Our future in our hands (2009)

Archived

You are in an archived section of the website. This information may not be current.

This page was first created in December, 2012

"Our future in our hands" -

"Our future in our hands" -

Creating a sustainable National Representative Body for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples

Report of the Steering Committee for the creation of a new National Representative Body

2009

Download in Word [2.25MB]

Download in PDF [1.72MB]

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Section 1: The importance of a National Representative Body

- Section 2: What we heard in the national consultation process

- Section 3: The proposed model: a new National Representative Body for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples

- Section 4: A developmental approach: the interim process for the new national representative body to December 2010

- Section 5: A generational view: The National Representative Body into the long term

- Section 6: Recommendations to government

- Attachment 1: An overview of the consultation process

- Attachment 2: Summary – Outcomes of national workshop on the establishment of a new National Representative Body for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, March 2009

- Attachment 3: Extract from report on the outcomes of the first phase of consultations for a National Indigenous Representative Body – prepared by the National Indigenous Representative Unit, FaHCSIA, December 2008

- Attachment 4: Corporate governance and behavioural standards for the new National Representative Body

- Attachment 5: Closing the Gap in Indigenous Disadvantage – Diagram of COAG commitments and process

- Attachment 6: Extracts from the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples

- Attachment 7: An overview of existing peak bodies, advisory councils and regional mechanisms

- Attachment 8: Terms of reference for Steering Committee for consultation process

- Attachment 9: Acknowledgements

“The discussion about a new National Representative Body is about our place at the table in making the decisions that impact on our communities, on our men, our women and our children.

It is about creating a genuine partnership with government and across society:

- With shared ambition, so we are all working towards the same goals and not at cross purposes.

- With mutual respect, so we are part of the solutions to the needs of our communities instead of being treated solely as the problem.

- With joint responsibility, so that we can proceed with an honesty and an integrity where both governments and Indigenous people accept that we each have a role to play, and where we each accept our responsibilities to achieve the change needed to ensure that our children have an equal life chance to those of other Australians.

- With respect for human rights, that affirms our basic dignity as human beings and provides objective, transparent standards against which to measure our joint efforts.

Let the new Representative Body set the vision for our people’s future, provide the guidance to achieving this and advocate for understanding for the consequences that flow from our status as the First Peoples of this nation.

My hope is that a new National Representative Body will operate in such a way as to inspire and support our people, while also holding governments accountable for their efforts, so we may ultimately enjoy equal life chances to all other Australians.

The first step on this road is mutual respect and a partnership. A National Representative Body is an essential component of achieving the long overdue commitments to closing the gap.”

Introduction

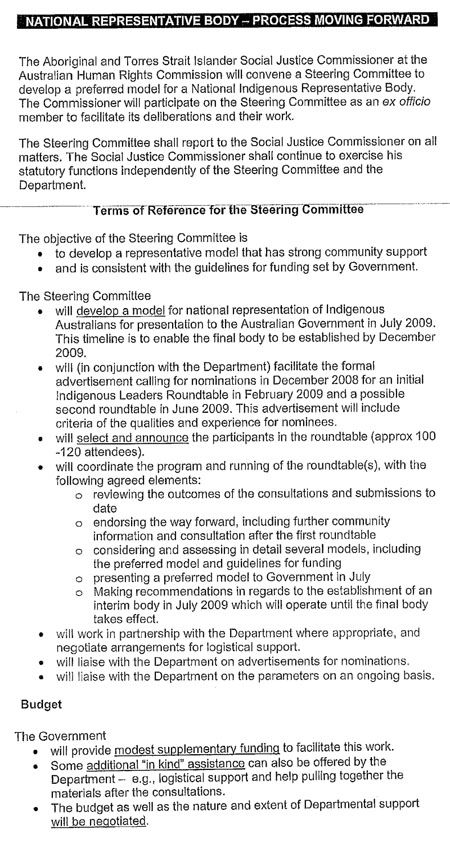

In December 2008, the Australian Government requested that, in my capacity as the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner, I convene an independent Steering Committee of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to develop a preferred model for a National Representative Body for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

The Steering Committee’s task was to:

- develop a preferred model for a new national Indigenous representative body for presentation to the Australian Government in July 2009;

- make recommendations in regards to the establishment of an interim body from July 2009 which would operate until the finalised body takes effect; and

- ensure strong community support for such a representative model.

This work was to build on the consultations and submissions process conducted by the Government in 2008.

In undertaking our task, we have used a mix of the usual and the not so usual techniques. Most notably, we convened a workshop of 100 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in Adelaide in March 2009, where every participant was selected through a merit based process. Since that time we have convened focus groups, conducted a national survey and national naming competition, as well as participated in workshops and meetings, and received written submissions.

This is the final report of the Steering Committee.

It recommends a model for a new National Representative Body for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

It sets out a vision of the substantial contribution that we hope the new National Representative Body will play over the next generation in order to ensure that our cultures and our human rights are respected and protected, and so that our children can truly enjoy equal life chances to all other Australians.

We have taken as our guiding principle Article 18 of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. It states:

Indigenous peoples have the right to participate in decision-making in matters that affect their rights, through representatives chosen by themselves in accordance with their own procedures, as well as to maintain and develop their own Indigenous decision-making institutions.

The Steering Committee has been encouraged by the consistent messages that we have heard through the course of the consultation process. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples understand the critical need for a new National Representative Body but they do not want a return to old ways.

We have constantly heard the message that our people want a robust national body that has integrity and displays the highest degree of professionalism in all of its operations. And they want the body to be sustainable – here for the long haul and ‘government proof’.

Something that we have continually heard in the consultation process has been the need for the National Representative Body to exhibit the highest standards of ethical and corporate behaviour. We have been encouraged by the positive response to the use of the Nolan Committee Principles on public life being built into the organisation’s structure.

There has also been broad agreement on the need for merit based selection processes to underpin selection processes. This is to overcome the problems of the past, where unqualified democratic processes have not served us well as peoples. We address these issues in the model that we are proposing, with a strong emphasis on ethical behaviour built into the operating structure of the organisation.

From the beginning of the consultation process there has been overwhelming support for a new National Representative Body to be independent of government. Independence from government will enable the body to fulfil its advocacy function in a bold and robust manner.

We have also been encouraged by recent actions of the Australian Government that set the scene for the new National Representative Body. Since the consultation process began, the Government has:

- Made substantial commitments to ‘closing the gap’ on disadvantage and marginalisation experienced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. This has also been agreed by all state and territory governments through the Council of Australian Governments. It sets a framework for a new partnership and relationship, and provides a central reference point for which all Australian governments are to be held accountable.

- Endorsed the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. This step was described by Minister Macklin as an ‘important step in re-setting the relationship between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians and moving forward towards a new future’ and as providing us with ‘new impetus to work together in trust and good faith to advance human rights and close the gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians.’

The groundwork has been laid for a new relationship – one based on respect and equality.

