Track the History - Us Taken-Away Kids: commemorating the 10th anniversary of the 'Bringing them home' report

Archived

You are in an archived section of the website. This information may not be current.

This page was first created in December, 2012

Us Taken-Away Kids

Commemorating the 10th anniversary of the Bringing them home report

Track the History

This timeline focuses on one particular aspect of the history of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples - the forcible removal of Indigenous children from their families.

This material identifies some significant laws and practices that made removal lawful and includes writing and artwork from members of the Stolen Generations and their families which illustrate their experiences of these policies. This section uses as its primary resource Bringing them home, the report of the National Inquiry into the Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from Their Families. It also draws on documents and information from a wide range of others sources. The chronology particularly focuses on significant events and legal developments in the 10 years after the publication of the Bringing them home report, between 1997 and 2007.

A more detailed timeline, government responses to the 10th Anniversary and other information can be found on our website www.humanrights.gov.au/bth

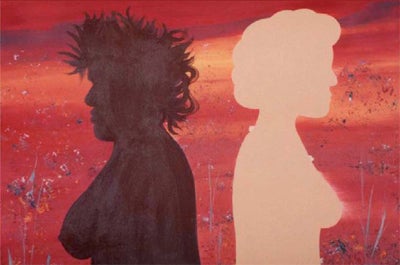

Painting: 'Coming Home' Beverley Grant, 2007.

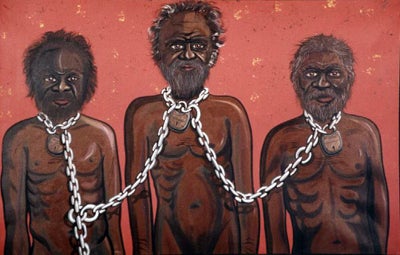

Painting: 'Colonisation' by Lawry Love, 2001.

.

1770

James Cook claims possession of the whole east coast of Australia. Cook raises the British flag at Possession Island, off Cape York Peninsula in Queensland.

1788

The First Fleet lands in Port Jackson - British settlement in Australia begins. Clashes between Aboriginal people and the settlers are reported over the next 10 years in the Parramatta and Hawkesbury areas outside the main settlement areas.

1830

Tasmanian Aborigines are resettled on Flinders Island without success. Later the community is moved to Cape Barren Island.

1837

The British Select Committee examines the treatment of indigenous peoples in all British colonies and recommends that ‘Protectors of Aborigines' be appointed in Australia.

1838

The Myall Creek Massacre, near Inverell (NSW). Settlers shoot 28 Aboriginal people, mostly women and children. 11 Europeans are charged with murder but are acquitted. A new trial is held and seven men are charged with the murder of one Aboriginal child. They are found guilty and hanged.

1869

The Aborigines Protection Act (Vic) establishes an Aborigines Protection Board in Victoria to manage the interests of Aborigines. The Governor can order the removal of any Aboriginal child from their family to a reformatory or industrial school.

1883

The NSW Aborigines Protection Board is established to manage reserves and the lives of 9,000 people.

1897

The Aboriginal Protection and Restriction of the Sale of Opium Act (Qld) allows the Chief Protector to remove local Aboriginal people onto and between reserves and to hold children in dormitories. Until 1965 the Director of Native Welfare is the legal guardian of all ‘aboriginal' children whether the parents are living or not.

Photograph: School, Mornington Island, 1950. Courtesy of the State Library of Queensland and the community of Mornington Island.

1901

Australia becomes a Federation. The Constitution states that Aboriginal People shall not be counted in the census, and that the Commonwealth has the power to make laws relating to any race of people in Australia with the exception of Aborigines. The federated states therefore retain exclusive power over Aboriginal affairs until the Constitution is amended in 1967.

1905

The Aborigines Act (WA) is passed. Under this law, the Chief Protector is made the legal guardian of every Aboriginal and ‘half-caste' child under 16 years old. In the following years, other states and territories enact similar laws.

1909

The Aborigines Protection Act (NSW) gives the Aborigines Protection Board power “to assume full control and custody of the child of any Aborigine” if a court finds the child to be neglected under the Neglected Children and Juvenile Offenders Act 1905 (NSW).

1911

Aborigines Act (SA) makes the Chief Protector the legal guardian of every Aboriginal and `half-caste' child with additional wide-ranging powers to remove Indigenous people to and from reserves.

The Northern Territory Aboriginals Ordinance (Cth) gives the Chief Protector powers to assume “the care, custody or control of any Aboriginal or half caste if in his opinion it is necessary or desirable in the interests of the Aboriginal or half caste for him to do so.” The Aborigines Ordinance 1918 (Cth) extends the Chief Protector's control even further.

1928

The Coniston Massacre, Northern Territory. Europeans shoot 32 Aborigines after a white dingo trapper and station owner are attacked by Aboriginals. A court of inquiry says the action of the Europeans' is ‘justified'.

1935

The introduction of the Infants Welfare Act (Tas) is used to remove Indigenous children on Cape Barren Island from their families. From 1928 until 1980 the head teacher on Cape Barren is appointed a special constable with the powers and responsibilities of a police constable, including the power to remove a child for neglect under child welfare legislation.

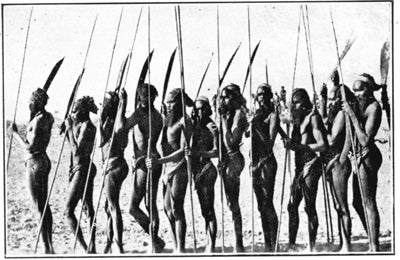

Photograph: Group of Warriors from the tribes west of Hermannsburg, Central Australia. Photographs of Australian Aborigines, Aborigine's Friends' Association, Adeleaide 1936. Courtesy of Ivan Copely.

