western Australia (2006) 230 ALR 603, per Wilcox J, para [602]-[684].

[59] The Full Federal Court has already accepted a finding in the Western Desert case in South Australia (De Rose v South Australia No 2 (2005) 145 FCR 290) that a strict patrilineal system had given way to a more flexible one and that was consistent with the law set down by the High Court in Members of the Yorta Yorta Aboriginal Community v Victoria (2002) 214 CLR 422.

[60] Bennell v Western Australia (2006) 230 ALR 603, per Wilcox J, para [700].

[61] Or occurring between 1 January 1994 and 23 December 1996, if the act meets the definition of ‘intermediate acts’.

[62] Australian Bureau of Statistics, Australian Historical Population Statistics 2006, Table 18 , available online at: www.ausstats.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@archive.nsf/0/23F533BC3E26D892CA2571760022856F/$File/3105065001_table18.xls, accessed December 2006.

[63] Risk v Northern Territory [2006] FCA 404 (trial judgment).

[64] If you would like more detail on the case itself and a legal analysis of the decisions of the court, see National Native Title Tribunal, ‘Determination of native title – Larrakia’, Issue 19, Native Title Hot Spots, available online at www.nntt.gov.au/newletter/hotspots/, National Native Title Tribunal, ‘Appeal in Larrakia (Risk) – Full Court’, Issue 24, Native Title Hot Spots, available online at www.nntt.gov.au/newletter/hotspots/.

[65] Risk v Northern Territory and Quall v Northern Territory (2007) 240 ALR 75 (appeal judgment).

[66] The Larrakia asserted that their claim group encompassed two other claim groups’ applications – the Quall applicants and the Roman applicants. Quall and others were also a party to the case, representing the Danggalaba/Kulumbiringin clan. The Quall applicants also appealed to the Full Federal Court and their appeal was dismissed, however Quall has applied for special leave to appeal to the High Court and that application is still outstanding. The Roman applicants discontinued their claim. This case note will look at the case of the Larrakia people, as presented by Risk.

[67] Risk v Northern Territory [2006] FCA 404, per Mansfield J, para [17].

[68] Risk v Northern Territory [2006] FCA 404, per Mansfield J, para [3].

[69] Risk v Northern Territory [2006] FCA 404, per Mansfield J, para [839].

[70] Members of the Yorta Yorta Aboriginal Community v Victoria (2002) 214 CLR 422.

[71] Mansfield J, Summary of Risk v Northern Territory [2006] FCA 404, para [9] –[13].

[72] See for example, Jango v Northern Territory (2007) 159 FCR 531 per French, Finn and Mansfield JJ, para [85], where it was said: ‘It is true, as the appellants point out, that a native title determination is a judgment in rem which binds the whole world so that the issues at stake are not confined to the private interests of litigants.’

[73] Risk v Northern Territory [2006] FCA 404, per Mansfield J, para [811] echoing the words of Gleeson CJ and Gummow and Hayne JJ in Members of the Yorta Yorta Aboriginal Community v Victoria (2002) 214 CLR 422 at para [83].

[74] Risk v Northern Territory [2006] FCA 404, per Mansfield J, para [816].

[75] Risk v Northern Territory [2006] FCA 404, per Mansfield J, para [820]-[822], [812], [835].

[76] Risk v Northern Territory [2006] FCA 404, per Mansfield J, para [533]-[542], [543]-[554], [555], [556]-[559] and [560]-[570].

[77] Risk v Northern Territory [2006] FCA 404, per Mansfield J, para [571]-[577], [578]-[581], [582]-[585], [586]-[593], [594]-[598].

[78] Risk v Northern Territory [2006] FCA 404, per Mansfield J, para [599]-[624], [625]-[628], [629]-[631], [632]-[645], [646]-[647], [648]-[666], [667]-[673], [674]-[677], [678].

[79] Risk v Northern Territory [2006] FCA 404, per Mansfield J, para [680]-[699], [700]-[728].

[80] Risk v Northern Territory [2006] FCA 404, per Mansfield J, para [729]-[731].

[81] Risk v Northern Territory [2006] FCA 404, per Mansfield J, para [732]-[735], [736]-[737], [738]-[793].

[82] It should be noted that Quall also appealed the decision, but on different grounds. He claimed that Mansfield J failed to consider the substance of the case advanced by the Danggalaba/Kulumbiringin clan, that he failed to identify the relevant society that was the source of the traditional laws and customs, and that he failed to provide proper reasons for his decision. The Full Federal Court dismissed the appeal concluding that the case ‘was in substance disposed of on the basis of insufficiency of evidence. [Justice Mansfield’s] reasons make quite plain where that insufficiency law’. See Risk v Northern Territory and Quall v Northern Territory (2007) 240 ALR 75, per French, Finn and Sundberg JJ, para [178]. See also National Native Title Tribunal, ‘Appeal in Larrakia (Risk) – Full Court’, Issue 24, Native Title Hot Spots, available online at www.nntt.gov.au/newletter/hotspots/.

[83] Members of the Yorta Yorta Aboriginal Community v Victoria (2002) 214 CLR 422.

[84] Risk v Northern Territory and Quall v Northern Territory (2007) 240 ALR 75, para [83].

[85] Risk v Northern Territory and Quall v Northern Territory [2007] 240 ALR 75 [103 - 104].