The National Representative Body is crucial in leading efforts to make these commitments and aspirations meaningful for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

As we have consistently heard through the consultations, ‘closing the gap’ is fundamentally linked to the recognition of our human rights. The gap will not be closed without our rights being protected and without our involvement in the process. We have tried to capture this message in the statement of mission and objectives for the new National Representative Body.

Ultimately, we have proposed that the new National Representative Body start small and be streamlined. It should have an initial development phase that lasts until the end of 2010 that is focused on building a strong governance and accountability framework, and importantly, on building buy in and acceptance of the model by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

Of critical importance in this initial phase will be ensuring that the new National Representative Body is adequately funded and has the financial structure to be sustainable into the longer term. Government has special responsibilities in this regard and it is expected that it will make the overwhelming contribution in the initial period. This would contribute to the sustainability of their current investment in closing the gap.

We have not proposed that the new National Representative Body have state or regional level structures. Instead, we propose that it operate in a way that provides for structured and transparent engagement at the regional and jurisdictional level, with regular opportunities for large groups to engage in policy setting and to hold the body accountable.

We also see the relationship between the new National Representative Body and existing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander representative bodies and peak bodies as critical to the long term success of the body. We have proposed that the body be structured in a way that can maximise the contribution of these bodies in order to create greater leverage and coordinated effort.

We anticipate that one of the key benefits of the new National Representative Body will be to provide a space where the existing sectoral or regionally specific expertise and knowledge of existing organisations can be harnessed for the greater good of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples at the national level. The role of the National Representative Body is to ‘value add’ not to replace this expertise. It should aim to draw sectoral interests into a lucid and overarching national strategy.

We also anticipate that the body will grow and evolve over its initial years. Processes for engagement and representation associated with the new National Representative Body will take time to build. This in part is due to the diverse cultures, languages and aspirations of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples – different structures and forms of engagement will need to be developed for different regions and situations.

Representative and advisory structures that currently exist will also need to change so that they are truly representative if they are to play a substantial role in the new National Representative Body.

For example, the Steering Committee sees most existing state and territory level advisory committees as they are constituted as lacking the necessary independence and representative status. We see a role for the new National Representative Body in encouraging the creation of more robust state and territory mechanisms into the future.

The task of creating a new National Representative Body is an enormously complex and challenging one. We have taken the first difficult step. There will be many more to come over the next few years.

I personally want to thank the members of the Steering Committee for their dedication and substantial contributions to this process. You have each had to show leadership and bravery in putting forward a bold vision for the future of our people.

Thank you also to the Committee’s Secretariat for your tireless efforts. The Secretariat was based at the Australian Human Rights Commission and benefited from the contributions of many staff of the Commission over the course of the project. My thanks to the President of the Commission, the Hon Catherine Branson, for her support as we have progressed with advancing one of the most significant processes to protect the rights of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples into the future.

Thank you also to our advisors and consultants, many who offered their support on a pro-bono basis and at extremely short notice. And thank you to the staff of the National Indigenous Representative Body Unit at the Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs for the substantial contribution that you have each made in order for us to reach this point.

All contributors to this process are acknowledged in Attachment 9 to this report.

Can I also thank Minister Macklin and the Australian Government for entrusting the Steering Committee with this important responsibility.

I also acknowledge the role that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander media outlets have played in spreading the word and ensuring that our peoples are informed about the consultation process.

An important acknowledgement also goes to Darren Dick and Josephine Bourne for drafting this comprehensive report in such a readable form.

And finally, I thank every Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander person who has contributed to the process. I hope that we have given true expression to your aspirations and desires for the future.

This is a rare opportunity for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples to work together with governments, industry and the Australian community to secure the economic and cultural independence of our peoples, and to enable us to truly experience self-determination, for the first time in this country.

I encourage all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples to get behind the new National Representative Body and to make it yours. As the title of this report states, let’s put ‘our future in our hands’.

TOM CALMA

Chair - Steering Committee for the creation of a new National Representative Body

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner

Section 1: The importance of a National Representative Body

The Steering Committee has chosen to commence its report by identifying why the National Representative Body is important.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples hold a unique place in our history and as first nations people have a fundamental contribution to make to ongoing national development and identity. A national body is a prerequisite to enabling this contribution through partnerships with government, the private sector and the Australian community.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples also have profound understanding of the consequences of racism and marginalisation and have essential insights and knowledge required to address the disadvantage which has resulted. The nation needs a body able to marshal this knowledge and contribute it to national policy and strategy.

Why is a National Representative Body important for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples?

Throughout the consultation process it has been clear that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples want a new National Representative Body.

A new National Representative Body is critical to provide Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples with a national voice. Our people have been without such a voice for five years. We have suffered as a result.

A new National Representative Body will enable the goals, aspirations, interests and values of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples to be heard in national debate, as well as enabling the diversity of perspectives of Australia’s first peoples to be recognised.

The National Representative Body will have an essential role in advocating for the recognition and protection of the human rights of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. It will provide a mechanism to give meaning to and pursue the exercise of our rights, including those recognised in the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. This includes recognising our right to determine our political status and pursue our economic, social and cultural development.

A National Representative Body can empower and inspire Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples by enabling individuals and groups to participate in decision-making processes that affect us. The National Representative Body will enable us to inform and feel part of policies that affect our lives and those of our families and communities.

The National Representative Body can inspire change within our communities that is informed and driven by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. We want to work with government and other agencies in designing and applying solutions to the social problems faced by us on a day to day and generational basis. We want to work together to overcome the poverty, inequality and injustice faced by our communities.

We also see the National Representative Body as an important mechanism to assist government in shaping its approach and in holding them accountable for service delivery to individuals and communities. We have a role in partnering with government to ensure that services are delivered in a manner that is meaningful for our communities, and that appropriately recognises our social and cultural issues.

This includes by ensuring that there are adequate monitoring and evaluation processes in place to ensure that our communities are benefiting from services that are designed to assist us.

We face challenges that will take at least one and in some cases, two generations to solve, with many of the problems today having been generations in the making. We need to keep governments and the federal parliament focused over the longer term if we are to see real change in our communities. We aspire to achieve bi-partisan support for addressing the challenges faced by our communities over the longer term. We also note that sustainable progress will only occur when we own our own problems, solutions and control our own future.

While governments and many non-government organisations have endeavored to address the many problems of our people, it must be us that drive the solutions and anything short of this renders us passengers in our own development. This in turn leads to more dependency.

The National Representative Body also has a critical role to play in supporting inter-generational dialogue among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. This can build a shared journey and vision between our generations to ensure that we plan for the future and nurture our future Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander leadership. Today’s leaders should aim to leave a lasting legacy for future generations of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people by ensuring that their rights to self- determination and their status as Australia’s First Peoples’ are recognised and protected.