1937

The first Commonwealth / State conference on ‘native welfare' adopts assimilation as the national policy: “The destiny of the natives of aboriginal origin, but not of the full blood, lies in ultimate absorption ... with a view to their taking their place in the white community on an equal footing with the whites.”

In 1951, at the third Commonwealth / State Conference on ‘native welfare', assimilation is affirmed as the aim of ‘native welfare' measures.

‘Group of Warriors from tribes west of Hermannsburg, Central Australia',

Photographs of Australian Aborigines, Aborigines' Friends' Association, Adelaide, 1936. Courtesy of Ivan Copely.

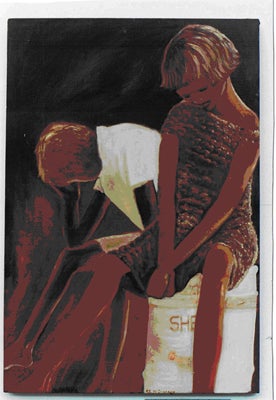

Painting: 'Leaving the Mission'. Beverley Grant, 2007.

Lake Tyres,

Aboriginal Station,

Aug. 14th, 1930.

Most Excellency Lord Stonehaven,

State Governor,

Canberra House, N.S.W.

I'm a full - blooded Aboriginal by birth decent from Royal Blood. I used to write letters to Queen Victoria in my young days. Your most Excellency, I beg to ask of his Excellency a great favour - would his Excellency kindly grant me permission to get my three grand - children who were snatched suddenly from me by an Ordering Council under escort of Nurse Singleton from Lake Tyres Aboriginal Reserve, transferred to the State Public Home, Melbourne. Three girls ages ranging from 13 years, 5¼ years, baby 2½ years Mary Darby, Sarah Darby and Nelly Darby. The three girls were my only comfort when their mother Lizzie Darby, my daughter, expired nine months ago at the Bairnsdalegate Hospital. When we came down to the town Captain Newman made a covenant with me in the presence of Patrol Walter M' Cready, that I could have the three grand - daughters till such time I'd be married. On the eve of my marriage to Mrs. Edwards who looked after and never neglected the children, they were snatched away by an Ordering Council. I wish to bring under your Excellency's consideration the matter. I was decoyed to marry for the sake of the three grand - daughters, to keep them, and for them to be snatched away by an Ordering Council. God is no respector of persons. We are in His sight equal to all His subjects. Before the white people came to Australia. God gave us children to bring and train up for His service in our own disposition. Our disposition is instilled in our children and I don't consider it fair the white people should deprive us of our children to bring them up in their disposition. It can never be done.

I am, Yr. obedient Servant ,

(SGD.) Frederick Carmichael- Helen Baldwin

“I was born on Cape Barren Island off the North East Coast of Tasmania, but my stay on the island was not to be very long. The reason being that my Mother died when I was 5 days old, and to this day I do not know who my father was. As a result, along with my sister and brother we were left in the care of my Grandmother. At the age of 2 months the Police and Welfare officers came to the Island and took me away along with my brother and sister, there I was made a ward of the State and institutionalized. I was to spend the time from 2 months to 21 years of age in this Institution. I will always believe that I was taken under the Assimilation policy and also denied my Aboriginality.”

- Eddie Thomas

1938

Australian Aborigines Conference is held in Sydney. Meeting on January 26, the 150th Anniversary of NSW, Aborigines mark the first ‘Day of Mourning'.

1948

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights is adopted by the newly-formed United Nations, and supported by Australia.

1949

The Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide is ratified by Australia. It comes into force in 1951.

1967

A national Referendum is held to amend the Constitution. Australians confer power on the Commonwealth to make laws for Aboriginal people. Aborigines are included in the census for the first time.

1969

By 1969, all states had repealed the legislation allowing for the removal of Aboriginal children under the policy of ‘protection'. In the following years, Aboriginal and Islander Child Care Agencies (“AICCAs”) are set up to contest removal applications and provide alternatives to the removal of Indigenous children from their families.

1975

The Commonwealth Parliament passes the Racial Discrimination Act 1975.

1976

The Aboriginal Land Rights Act (NT) is passed by the Commonwealth Parliament. It provides for recognition of Aboriginal land ownership, granting land rights to 11,000 Aboriginal people and enabling other Aboriginal people to lodge a claim for recognition of traditional ownership of their lands.

1980

Link-Up (NSW) Aboriginal Corporation is established. It is followed by Link-Up (Brisbane) in 1984, Link-Up (Darwin) in 1989, Link-Up (Tas) in 1991, Link-Up (Vic) in 1992, Link-Up (SA) in 1999, Link-Up (Alice Springs) in 2000, and Link-Up (WA- seven sites) in 2001. Link-Up provides family tracing, reunion and support for forcibly removed children and their families.

1981

Secretariat of the National Aboriginal and Islander Child Care (SNAICC) is established. SNAICC represents the interests on a national level of Australia's 100 or so Indigenous community-controlled children's service organisations.

1983

The Aboriginal Child Placement Principle, developed principally due to the efforts of Aboriginal and Islander Child Care Agencies (“AICCAs”) during the 1970s, is incorporated in NT welfare legislation to ensure that Indigenous children are placed with Indigenous families when adoption or fostering is necessary. This is followed in New South Wales (1987), Victoria (1989), South Australia (1993), Queensland and the Australian Capital Territory (1999), Tasmania (2000) and Western Australia (2006).

1987

1987 Northern Territory elections are held and for the first time voting is compulsory for Aboriginal people.

The Bicentennial of British Settlement in Australia takes place. Thousands of Indigenous people and supporters march through the streets of Sydney to celebrate cultural and physical survival.