For the National Representative Body to contribute in these ways it must always remember that it is accountable to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. The Body will need to ensure that it operates openly and transparently, maintains high standards of ethical conduct and good governance, and is inclusive for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

It will need to be proactive and focused on setting forth a positive vision to improve the well being of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. It must earn respect among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples rather than demand it.

Text Box: What do Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people see as important for the National Representative Body?

“...the National Representative Body should primarily act as an advocacy and negotiation body, arguing independently from a considered and well researched base, for the domestic implementation of the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and other relevant and binding human rights provisions...”(Public Submission 2)

“In order to make progress in the arena of Social Welfare Reforms we need to start taking several steps backward in order to gain momentum to move forwards. Formation of an Indigenous Peak Body on a national level will provide Indigenous people Australia wide with a vehicle allowing them to express positive and negative community needs and concerns which in turn empowers each individual and community as whole in regard to “Community Restoration.” (Public Submission 7)

“The outcomes must be our own and we cannot feel like our funding will be cut if we stand up and speak out against a government policy or program.” (Public Submission 8)

“The representative body should be held accountable for their time, actions and any decisions they make on behalf of the Aboriginal people of our land. For the representative body to be a true voice for Indigenous Australians they need to be able to hear what it is the Aboriginal people want and or need...” (Public Submission 44)

“Any national body should collaborate effectively with the Indigenous Dialogue – the Dialogue should be the key vehicle to facilitate constitutional reform and that this process be carried out under the principles of the UN Declaration such as free, prior and informed consent” (Public Submission 77)

“We need a balance of young people as representatives on our peak body also. It's always easy to presume we know best for our kids, but don't take the time to ask. I would like to see a balance of 50/50 men and women represented.” (Public Submission 16)

Why is a national representative body important for Australian Governments?

Australian governments continue to struggle with the intensely difficult task of addressing the marginalisation and disadvantage experienced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Too often, governments lack the cultural competency to engage appropriately with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, and laws and policies can add further to the harm experienced by communities.

The marginalisation and disadvantage experienced is entrenched and has affected Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples across generations. As successive reports have told us, most recently the 2009 edition of the Overcoming Indigenous Disadvantage Report[1], it is difficult to make sustained progress and there has been very little change in the position of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples relative to the rest of the Australian community in recent years.[2] With a substantial and growing youth population among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, there will be significant demand on future Government services.

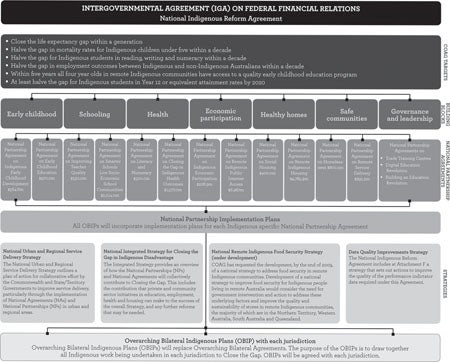

All governments in Australia want to see positive change that improves the lives of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Attachment 5 lists a series of commitments and statements made by Australian Governments that attests to this.

Most recently, the Council of Australian Governments (COAG) has made a series of commitments to closing the gap on key indicators of disadvantage experienced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

They have also commenced significant reforms to how financial relationships are managed between the Australian Government and state and territory governments. This includes through a series of new National Partnerships, Integrated Strategies and new approaches to Special Purpose Payments.[3] The Overcoming Indigenous Disadvantage framework has also been reformed to include regular assessments of progress in relation to the six closing the gap targets adopted by COAG.

Attachment 6 to this report provides an overview of the closing the gap process and commitments as agreed by COAG.

While the task is urgent, it will take considerable time for the COAG commitments and reforms to deliver sustained improvements in the livelihoods of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

It will require a sustained and consistent focus that governments have been unable to achieve to date. And it will require the translation of high level commitments into action at the community level that is meaningful and appropriately targeted to the needs of individuals, families and entire communities.

For this reason, governments will struggle in their efforts to make lasting progress in improving the conditions of our people and in our communities if there is not meaningful engagement with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

A National Representative Body is fundamental to any future action if we are to achieve positive change and close the gap.

There are three main contributions that the National Representative Body can make to the closing the gap agenda and in the relationship with government more generally. These are by:

- Providing the basis for a new relationship with governments – in order to reset the relationship based on partnership and genuine engagement with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples;

- Ensuring that there is a ‘shared journey’ between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and governments – with a shared ambition for the future that reflects the desires and aspirations of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, our families, communities and cultures; and

- Holding governments to account for their performance – in order to ensure governments remain focused over the longer term, with a clear understanding of their responsibilities and transparent accountability frameworks that remain relevant and targeted to the needs of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

Providing the basis for a new relationship with governments

There is an acknowledged need for governments to reset the relationship with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples based on partnership and genuine engagement.

The absence of an effective, credible National Representative Body in recent years has contributed to policy making at the national level being fragmented and uncoordinated, and developed without genuine engagement with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. As the Prime Minister stated in his Closing the Gap speech to Parliament in February 2009:

in recent years a sense of deepening despair had settled on much of Indigenous Australia. Many people felt they were not consulted; that decisions about their welfare were made without reference to them. That they had even become invisible to the nation.[4]

As the Social Justice Commissioner stated in the 2009 Mabo oration:

it doesn’t matter how magnificent a policy proposal is, how well crafted or clever it is, or how much money is attached to it. It will all amount to a hill of beans if it does not meet the ‘reality test’ of the livelihoods of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Nor will it be legitimate in our eyes.

We need to be the central players in our own development. Sustained prosperity and well being among our communities can only be achieved from building and supporting our capacity.

More than this, we have the right to determine the priorities for our communities and for our families.[5]

All Australian Governments, through COAG, have recognised the need to work in partnership with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples if they are to realise their Closing the Gap commitments. As they state in the National Integrated Strategy for Closing the Gap in Indigenous Disadvantage:

The Closing the gap targets are ambitious and work to achieve them will need to be undertaken over a considerable period of time... This will require... resetting of the relationship between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians. This reconciliation involves building mutually respectful relationships between Indigenous and other Australians that allows us to recognise our histories and our cultures.

Prime Minister Rudd has also emphasised the importance of a new partnership to closing the gap:

Fundamental to the Government’s strategy is a new partnership with Indigenous Australians. This partnership must be respectful and collaborative, and involve open communication with Indigenous Australians. Indigenous Australians have the capacity to bring about lasting change in their lives and those of their communities. Without a strong relationship with Indigenous Australians, based on mutual respect, mutual resolve and mutual responsibility, we cannot hope to close the gap.[6]

The National Representative Body provides a vital mechanism for creating this new partnership. COAG recognises this in the National Integrated Strategy for Closing the Gap in Indigenous Disadvantage:

COAG is committed to working in partnership with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to achieve the Closing the Gap reforms... Australia-wide consultations have been undertaken on the establishment of a national representative body to provide Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with a voice in national affairs... It is anticipated that it will be the primary mechanism for engaging on national Indigenous policy issues.