Painting: ‘Genocide', Lawry Love, 2001

Photograph: Alfred Coolwell (2nd from left), with his family on the day he first met them at Mugrave Park in 1988. Photo courtesy of Emily Bullock.

My name was Mark Saunders until I met my family and found my real name is Alfred Coolwell. I had been searching for my family since I was a young adult and had no luck.

My Foster family, I now know, lied to me a lot. They said I was from WA - not from just down the road from Ipswich at Beaudesert, that I was adopted, not fostered - my family didn't give me up. They said I left on the railway line, not stolen from my hospital bed where I was being treated for pneumonia.

To Whom It May Concern,

My name is Lena Yarry and I would like to write a few words relating to how I feel about being taken from my parents and the effects it had on me.

I am the oldest of seven children, Grace (dec), Leila (dec), Richard, Margaret, Alfred and Victor. Dad had another son, Cyril Richard Gomes by another woman from Coraki, NSW her name was Daphne.

When I first my my brother Alf and sister Marg was one day we were travelling to Ipswich to visit my Aunty Grace (Dad's sister) and Mum spotted them going to the butcher shop/ She told the cabbie to stop while I ran inside to tell them who I was and that mum was in the cab. Margaret didn't want a bar of it but Alf sneaked a phone number to me. I was so happy and Mum and I was overcome with emotion we were crying and telling our cousins about it. It really hurts me because I know Mum and Dad were trying to find them and the Native Affairs (at that time) would never reveal their whereabouts.

This photo was taken the day I met my family. I travelled up to Brisbane from Sydney to join the protest in 1988 at the opening of the Expo Exhibition. I lead the march playing the digeridoo into Musgrave Park. There, my sister Gracie recognised me (because I looked so much like my brother) and tapped me on the shoulder and said 'stay there, I am getting your family'. I felt overwhelmed, excited and tearful. I was introduced to lots of relatives, learnt about my parents, my early life and the history of my mob.

To this day I believe my Mum and Dad died of a broken heart. I love my brothers and sister. Meeting Alf was the best. he would make you feel at ease and so funny. Gee, just reminds me of me. I love his outgoing personality. Grace was just so glad that she met our brothers and sister before she passed on.

To find my family was a burden lifted off my shoulders. It gives me great sorrow my Mum and Dad never got to find my sister or me and I never met them. My older sister told me mum and dad never gave up looking for their two stolen children. They passed on not knowing us.

I thank God I met them all.

Love, Lena.

PS. The Government think they know what they're doing but they ruined my family and our lives.

Mission Breed

I grew up on an old Bre Mission

You might know the name,

It wasn't Dodge or Barwon Four

This place made me shame

It was here the welfare man

Kept me from my mother

He said in court “We're taking you

To put you with your brothers”

“You dirty low down good for nothing”

The mission man would say,

“You dirty low thing, no hoper”

His words never fade away

Snatched from friends and family

From Bourke they took me far

Away from all I knew and loved

To a kids home called Bethcar

One hundred kays northeast of Bourke

‘Bout seven miles out of Bre

Were thirty odd little Koori kids

They all looked just like me

Moonie, Monkey, Moothie, Rabbit,

Crusty Nuts, Friggity,

Dog, Cat, Big Ears, Bandicoot,

Mouse, Pointy Bum, Sadie,

Dora, Big Lips, Doody Towel,

Names that come to mind

I can't remember all of them

Memories fade with time

This little mob of mission breeds

Affectionately known

Became the only family

That I could call my own

We all grew up eventually

And some got into strife

Some stayed in Bre, some moved away

To find a better life

One thing for sure I rniss you all

dream of going back

‘tis seventeen years since last drove

That old familiar track

The day'll come when I'll arrive

Cruise on into town

I'll park down near the old fish traps

Have a look around

Then head toward the Barwon Bridge

Drive a mile or two

Turn right off the bitumen

Follow it right through

So until then I'll quietly wait

Until I can head out

To satisfy this ancient urge

The one called walkabout

We'll laugh, we'll cry, well drink some grog

Then we'll reminisce

About the life that we once lived

Growing up out on the mish.

David Nolan, Possum Wiradjuri.

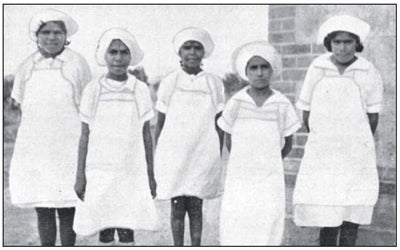

Photograph: Cherbourg State School, 1959.

Photograph reproduced courtesy of the State Library of Queensland and the community of Cherbourg.

Right-left: Vincent Serico, Adrian Jones, Jennifer Combo, Sheila Chermside, Pansy Colonel.

Boys on left: Robin O'Chin (handing our fruit), John Stanely, Glen Brown (standing near post)

1991

The Council for Aboriginal Reconciliation is set up, funded by the Commonwealth Government. Parliament noted that there had not been a formal process of reconciliation to date, “and that it was most desirable that there be such a reconciliation by 2001.”

The Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody presents its report to the Commonwealth Government. It finds that of the 99 deaths it investigated, 43 were of people who were separated from their families as children.

Jap

Am I the only one who remembers Jap

Who knew ‘Jenny' was her real name

The only one who remembers

How Jenny, at 18, died

Alone

Her lithe and beautiful body

Broken

And bleeding on the concrete floor

Of a lonely convict cell

Her bold, defiant laughter snatched

Forever from this world

With the snapping

Crack!