The creation of a National Representative Body will provide governments with a national focal point to provide expert advice on a holistic, whole of government basis. As can be seen from the model proposed, it is anticipated that it will have the ability to access expert advice across a range of issues.

It will also provide the ‘meeting space’ where Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and communities, peak bodies and interest groups will be able to focus on the bigger picture and set a longer term agenda for policy making and program delivery.

This will not absolve governments of the responsibility to engage and consult with communities on issues that affect them. It will, however, provide the starting point for discussions and set the broad directions for policy.

In resetting this relationship, we need to ensure that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander perspectives are front and centre of all relevant policy development processes. All government workers should have in the front of their mind the questions: does the policy I am working on impact (in a positive manner) on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples? Have I engaged with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples to reflect their perspectives on this issue and to identify the pathway forward?

For example, the Native Title Report 2008 discusses in detail the challenges that climate change and water resources create for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Our voices in these processes to date have been marginal at best. This is despite significant potential for strategies to mitigate the effects of climate change creating or supporting economies for our peoples or alternatively, for our traditional practices to be severely impacted upon by mitigation strategies.

The critical importance of ensuring our engagement in the climate change debate is but one example of what needs to occur if we are to reset the relationship in good faith.

Ensuring that there is a ‘shared journey’ between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and governments

Too often, policy and programs are developed and applied to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples without our involvement. This can result in policy approaches that miss the mark, or which are simply misguided or sometimes irrelevant to our circumstances and needs.

As Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, we have a legitimate stake in government activity that affects our lives. And we ultimately bear the responsibility to our families, our communities and to our ancestors.

The ‘Close the Gap’ approach initially emerged from the Social Justice Report 2005 of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner. It was championed and lobbied for by the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health sector, working with mainstream organisations and human rights NGOs.

Despite this, the Closing the Gap agenda that has now been agreed through COAG has been developed with limited participation and engagement with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. There is a pressing need for the Closing the Gap agenda to become a shared agenda between governments and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

COAG has acknowledged this as a concern. In the National Integrated Strategy for Closing the Gap in Indigenous Disadvantage they state:

To date, engagement with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people on the development of the Closing the Gap agenda has been at a very broad level. Implementation of the National Agreements and National Partnerships... agreed by COAG across the health, education, housing, employment and service delivery spheres will require developing and maintaining strengthened partnership arrangements.

There are two main reasons for this.

First, for the ‘Closing the Gap’ approach to succeed it must respect and promote Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures. The National Integrated Strategy for Closing the Gap in Indigenous Disadvantage identifies the following dimensions to this. Efforts to close the gap should:

- ‘build on the strengths of Indigenous cultures and identities’;

- reduce social exclusion of Indigenous peoples by ‘promoting and supporting a strong and positive view of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander identity’; and

- ensure that programs ‘meet the cultural needs of Indigenous people’, are focused on eliminating overt and systemic discrimination, and ensure that governments have the cultural competency and cultural awareness to implement programs effectively.

Addressing these issues is essential if services are to be accessible and to achieve the intended outcomes, and for them to be relevant and meaningful for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

Second, a ‘shared journey’ between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples with governments and the broader community is essential for a reconciled nation. As the text box on the Australian Reconciliation Barometer (in the next section below) shows, there is a clear desire among the Australian community for ‘shared pride’ in the cultures and histories of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

There is a lesson for all Australians in the Apology beyond its specific recognition and condemnation of forcible removal practices. It showed, for just one day, what a united Australia looks like when we squarely acknowledge our history and share our pain. It showed that ultimately, whether you are an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander person, or not, our futures are inextricably bound together by the common threads of dignity, respect and hope. A ‘shared journey’ is about nation building and a respectful future.

Holding governments to account for their performance

Australian governments, especially through COAG, have a history of making commitments to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples that have not subsequently been met. Commitments have never been matched by the necessary action (in human, technical and financial terms) to address the level of need in the community.

As the extract below from the Overcoming Indigenous Disadvantage Report 2009 shows, there remain significant problems in how governments are performing on issues relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. This includes through inadequate data collection, a lack of evaluation of projects and programs, and ‘inadequate policy development’ processes.

As successive Social Justice Reports have shown, existing policy processes relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples do not meet the standard of evidence based policy.[7] They also tend to not meet the key elements by the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet and the Australian National Audit Office in their Better Practice Guide to Implementation of Programme and Policy Initiatives.[8]

Recent developments at the Council of Australian Governments have seen the introduction of stronger accountability frameworks. This includes through National Partnerships and Integrated Strategies that have been adopted.

Despite this, there is a clear need for governments to be held accountable for their performance on issues relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples against agreed targets.

Governments do not have sole responsibility for the well-being of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. But they do have substantial responsibilities for the delivery of services.

Since the abolition of ATSIC, which only had a supplementary funding role, governments have been solely responsible for administering the delivery of services to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples (including through the use of community controlled and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander organisations). This will continue with the new National Representative Body not taking on these responsibilities.

The National Representative Body will play a critical role in holding the federal government to account for its performance.

This does not necessarily mean that the Body will itself conduct the monitoring and evaluation activities. Its role is more likely to be to ensure the presence of, and contribute to, mechanisms to monitor and evaluate government performance to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

Text Box: What do recent reviews tell us about the performance of the Australian Government on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander issues?

Overcoming Indigenous Disadvantage Report 2009

This report was commissioned by COAG and is produced every two years to report on indicators contained in the Overcoming Indigenous Disadvantage Framework. The current state of progress is described in the overview of the report as follows:

Across virtually all the indicators in this report, there are wide gaps in outcomes between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians. However, the report shows that the challenge is not impossible — in a few areas, the gaps are narrowing. However, many indicators show that outcomes are not improving, or are even deteriorating. There is still a considerable way to go to achieve COAG’s commitment to close the gap in Indigenous disadvantage.

Overall, Indigenous people have shared in Australia’s economic prosperity of the past decade or so, with improvements in employment, incomes and measures of wealth such as home ownership. However, in almost all cases, outcomes for non-Indigenous people have also improved, meaning the gaps in outcomes persist. The challenge for governments and Indigenous people will be to preserve these gains and close the gaps in a more difficult economic climate.[9]

The report considers that improving the ‘governance of government’ is key to achieving improved outcomes. It emphasises that engagement by governments with Indigenous communities is essential to achieve measurable improvements in economic, health, and social indicators.

Among the success factors identified in the report are:

- cooperative approaches between Indigenous people and government;

- community involvement in program design and decision-making;

- good governance — at organisation, community and government levels;

- ongoing government support — including human, financial and physical resources.

The report also notes that formal, public evaluation of Indigenous programs is:

hampered by inadequate data collections and poor performance information systems. For example, there is limited information on the use of mainstream services by Indigenous peoples and very little information on the barriers to access and use of services that Indigenous people face.