Of a police issue boot

On the back of her neck

I wonder if the cop remembers

The feel of her young body

Crushed

Despoiled

And lifeless beneath his heel

Has he slept well

These past thirty years

With his conscience

And his memory

Of a dark-skinned girl

With a long proud neck

And glowing dark eyes

Does he remember Jap

I do

– Vickie Roach

“Jenny ‘Jap', was 18 years old when she died in police custody. Jap and I became close friends when we were about 11 years old in a juvenile detention centre together. We were later reunited aged 17 in women's prison. Jap's death a year later was one of the still mounting tide of Aboriginal deaths in custody.” – Vickie Roach

1992

The High Court of Australia hands down its landmark decision in Mabo v Queensland No.2. It decides that native title exists over particular kinds of lands – unalienated Crown Lands, national parks and reserves - and that Australia was never terra nullius or empty land.

“On this 15th Anniversary of the High Court Decision in the Mabo case, we should indeed celebrate the hard work and achievements of Eddie Mabo and the other Meriam applicants. But at the same time, let us not pretend that the decision by the High Court recognised our land rights as we understand them, as we understand our responsibilities for country and connections with each other. We know that the High Court attempted to accommodate Indigenous law and custom within the colonial common law, but it was only able to understand our law and custom from within the framework of Eurocentric colonial legal and political systems.“

– Mick Dodson, Native Title Conference, 'Tides of Native Title', Cairns 7 June 2007

1993

International Year of Indigenous People. The United Nations declares the ‘International Year for the World's Indigenous People'. Subsequently, 1994- 2003 is declared the first ‘International Decade for the World's Indigenous People'.

The Commonwealth Government passes the Native Title Act 1993. This law allows Indigenous people to make land claims under certain situations. Claims cannot be made on freehold land (privately-owned land).

The position of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner is established within the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission (HREOC). The Commissioner's role is to monitor and report to the Commonwealth Parliament on the human rights of Indigenous Australians.

1994

The Going Home Conference in Darwin brings together over 600 Aboriginal people removed as children to discuss common goals of access to archives, compensation, rights to land and social justice.

1995

The National Inquiry into the Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from Their Families is established by the Commonwealth Government in response to efforts made by key Indigenous agencies and communities.

1996

The High Court hands down its decision in the Wik case concerning land which is, or has been, subject to pastoral leases.

Photograph: 'Sunset Story' by Heide Smith

1997

HREOC presents Bringing them home, its report on the findings of the National Inquiry into the Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from Their Families, to the Commonwealth Government. The parliaments and governments of Victoria, Tasmania, ACT, New South Wales, South Australia and Western Australia all issue statements recognising and publicly apologising to the ‘Stolen Generations'.

“In my life, I have seen my people face hostility and rejection and cruelty on more occasions than I would care to recall.

But nothing could have prepared me for the days I spent with my co-Commissioners listening as people spoke the truth of their lives for the first time.

Of being taken away from their mothers at three weeks of age.

Of mothers waiting a lifetime to see their babies' faces again.

They came before this Inquiry, and they told us of being sent to institutions ‘for their own good'.

Institutions without the loving arms of aunties and grandma's. But rather cat-o-nine tails and porridge with weevils and frightening adults who came into your room at night.

They recalled being told that their parents had given them away because they did not love them. And they told me what it was like to be taught to hate Aborigines and then turn that hate against your own history, your own mother and yourself...

This nation is proud of its rule of law.

Proud of its sense of justice and a fair go.

One of those laws is that if you steal something and you are caught, you have to give it back.

This nation has stolen.

From parents and families and communities it has stolen children.

From children is has stolen love, and family; language and culture; land and identity.

It committed a grievous crime.

It is time to pay for that crime.”

– the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner Mick Dodson, launch speech of the Bringing them home report, 1997

1997

Kruger & Ors v The Commonwealth (1997)

Alec Kruger and others lose their court case against the Commonwealth when the High Court finds that the Northern Territory Ordinance under which Aboriginal children families were removed was constitutionally valid. This case also discussed whether the policies of forcible removal could be considered genocide. The Court held that while the Ordinance did allow children to be forcibly removed, the intent of the Ordinance was not to ‘destroy...their racial group', the definition of genocide in the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (the Genocide Convention) which Australia has signed.

Painting: 'The Punishment' by Kunyi McInerney, 1994.

1998

HREOC releases the Social Justice Report 1998, which includes a summary of responses from the churches, and non-Indigenous communities to the Inquiry's recommendations plus an Implementation Progress Report.

The Commonwealth Parliament amends the Native Title Act. This restricts the ways in which native title can be claimed.

The National Archives Australia - Bringing them home indexing project is launched. The project is focussed on the identification and preservation of Commonwealth records related to Indigenous people and communities.

1999

Federal Parliament passes a motion of ‘deep and sincere regret over the removal of Aboriginal children from their parents'.

Mandatory sentencing in Western Australia and the Northern Territory becomes a national issue. Many call for these laws to be overturned because they have greater impact on Indigenous children than on non-Indigenous children.

2000

The People's Walk for Reconciliation on 28 May occurs in state and territory capitals throughout Australia. The Council for Aboriginal Reconciliation presents the Prime Minster with its declaration and four strategies to achieve reconciliation at the Corroboree 2000 Ceremony held at the Sydney Opera House.

Australia appears before the United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination. The Committee expresses concern about the Commonwealth Government's decision not to provide a national apology or to consider monetary compensation for those forcibly removed from their families as the Bringing them home report recommended.

An inquiry into the federal government's implementation of the recommendations in the Bringing them home report is undertaken by the Senate Legal and Constitutional References Committee. The Senate Committee tables its report Healing: A Legacy of Generations in November 2000 and makes ten recommendations. These concentrate on the need for ongoing reporting and monitoring of responses to the Bringing them home report and the establishment of a reparations tribunal.