The Chairman of the Productivity Commission described the situation as follows:

While good governance has been lacking in many Indigenous communities, it has also been lacking within government itself. This is partly a legacy of divided jurisdictional responsibilities, and partly due to ‘silo-based’ approaches to service delivery and policy development within individual administrations. The result has been a staggering lack of coordination in service delivery, inadequate policy development and program evaluation, and a surfeit of redtape — all of which have contributed to poor outcomes and a lack of capacity to take corrective action when things go wrong. [10]

Report of the Northern Territory Emergency Response Review Board 2008

This review considered progress in implementing the Northern Territory Emergency Response (or NT intervention). It noted progress in some areas, accompanied by substantial problems. The Board noted that:

Support for the positive potential of NTER measures has been dampened and delayed by the manner in which they were imposed. The Intervention diminished its own effectiveness through its failure to engage constructively with the Aboriginal people it was intended to help.

The Review Board particularly emphasised the need to reset the relationship between Aboriginal peoples in the Northern Territory and government:

One thing is very clear to the Review Board: the way forward from the Intervention can not be based on a return to 'business as usual'. Both Aboriginal people and the Australian Government want a new relationship.

The most fundamental quality defining that relationship must be trust. And for that to occur at the community level in the Northern Territory there must be an active re-engagement with the community by government.

Accumulated neglect by governments over 30 years has resulted in situations within some remote communities that could benefit from the same disciplined, professional approach that Australia brings to international programs of reconstruction and community development. If it is to work, community development must be led by the community and partnered by government. That is the basis for a new relationship.

It is a relationship governed by principles of informed consent, participation and partnership. It will require structural support enabling robust and sophisticated dialogue, where common aspirations can be explored and regional and local agreements can be negotiated.

The Review Board recommended that:

- The Australian and Northern Territory Governments endorse the need to reset the relationship with Aboriginal communities in the Northern Territory and move in partnership to develop and maintain a community development framework within which a genuine engagement with communities can develop and be maintained.

- Both governments commit to the reform of the machinery and culture of government to enable a more effective whole-of-government approach to be delivered on the ground and to support professional development for their key personnel located in Indigenous communities.

Why is a National Representative Body important for industry and for Australia?

A National Representative Body will not just be of benefit to government and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. It will provide a focal point for industry and also benefit the Australian community more broadly.

Increasingly, the corporate sector is seeking to connect their business activities to the communities in which they operate. Initiatives like Reconciliation Action Plans and the Employment Covenant show that the corporate sector, unions, sporting codes and non-government organisations want to play their part in closing the gap and in promoting reconciliation.

This is good for business, while also having the potential to promote social cohesion and provide reputational benefits to companies for their corporate social responsibility.

But many in the corporate sector struggle to identify what role they can play or do not have the necessary cultural competencies. This can result in failure to achieve outcomes, a lack of confidence and a reluctance to take action.

The National Representative Body has the capacity to play an authoritative role in advising industry and others, and to build partnerships that benefit Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and communities. With ownership of 20% of the landmass, knowledge of country and environment and a growing labour force, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have a high stake in economic development. A National Representative Body can facilitate that development by assisting industry to understand how to do business with our people.

The Australian Government has explicitly identified the role of the business and philanthropy sectors as crucial to achieve the Closing the Gap agenda:

The challenge we now confront is to work together to close the gap in real life outcomes between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians. This is the objective to which the Australian Government is committed, but cannot achieve on its own. As a nation, we must come together around this vision and take substantive action – Indigenous and non-Indigenous people, Commonwealth, state and territory governments, business and the wider community.

The experience of previous efforts to close the gap demonstrates that achieving our targets in this area will require commitments from the broader corporate and community sectors. The forging of corporate and philanthropic partnerships with Indigenous communities will help to deliver real and sustainable results.[11]

It is envisaged that over time, the corporate and philanthropy sector will also play a major role in assisting the National Representative Body in becoming financially sustainable. They may also purchase services from the National Representative Body, such as advice.

The text box below provides an overview of the main findings of the Australian Reconciliation Barometer, which seeks to measure the strength of the relationship between the broader Australian community and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

It identifies a common willingness for there to be a relationship and a desire to develop a shared pride in the cultures, histories and traditions of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. But it also reveals a lack of trust and understanding between the two groups.

The National Representative Body has the potential to lead efforts to build trust and understanding, and to bind all Australians together in celebrating Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures.

Text Box: The Australian Reconciliation Barometer

In 2009, Reconciliation Australia published the first Australian Reconciliation Barometer.[12] The Barometer is a national research study that looks at the relationship between Indigenous and other Australians. Designed to be repeated every two years, the Barometer explores how we see and feel about each other, and how perceptions affect progress towards reconciliation and closing the gaps.

Some of the key findings that are of relevance to the National Representative Body are as follows.

Importance of relationship

Indigenous and other Australians agree that the relationship between us is important. Although we agree the relationship is important, we don’t trust each other and this affects how we think, feel and act.

Indigenous and other Australians see many things about ourselves very similarly and in line with how we see the Australian identity. The research shows both Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians agree it’s important to learn about Indigenous history and culture. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are open to sharing their history and culture, and want all Australians to take pride in it. Other Australians want to know more but are afraid to ask. Once again, lack of trust discourages us from acting on our inclinations to share.

Australians want to have more contact with Indigenous people and to contribute to closing the gaps but they don’t know how to go about it. Again, lack of knowledge and trust makes non-Indigenous people hesitant about reaching out. For many, so does their fear that it’s all too hard.

Quality of the relationship

There is a remarkable level of agreement between Indigenous and other Australians about the quality of the relationship.

Only about half of either population group agree that either the relationship between Indigenous and other Australians today is good or that the relationship between Indigenous and other Australians is improving. This suggests that, despite a common belief that the relationship is important, there is a long way to go in improving the relationship.

The responses also point to a critical factor in any relationship – the level of trust. Only about 1 in 10 people feel there is a high level of trust in the relationship, with Indigenous people feeling this way about other Australians and other Australians about Indigenous people.

Shared pride

One of the cornerstone conclusions of this study is the scope for a greater sense of shared pride in key aspects of Indigenous life in Australia - the people, their history and cultures.

Only 44% of the overall population believe that Indigenous people are open to sharing their culture with other Australians. But 89% of Indigenous people say they are open to sharing their culture.

This indicates a significant gap in perceptions and suggests that one important way to close this gap is to support Indigenous Australians in finding ways to share their culture with non- Indigenous people, and to support non-Indigenous Australians in finding ways to learn about, experience and take pride in Indigenous culture.

Section 2: What we heard in the national consultation process

The Steering Committee has benefited from an extensive consultation process. This has significantly shaped the perspectives of the Committee and the ultimate model that it has proposed in this report.

This section provides a summary of the main issues raised during the final round of consultations undertaken by the Steering Committee from April 2009. It includes information from:

- Focus Groups convened nationally, May – June 2009;

- National Survey – conducted online, May – July 2009;

- Submissions; and

- Consultations, workshops and meetings convened or attended by the Steering Committee.

This constituted the third stage of consultations for the process. The previous stages were:

- The convening of a national workshop of 100 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples on the establishment of a new National Representative Body in Adelaide in March 2009; and

- The conduct of a first round of consultations conducted by the Australian Government in 2008.

Each stage of the consultations has been more specific and detailed than the stage that preceded it.

Information about the previous two rounds of consultations is included in Attachments 1 – 3 of the report. Information about these previous stages has been publicly available for some time, and has framed the discussions for the third and final stage of consultations.

There is a need for a new National Representative Body

Throughout the consultation process, there has been broad and consistent support for the establishment of a National Representative Body for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

Terminology

There was very little support for retaining use of the phrase ‘Indigenous peoples’ as the main terminology at the national level. The majority view expressed was for the phrase ‘Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’, with a significant number also preferring the terminology ‘first nations/first peoples’.

Role of the National Representative Body

There is a clear expectation that the National Representative Body will focus on the big strategic national issues and should not be involved in lesser issues or be excessively involved in service delivery related issues. There was near universal support for the body not being directly involved in service delivery or allocation of Government funds.

There was support for the National Representative Body to:

- Play a leading role in developing new partnerships between Indigenous peoples and governments;

- Contribute to and lead policy development on Indigenous issues;

- Provide an Indigenous perspective on issues across government;

- Advocate for the recognition and protection of Indigenous peoples’ rights;

- Ensure accountability mechanisms for government service delivery are adequate;

- Ensure that Close the Gap commitments are supported by long term national action plans;

- Support good governance among Indigenous communities and organisations; and

- Ensure equal participation of Indigenous women in governance and decision-making processes.

The following were identified as the most important roles for the National Representative Body:

- Advocacy.

- Provide policy and advice.

- Monitor government service delivery.

- Negotiate framework agreements with governments.

Structure of the body

The majority view was that the body needs to be streamlined and cohesive in order to be effective. This position was, for many, contingent upon there being:

- Structured and transparent engagement at the regional and jurisdictional level

- Regular opportunities for large groups to engage in policy setting and to hold the body accountable (such as through annual conferences).

There was a considerable majority who believed that the National Representative Body will need an active process for grounding its thinking in local/regional knowledge and views and would need broad forums to canvas policy views and to provide an accountability mechanism.

There were, however, differing views about how to achieve this. In particular, there were differing views on whether the National Representative Body would require structures at the regional and state/territory level or whether it should rely on processes for engagement at these levels.

Many believed that a formal membership structure is not essential at this stage and that the National Representative Body needs to utilise and engage with existing structures and processes rather than create new structures.

Many believed that the National Representative Body needs clear, robust and transparent relationships with regional and local groups but does not need to formalise this in order to be credible and effective.

Many people saw that regional involvement should be focused upon the importance of ongoing engagement to ensure informed positions are adopted and for accountability purposes.

Role of experts and peak bodies

There was a strong view that the National Representative Body should have access to expert knowledge. However, there was not widespread support for peak bodies to provide this directly through having a representational role.

There was, however, strong support for the National Representative Body to provide a ‘meeting place’ for peak bodies and for them to be involved in the working processes of the body.

Gender equality

There was strong support for equal representation of women in any structure for the new National Representative Body – however it is constituted. This should not displace appointment processes that are based on merit.

Representation of Torres Strait Islanders living on the Mainland

There was strong support throughout the consultation process for mainland Torres Strait Islanders to be treated equitably in the National Representative Body.

During consultations with both Torres Strait Islander representatives from the region and those living on the mainland, it was expressed that mainland Torres Strait Islanders’ representation on the National Representative Body should come from a new body or association of mainland Torres Strait Islander people.

There was also common agreement from both groups that it should be recognized nationally that all Torres Strait Islander peoples are connected back to the Torres Strait Island region and have shared histories, customs and cultures.

The importance of integrity and merit

There was general agreement that the National Representative Body will need to act with integrity in order to build its legitimacy with the community, the political world or the non Indigenous community.

This means that the individuals involved need to bring personal integrity. There was also wide support for the ‘Nolan Principles’ as setting an ethical framework for the National Representative Body.

Appointment processes

There was very broad agreement that ‘merit’ (along with integrity) is vital to any appointment process for the new National Representative Body. This view was shared by those who thought that elections were an essential component of the process of appointment.

A minority believed that elections are essential to credibility. Where there is support for an election process, this was often accompanied by the view that elections should build in a review mechanism in order to appoint the most meritorious.

There was support for a delegate model[13] from those who sought to ensure that particular groups would be represented (e.g. Torres Strait Islanders on the mainland). There was also support for an electoral college model[14] to provide the legitimacy of elections but within a more controlled, less costly structure.

There was a broad consensus that key members of the body will need to be full time but divergence about whether all should be.

Relationship to government

The majority of people believed that the National Representative Body should have a strong relationship to the Australian Government as well as state and territory governments.

The majority of people saw that the body should ultimately exist separate from government and be focused on the interests of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

Most people saw an autonomous body emerging over time rather than being a direct outcome of this process.

The overriding concern was to ensure that the National Representative Body has influence over government policy and in reviewing government performance. Most participants also want to develop approaches which have the National Representative Body represented in key decision making forums not just making proposals.

Many people saw a statutory link to Parliament, mechanisms for reporting to parliament and working with a lead government Minister as a way of advancing this.

Funding

Many participants believe that Government should be obligated to fund the National Representative Body, at least in its initial years.

There is also widespread recognition that substantial operational autonomy will only be achieved with non government funding sources. There is considerable optimism that independent funding sources may become available over time, although it was widely expressed that it would take considerable time to build an autonomous corpus and or cash flow.

The main funding options identified for the National Representative Body were:

- Receiving untied government funding;

- Having a fund established to give the body a capital base (like the Indigenous Land Corporation);

- Being established with a future fund financed through a percentage of mining tax receipts; and

- Obtaining charitable status to receive tax-free donations and other concessions.

Interim Arrangements and first twelve months’ priorities

Feedback throughout the consultations identified the most important task for the National Representative Body at the outset being to establish and foster key relationships, particularly across peak bodies, governments, regions and the private sector. People expressed that it is particularly important for the National Representative Body to work with national peak and community bodies, as well as focusing on dialogue with governments to establish a clear and productive relationship from the beginning.

We also heard that in its interim phase the National Representative Body should continue the dialogue with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in order to develop a business model for the organisation. This should articulate the long-term vision into a series of clear statements of priority and strategy, with targets and benchmarks.

It was acknowledged that the National Representative Body should also take advice from a wide range of sources, extending beyond Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities and organisations. This includes by actively engaging with the private sector.

It was also proposed that the National Representative Body review existing accountability mechanisms for governments and identify potential reforms.