The Australian Government's submission to the inquiry is presented by Senator Herron and includes the propositions that ‘there never was a generation of stolen children' and ‘the proportion of separated Aboriginal children was no more than 10 per cent'.

Final report of the Council for Aboriginal Reconciliation is presented to the Prime Minister and the Commonwealth Parliament. One of its six recommendations is that the Parliament enact legislation to address a range of unresolved issues, including the effective implementation of the Bringing them home report recommendations.

The case of Williams v The Minister, Aboriginal Land Rights Act 1983 [2001] fails.

Joy Williams loses her appeal in the New South Wales Supreme Court of Appeal alleging the NSW Government breached its duty of care by removing her from her mother soon after birth. Joy had sought compensation for the harm and mental illness she suffered as a result of removal.

The case of Cubillo and Gunner v Commonwealth (2000) in the Federal Court of Australia fails. Lorna Cubillo was removed from her family in Tennant Creek and placed in the Retta Dixon home in Darwin in 1947. Peter Gunner was removed in 1956 and placed in the St Mary's Hostel in Alice Springs. Both claimed they were seriously assaulted during their time in these institutions. Their claims failed for several reasons including a lack of evidence. Between 25 and 35 years had passed between their institutionalisation and the court case. Many records had been lost or destroyed; many of the people involved were dead; and the laws at the time of their removal allowed officials to remove children for reasons other than their own welfare.

“I jumped when I heard a screw call my name and looked up to see him beckon me with his fat finger. I dropped my broom and walked over to where he was standing on the corner of the isolation block. Well, he grabbed hold of me and shoved me inside. I can remember him starting to hit me, but can`t remember what he was saying. Then he grabbed me by the back of the neck and slammed my head into the corner of the brick wall. I wondered if he was going to keep beating me till I was dead. I remember later, sporting the bruises, swelling and abrasions, I complained to Mrs S. that I was going to dob to someone about his treatment of me. Her response was, `we`ll just say you fell over`.“

- Jeannie Hayes

2001

The Northern Territory Government repeals its mandatory sentencing laws. The same year, the Northern Territory Government presents a parliamentary motion of apology to people who where removed from their families.

The Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission and the Public Interest Advocacy Centre (PIAC) hold the Moving Forward Conference. The conference aims to explore ways of providing reparations to Indigenous people forcibly removed from their families.

“As a nation we now find ourselves in a position where we can no longer forget or ignore the truth of our past. The author Milan Kundera has noted that ‘forgetting... is absolute injustice and absolute solace at the same time'. Such ‘absolute solace', or ‘ignorance is bliss', is no longer an option for Australian society. Bringing them home has forced us to challenge some of the myths of settlement and colonisation - myths which one academic has described as having previously operated in Australia as ‘a self-constructing form of repression'.

It is now just over four years since the release of Bringing them home. It is uncontroversial to note that there is now broad community acknowledgement of the history of those forcibly removed. We cannot under-estimate how important this recognition is. However, it is but the first step in a process of healing and of addressing the consequences of this history...

This devastation inflicted upon Indigenous communities by forcible removal policies cannot reasonably be described as a distraction, or as being of little relevance to the day to day lives of its victims. Responding to forcible removals is also clearly about what the Minister describes as ‘the often forgotten needs' such as the ability of people to take control of their own lives...

Our national government owes us more than practicality in responding to a human tragedy of the scale inflicted upon the Aboriginal peoples of this nation. After four years of inaction, it is time to move forward the debate on forcible removal policies and focus on the real issues, by developing mechanisms for reparations and for healing.”

- the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner, Dr William Jonas,

Speech at Moving Forward: Achieving Reparations for the Stolen Generations, Sydney, 2001

2002

The Social Justice Report 2001 and Native Title Report 2001 are tabled in the Australian Parliament. Both reports express serious concerns about the nation's progress in improving the human rights of Indigenous.

The PIAC releases Restoring Identity - the follow up report to the Moving Forward Conference. The report presents a proposal for a reparations tribunal.

The National Library of Australia Oral History Project is published, Many Voices: Reflections on Experience of Indigenous Child Separation.

Valerie Linow is awarded compensation by the NSW Victims Compensation Tribunal. This marks the first time a member of the Stolen Generations is compensated for the harm suffered while under the care of the state. She suffered harm as a result of sexual assaults which occurred while she was a 14 year old domestic worker on a rural property where she was placed by the Aborigines Welfare Board.

2003

The Ministerial Council for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Affairs (MCATSIA) commissions and releases an independent evaluation of government and non-government responses to the Bringing them home report. This gives effect to one of the recommendations of the 2001 Senate Inquiry Report, Healing: a Legacy of Generations.

The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner publicly criticises the failure of governments to provide reparations for members of the Stolen Generation, a national apology, or the appropriate mechanisms for individuals that were forcibly removed to reconnect with their culture.

The Victorian Stolen Generations Taskforce delivers its report to the State Government. The Victorian State Government commissioned the report in response to the Bringing them home report, in order to address the hurt and suffering caused by the forcible removal of Indigenous children from their families.

2004

The Commonwealth Government unveils a memorial to the ‘Stolen Generations' at Reconciliation Place in Canberra.

461 ‘Sorry Books' recording the thoughts of Australians on the unfolding history of the Stolen Generations are inscribed on the Australian Memory of the World Register, part of UNESCO's program to protect and promote documentary material with significant international historical value.

2005

The organisation ‘Stolen Generations Victoria' is set up as a result of the 2003 report of the Stolen Generations Taskforce. Its purpose is to establish a range of support and referral services that will assist Stolen Generation members to reconnect with their family, community, culture and land.