Two key tensions in designing a new National Representative Body

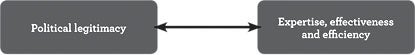

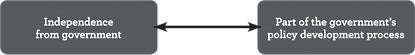

Two key tensions have emerged through the consultation process. These are represented in the following diagram.

Diagram: Two key tensions in designing a new National Representative Body

1. Representation Tension

2. Relationship with Government Tension

The first tension is a representational one – how does the National Representative Body obtain political legitimacy with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples while also being streamlined, cohesive and expert in its operations?

There was a clear message through the consultations that appointment processes for the National Representative Body should emphasise merit based selection to ensure that the Body has the right set of skills to perform its key roles. For some people, there was acceptance that a directly elected process may not produce this result. This was because some people who could make a substantial contribution to the National Representative Body may not nominate for appointment/election or may not be popularly endorsed.

Related to this is the tension about whether the role of the National Representative Body is to represent a national perspective on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander issues or to represent Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples across the nation. These are qualitatively different things. Answering this question goes to the size of the body and its formal structures, as opposed to its processes for engagement.

The second tension concerns the relationship to government. A key issue throughout the consultations was the desire for the National Representative Body to be independent from government (in particular, free of the ability of government to control or abolish the body) while also being influential with government and playing a key role in the policy development process.

The model proposed by the Steering Committee seeks to address these tensions.

Section 3: The proposed model: a new National Representative Body for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples

There is a clear need for a National Representative Body.

The Steering Committee is of the view that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are ready to begin the process of establishing the National Representative Body and for it to begin operating.

Further delay in establishing the Body will result in a continued lack of national voice and will damage the interests of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. We need to take action now to build momentum, while retaining the flexibility to adapt the Body’s structure as it develops.

Accordingly, the Steering Committee is proposing that:

- A National Representative Body be established as a non-government entity;

- There be an initial establishment phase lasting until the end of 2010 for the National Representative Body; and

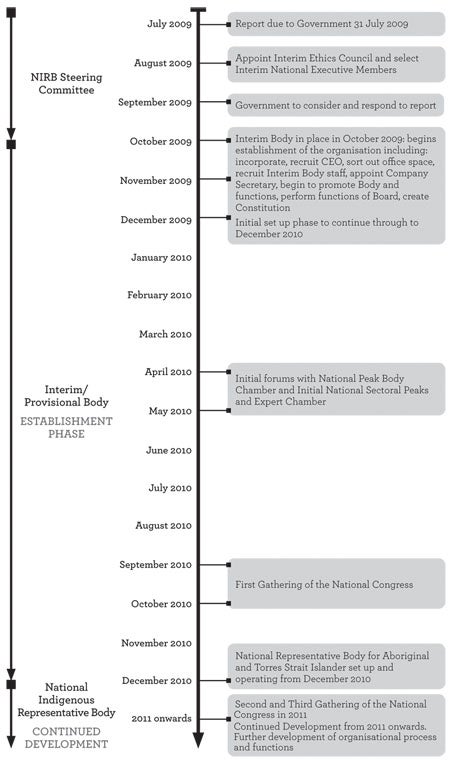

- The National Representative Body have the features as outlined below.

Section 6 of this report outlines what we see as the responsibilities of the Australian Government in relation to the establishment of the new National Representative Body and makes a series of recommendations to them.

A developmental approach

The National Representative Body should start small, with a focus on getting its corporate governance in place and in developing transparent decision making processes.

The Steering Committee has formed the view that this initial establishment phase will take approximately 15 months, and should run until the end of December 2010.

Section 4 of this report details the proposed activities of the National Representative Body in this development phase, including processes for appointment to the initial board and the transitional process to a more permanent structure.

As described further below, during this developmental phase the National Representative Body should utilise consultative mechanisms such as a national policy conference/Congress as the primary mechanism for participation and representation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. It should focus on building relationships with existing mechanisms and peak bodies to utilise the considerable existing knowledge and skills within the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander sector.

This is instead of forming regional and state/territory level structures.

Once the National Representative Body has found its feet, it will be able to consider mechanisms for supporting the development of more localised representative structures if desired by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

It is also proposed that the Australian Government will take a lead role in funding the initial stages of the National Representative Body. It is proposed that this funding be focused on three issues:

- Ensuring that the body has the necessary recurrent funding for its day to day operations;

- Building a corpus to ensure the sustainability of the body into the future; and

- Facilitating the fast tracking of approval for the Body to enjoy Charitable status.

This will enable the body to become financially secure and independent from government over time. This is discussed in more detail below.

Key features of the new National Representative Body

A company limited by guarantee

The new National Representative Body should be a private company limited by guarantee rather than a statutory authority.

As the title of the report suggests, this will place our futures in our hands.

The Steering Committee has consistently heard the aspiration of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples that the National Representative Body become self-determining over time. This cannot happen if the body is a creation of Parliament whose existence is dependent on the goodwill of Parliament and the government of the day.

A company limited by guarantee will also have the following advantages over a statutory model:

- The structures of the Body will be able to be flexible, with the members able to alter the Constitution when necessary. If the Body was a statutory authority it would have to rely on Parliament to approve such changes and may also have unnecessary or politically motivated changes foisted upon it.

- A private company is more likely to attract corporate and philanthropic support for its operations. This will particularly be the case if the Body has tax deductibility status (as recommended below). It is unlikely that a statutory authority – namely a government entity – would attract significant corporate support. This would leave the body dependent on government funding into the long term.

- A private company structure can begin immediately. While it will take a substantial amount of effort and time to fully establish the company and its governance procedures, there will still be greater certainty for the Body than if it is left to the processes of Parliament for its creation.

Mission/Objectives

The National Representative Body’s mission should be to provide national leadership in advocating for the recognition of the status of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as First Nations peoples, in protecting our rights and advancing the wellbeing of our communities.

The National Representative Body should do this by:

- Providing a representative voice and advocate for the best interests of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples;

- Actively pursuing a principled and visionary agenda to secure the economic, social, cultural and environmental futures of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples;

- Building a new relationship with government, industry and among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and communities, based on mutual respect and equality;

- Operating with the highest standards of professionalism and organisational integrity with processes that are transparent, participatory, informed and robust.

Guiding Principles

The following principles should guide the operations of the National Representative Body. It should:

- Enable and support Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples to be self-determining;

- Promote community building and sustainable development for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities;

- Operate independently and free from government influence/control;

- Demonstrate a commitment to the highest standards of ethical and moral conduct;

- Exhibit a strong performance-based culture, not risk-or conflict-averse, emphasising high levels of personal responsibility for exemplifying corporate values and behaviours among all staff;

- Be open, transparent and accountable to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples;

- Ensure equal participation of men and women in leadership and decision making;

- Promote the meaningful and effective participation of young people in recognition of their status as a majority in our communities and to ensure long-term succession planning;

- Ensure the participation of particularly vulnerable and marginalised groups, such as children and young people, people with disabilities, members of the stolen generations, people living in remote communities and homelands, and mainland Torres Strait Islanders.