The National Sorry Day Committee announces that in 2005, Sorry Day will be a ‘National Day of Healing for All Australians' in an attempt to better engage the non-Indigenous Australian community with the plight of the ‘Stolen Generations'.

The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (ATSIC) is abolished by the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission Amendment Act 2005 (Cth).

The first official Sorry Day ceremony outside Australia is hosted in Lincoln Fields, London, on 25 May 2005.

The Western Australian Child Health Survey is released. The report states that 12.3% of the carers of Indigenous children aged 0-17 in Western Australia were forcibly removed from their families. Compared with other Indigenous children, the children of members of the Stolen Generations are twice as likely to have emotional and behavioural problems, to be at high risk for hyperactivity, emotional and conduct disorders, and twice as likely to abuse alcohol and drugs.

The United Nations Commission on Human Rights passes Resolution 2005 / 35 that adopts the Van Boven / Bassiouni Principles. These principles declare a right to a remedy and reparations for victims of gross violations of international human rights law and serious violations of international humanitarian law.

Painting: 'Culture Shock' by Lawry Love, 2001.

2006

Bennell v State of Western Australia [2006] is handed down by the Supreme court of Western Australia. Justice Wilcox decided in favour of the Noongar people, recognising their native title rights to land including the Perth metropolitan area and coastal towns such as Bunbury, Margaret River and Albany.

THE NOONGAR NATIVE TITLE CLAIM

In early October 2005, I commenced hearing evidence concerning a native title claim that had been lodged with the Federal Court by 99 named applicants, acting on behalf of a group of people whom they described as “the Noongar People”.

The claim related to an area of land in the southern part of Western Australia. The northernmost point of the claim area, on the Indian Ocean coast, was just north of Jurien Bay, about two-thirds of the way from Perth to Geraldton. The northern boundary of the claim area then extended easterly, north of Moora, before bearing south-easterly to meet the Southern Ocean slightly west of Esperance. This is a vast area of land, taking in the Perth metropolitan area as well as major coastal towns, such as Bunbury, Mandurah, Margaret River and Albany, and many towns in the wheat-belt.

It was apparent that much of the land in the claim area would be freehold or held under a lease that had extinguished any native title. If the claimants were able to demonstrate the necessary connection with the claim area, there would need to be detailed discussions, or a further hearing, about the particular parcels of land that were still subject to native title. However, all parties agreed this should be left for another day; the immediate task was to determine whether there was any subsisting native title at all.

In order to make good a native title claim, it is necessary for the claimants to establish:

(1) the identity of the indigenous group under whose laws and customs land rights were regulated at the date of European settlement; in this case, 1829;

(2) that this group has since continued to exist, and continued to observe its laws and customs relating to land, subject only to any variations that have been forced upon it by later circumstances including, particularly, white settlement; and

(3) that the instant claim is made on behalf of the members of that group or an identifiable part of it.

The applicants' case was that, in 1829, a society of people, now known as “the Noongar People,” occupied the whole of the claim area; they had a complex of laws and customs, relatively homogenous throughout the whole area, that governed land rights. Under these laws and customs, each person had primary rights over the relatively small area of land upon which he or she usually resided, in an extended-family unit, and for which the unit's members had management responsibilities. They “spoke” for that country. People also had secondary rights over a larger area of land, the primary rights to which were held by others. People were free to access their secondary country, but were not entitled to “speak” for it. If people wished to visit country to which they did not have either primary or secondary rights, they needed the permission of the right holders.

The applicants' case was that the Noongar People continued to exist as a society, although in a changed form, and to apply, as between themselves, the traditional landholding rules.

The Western Australian and Commonwealth Governments both contested the claim. They said the relevant group, at date of settlement, was not constituted by all the people who resided in the claim area in 1829 but that land in this area was then held under the laws and customs of much smaller, “clan” groups; so any native title claim had to be brought in their name, and on their behalf. The two governments disputed that there was ever an Aboriginal society that extended over the whole claim area and said, alternatively, that, if there ever had been, it no longer existed.

I heard evidence over 20 days. Written and oral evidence was given by expert witnesses, (two historians and two anthropologists, one of each being called to give evidence by counsel for the applicants and the other by counsel for the State, and a linguist called by counsel for the applicants) and by 30 Aboriginal people. The Aboriginal evidence was given over 11 days, all “on country”, under canvass in a makeshift courtroom that was moved from one location to another within the claim area.

Counsel also tendered many documents. These included the writings of several Europeans who were either stationed, during the period 1826-1829, at the garrison at King George's Sound (modern Albany) that preceded the Swan River settlement or were early settlers in the Perth area. Each of these writers attained some knowledge of the local Aborigines, and their laws and customs, and, in some cases, became fluent in their language. These writings, combined with the linguist's expert evidence, established that, in 1829, there was a common language throughout the claim area, albeit with dialectic differences. This finding, supplemented by evidence of the degree of contact between the Aboriginal people in different parts of the claim area and the similarity of their laws and customs, led me to conclude that, in 1829, there was a single society that occupied the whole of the claim area and whose laws and customs regulated land rights.

The more difficult problem was the effect of European settlement on this society. The evidence about this was graphic.

The first European settlement, as distinct from the garrison, was in the fertile Swan Valley. This area had previously been home to many Aboriginal people, no doubt because it sustained abundant food sources. However, the early white settlers fenced off their land grants and drove out the wildlife. The Aborigines, deprived of a principal food source, responded by taking the settlers' stock for food. This led to reprisals. Many Aborigines were shot for stealing. Within a few years, the Swan Valley lost most of its Indigenous population. As settlement expanded, so did the area from which Aborigines were excluded, at least in the sense of being able to maintain their traditional lifestyle. The Aboriginal people either moved further out, into unsettled areas that were the “country' of other Noongar people, according to their traditional laws, or took employment, as stockmen or domestic servants, with the European settlers; in the process, family members were often separated. People from different areas were often congregated together in missions or on Aboriginal reserves. The effect was to weaken peoples' links with their country.

Most of the Aboriginal witnesses gave detailed evidence about their descent, usually extending back four or five generations. Every one of these witnesses mentioned at least one white male ancestor. It appears that, when the British Government decided to transport convicts to Western Australia, and in contrast to its policy in respect of earlier transportation to the eastern colonies, it paid little attention to the need to maintain a convict gender balance. The result was a substantial excess, in Western Australia, of males over females. Predictably, many white males formed relationships with black women. Although it seems many of these relationships were loving, long-term relationships, they had two far-reaching effects.

First, the traditional rule, throughout most of the claim area, was that children took their rights to country through their fathers. If the father was white, he had no country to pass on. But connection to country is fundamental to Aboriginal life and culture. So, rather than have children lose any connection to country, the Noongar people accepted inheritance through the mother. This modification of the traditional rule was relied on by the two governments, in the Noongar case, in arguing that the present body of rules was not the body of laws and customs operative in 1829.

Second, over a period of about 50 years, there was an official policy in Western Australia (in common with most other parts of Australia) of removing “mixed blood” children from their families. Because of the high proportion of Noongar children who had at least one white male ancestor, almost all of them were targets for removal. Many were in fact removed, most notoriously to the Moore River camp that was depicted in the film ‘Rabbit-proof Fence'. Many of the witnesses before me had themselves been removed from their families or told of parents or siblings who had been removed. Sometimes removed children were eventually reunited with their families; often they were not. In terms of community cohesiveness, the consequences of the removal policy were profound.

After completion of the evidence, counsel prepared and submitted to me written submissions dealing with every aspect of the case. I eventually reached the conclusion, contrary to my original expectation, that the applicants had proved the survival of the Noongar society from 1829 until the present time. The basis of my conclusion was compelling evidence about five matters: the continuing use of the Noongar language by many people throughout the claim area; the adherence by all the witnesses to a complex of spiritual beliefs that accorded broadly with the beliefs noted by the early European writers and were widespread in the claim area; the maintenance of traditional hunting practices, even where this was not necessary for food-gathering purposes; the continuing coming-together of people for festivals, funerals etc; and, most importantly, the continued adherence, by many people, to the traditional rule about seeking permission to visit someone else's country.

I handed down reasons for judgment to a packed court, in Perth, in September 2006. The reasons were lengthy, so I merely made a statement about the history of the case, the main issues and the result. When it became clear to the audience that I accepted the claim that the Noongar society, and Noongar culture, had survived, there was an audible, collective intake of breath and widespread emotion.

The evening television news services featured celebrations involving many hundreds of people. A few days later, after I had returned to Sydney, my Associate took a telephone call from a woman who identified herself as Noongar. She said she practised as a psychologist and had many Noongar patients. She asked my Associate to tell me my finding had given the Noongar people a psychological lift like none she had seen before. The message tended to conform a feeling I had gradually developed over my long exposure to native title litigation: the most important result of success in a native title case is not in relation to permissible uses of the subject land, but the communal recognition and affirmation it provides.

My finding is the subject of an appeal, probably the main issue being whether the modifications to the traditional laws and customs that have occurred since 1829 — in my view, as responses to the effects of white settlement — mean that the rules now observed cannot be said to be the laws and customs in force in 1829. Whatever the final outcome of the case, it will not take from me the memory of the Noongar reaction to my decision.

- Murray Wilcox QC, former judge of the Federal Court of Australia.

Photograph: by Fabienne Balsamo

2006

The first Stolen Generations compensation scheme in Australia is set up in Tasmania by the Stolen Generations of Aboriginal Children Act 2006 (Tas).

First payout deal for stolen children

The Australian, Matthew Denholm,

18 October, 2006

The national debate on the "stolen generations" will be reignited today by the unveiling of the nation's first compensation package for Aborigines taken from their parents under assimilation policies.

Tasmania will today announce a government apology and a $4 million compensation scheme for members of the stolen generations. The Australian understands the scheme will involve the appointment of an independent assessor, who will judge individual cases against set criteria.

The assessor will consider individuals' testimonies and examine government records to test claims of wrongful removal by welfare agencies, mostly from the 1930s to the 1950s.

A compensation funding pool - to be capped at about $4million - will then be distributed among those found to have genuine cases. While the number of potential applicants is unknown, the Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre has already identified 40 individuals with "solid claims" for compensation. The scheme - hailed by Aboriginal leaders yesterday as a model for other states to follow - will be advertised nationally to invite applications from those who may have left the state.

Premier Paul Lennon will sell the package as lifting a key barrier to reconciliation between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal Tasmanians. Yesterday, Aboriginal leaders praised Mr Lennon's "leadership" and "courage" and expressed hope it would rekindle national debate on the issue.

It is nine years since the release of the Bringing Them Home royal commission report into indigenous children removed from their families. TAC legal adviser Michael Mansell said he hoped other states would examine and adopt the model and that the Prime Minister would reconsider his opposition to an apology for the stolen generations. "This is a very groundbreaking decision and not just the other states but John Howard also should ... take a very close look," he said.

Official reasons for the removal of Aboriginal children to institutions or foster homes included maternal "neglect" or "waywardness". However, many Aborigines believe these were often groundless excuses to suit a policy of assimilating black children into white foster families wherever possible.