- Understand that the challenges faced require a long term, inter-generational vision.

Roles and functions

The National Representative Body should have the following roles and functions:

- Formulating policy and advice – to ensure that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples contribute to and lead policy development on issues that affect us and that an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander perspective is provided on issues across government

- Advocacy and lobbying – to act as a conduit between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and the government, corporate and non-government sectors and ensure the acts of those sectors are in the best interests of Aboriginal and Torres Straits Islander peoples

- Ensures the presence of, and contribute to, mechanisms to monitor and evaluate government performance to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

Over time, the National Representative Body could also undertake roles in:

- Building coalitions that draw on the existing strengths and expertise of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and communities, and existing peak and representative bodies;

- Creating partnerships with government, industry and others – for example, through negotiating framework agreements;

- Conducting research and contributing to law reform processes;

- Representing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples at the international level;

- Ensuring government commitments, such as ‘closing the gap’ on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health, education and other areas of inequality, are supported by long term action plans;

- Acting as a ‘clearing house’ to promote the sharing of information between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander representative organisations and service delivery organisations;

- Conducting facilitation and mediation services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

Structure of the National Representative Body

Based upon the feedback from consultations the Steering Committee proposes an organisational model which strongly affirms a commitment to merit while also ensuring that the decisions of the National Representative Body are informed by and accountable to a carefully structured constituency. Further the body will have a strong, constitutionally recognised mechanism for managing ethics.

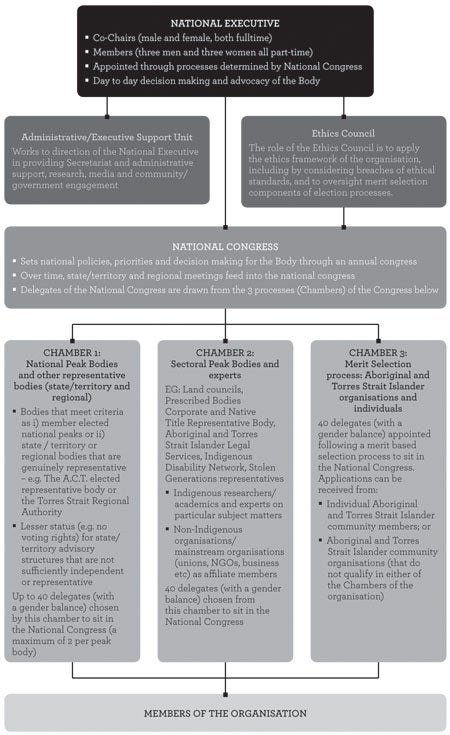

Diagram 1 below summarises the proposed structure of the National Representative Body.

It is proposed that the National Representative Body have four main components:

- A National Executive;

- A National Congress;

- An Ethics Council; and

- An Administrative or Executive Support Unit.

a) The National Executive

The National Executive will be the governance and operational arm of the organisation.

The executive will:

- Formulate, advocate and implement policies and priorities consistent with the decisions of the National Congress;

- Develop the strategic and business plans for the organisation;

- Organise and lead engagement strategies with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people;

- Direct the work of the Administrative/executive support team; and

- Communicate the views and policies of the organisation to stakeholders and the Australian public.

In order to carry out these functions the Executive will:

- Have a male and female Co-Chair, both of whom is full time; and

- Have six part time members, 3 men and 3 women.

It is proposed that all members of the National Executive be paid employees and have duty statements which detail the working requirements beyond the core governance functions fulfilled by attending meetings. It is the Steering Committee’s view that the part time members’ duties should include responsibilities to lead the chambers of the National Congress as follows:

- 2 members to chair the National Peak Bodies Chamber;

- 2 members to chair the Sectoral Peak Bodies/Expert Chamber; and

- 2 members to lead community consultation processes with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

The next section proposes a selection model for the establishment/ developmental phase of the National Representative Body up to December 2010. A proposed model for appointment is discussed further below.

It is proposed that the initial National Executive will clarify the process for appointment of the first permanent National Executive (to commence from January 2011).

The Steering Committee also recommends that all members of the Board should take on the following obligations:

- Commit to meet the ethical standards established for the organisation (including the Nolan Principles);

- Commit to undergo governance training within six months of commencing office (with failure to do so resulting in automatic suspension from the role)[15]; and

- Agree to formally mentor at least one young Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander person (to be selected from the membership of the National Congress).

b) The National Congress

The National Congress will be the primary accountability mechanism for the National Representative Body. It will set the national policies and priorities for the National Representative Body through its annual congresses. It will also elect the National Executive. Each Congress would also include an Annual General meeting of the organisation, and allow for other decisions relating to the constitution, structure and membership.

It is anticipated that, over time, state/territory level and regional meetings will be conducted to feed into the national congress.

The National Congress is intended to provide a forum to engage in national policy setting and to hold the body accountable. Governments will be invited to participate in the Congress as observers.

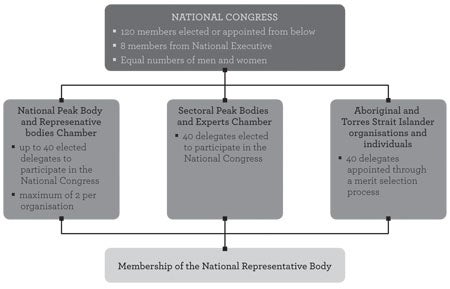

To ensure that the National Congress is able to operate effectively in its decision making capacity, it should be strictly limited in size. Initially it should be comprised of a maximum of 128 delegates with voting rights. This may grow over time.

It is intended that delegates in the National Congress will participate as individuals. They are there to contribute to a national collective perspective rather than to simply represent the organisation or state/territory that has nominated them or employs them in other capacities.

Other organisations and people not selected as delegates of the National Congress could still attend the congress meetings, but only in an observer capacity.

The 128 delegates would be determined through selection processes conducted every two years so that the National Congress is constantly refreshed with new perspectives. Diagram 2 below describes the selection process.

The 128 delegates of the National Congress would be determined as follows:

- Members of the National Executive would be entitled to sit in the National Congress. That is, the two full time Co-Chairs and six part-time members who are elected (in accordance with the process set out below). As per usual corporate practice, the two full-time Chairs will be chairing the National Congress and so would not be able to vote ordinarily – except in the case of a deadlock.

- A chamber of national peak bodies and other state, territory and regional level representative organisations would be created. A permanent Chamber would be set up to provide a regular forum for national peak bodies and state/territory or regional level representative bodies to interact.

The role of the chamber would be to a) nominate up to 40 delegates on the National Congress (with a maximum of 2 delegates from any one organisation, and with a gender balance of delegates)[16]; b) to prepare advice to the National Congress annually; and c) to provide advice on specific issues when requested by the National Executive or National Congress.