Some claimants told The Australian the scheme would allow them to "begin to forgive". Eddie Thomas, 70, believed to be the oldest surviving member of the stolen generations in Tasmania, was taken from his grandmother when he was six months old. He and his brother and sister had been placed in her care when his mother died after his birth on Cape Barren Island, northeast Tasmania, in 1936.

He believed his grandmother was duped into signing a consent form. "She couldn't read or write, so she couldn't have been in agreement," he said. His life with white foster families on mainland Tasmania was unhappy and his grandmother was prevented from visiting the children, he said.

"There used to be this old lady come to the gate and our foster mother would say, `That's just a silly old black woman', and take us inside," he said. "It wasn't until I was old enough to go to work that I met up with an uncle who told me that was my grandmother. She wanted to talk to us, to cuddle us, but she wasn't allowed. She died of a broken heart.

"I've felt for a large part of my life so much anger, but this (an apology and compensation) will allow me to move forward and to forgive those people."

Heather Brown, 63, broke down as she recalled the day she and six other children were taken from her family home.

"Those people just came through our home and got me -- I ran, there were children running everywhere," she said. "It happened all at once. I was dazed. I didn't talk for months afterwards."

She still does not know why she was taken from her parents at Wiltshire Junction, northwest Tasmania, or why she was not allowed to see them or her siblings while she grew up in a succession of foster families. "I'll never forget," she said.

Annette Peardon, 57, said she and two siblings were taken from their mother on Flinders Island, because of maternal "neglect". She disputes this, remembering a clean home with sufficient food.

The childhood that followed was marked by "physical, emotional and sexual" abuse at institutions and foster homes, she said. While she found her mother after turning 21, her sister and brother were never reunited with her.

"It broke her spirit -- she had three children taken away and only one went back," Ms Peardon said.

Many of those affected have since died, but the TAC has identified 27 individuals it believes have an "extremely strong" case for compensation.

The scheme fulfils a commitment first made by Mr Lennon in The Australian two years ago and repeated at the March state election this year.Article reprinted courtesy of News Limited.

Photograph: Eddie Thomas, Premier Paul Lennon and Annette Peardon after the successful passage of Tasmanian compensation bill.

Courtesy of Eddie Thomas.

”After all these years of struggle a breakthrough finally came. Our long time Tasmanian Aboriginal lawyer and Activist Michael Mansell who has worked so very hard for us, phoned up and told me that Annette Peardon and myself were to attend a function for the history-making handing down of the Landmark Draft Bill for the Stolen Generation to make an Apology and to compensate them... this happened on October 18th, 2006. This was to be the beginning of history being made... eventually a date had been set to attend Parliament, it was a full sitting of the Lower House.

This was history making, never before in Tasmania had members of the public been invited to the floor of the Chamber to speak while Parliament was in progress.

While we were waiting to be taken into Parliament by the Sheriff... I felt very nervous this was a very important occasion. But the time came to enter the House, I was to speak first, I was introduced to the Speaker, who in turn introduced me to the Members, I was now at the lectern and microphone and I felt so proud and for some reason I was no longer nervous. I looked around addressed the Speaker, the Leaders of each political party, after doing this I was on my way... the words spilled from my mouth.

How being stolen from my family under the Assimilation act, the denial of my Aboriginality, the loss of my family, community and culture.

On top of this I spent twenty years in a cruel institution, being a slave to others. By the time I had made my address (I really spoke for all members of the Stolen Generation) I don't think there was a dry eye in the House, both men and women, I know they felt very much for us. History was made again when the Compensation Package was passed through the House unanimously.

But still there were a lot of butterflies, because we now had to get it through the Upper house and everybody knew it was going to be touch and go. We were present in this sitting... [and it was] a nervous wait.

This was on the 28th November 2006 and there was quite a lot of discussion... but after the third reading the Compensation Package was passed. What a joyful and emotional time this was as we came out of Parliament House, news travels fast because there were cameras everywhere and a large crowd of our people to cheer us. I was fortunate enough to be one of the first to congratulate our Premier Paul Lennon, because I knew what a huge effort he had put in for us.

I must say that it has been a long road to this victory, but it has helped a lot of people to come to terms with life, it has given them justice and something to build a new life around. Money cannot erase all the sadness, but it will help us to now enjoy our lives and to help our families.

– Eddie Thomas

Photograph: Sewing Class, Mapoon Mission, 1960.

Photograph reproduced courtesy of the State Library of Queensland and the community of Old Mapoon.

2007

2007 The 10th anniversary of the Bringing them home report is commemorated in May.

“The 10th anniversary [of the Bringing them home report] is a bittersweet one. For many Indigenous people, they have benefited greatly from the responses that governments have provided to the report's findings over the past decade, and also from the public groundswell of compassion and support that has resulted.

Many people have been reunited with their families. Others have been able to trace and learn details about what happened to their families. And the vital services that had previously been provided by organisations such as Link-Ups - without much funding and without recognition – have been able to obtain ongoing funding so that they can better service communities of Indigenous peoples who were removed.

These are important outcomes and ones that we must celebrate as we look back on ten years since the report was released.

But it is a bittersweet anniversary because others have not benefited similarly from the responses to the report.

There were two aspects to the awareness created by the report – it had an effect of validating the experiences that many people had lived. But it also raised the ghosts of those experiences – the trauma, the grief and the memories. Left unresolved, this can have the effect of re-traumatising people and creating a ‘limbo' world in which they have not been able to go home.

It is unfortunate, but the hostility towards the report's findings by government has contributed to this re-traumatisation. That is why an ongoing commitment to reconciliation remains such an important need in our country today.

So as we commemorate the tenth anniversary of the report, we must also remind ourselves of the suffering that many of our brothers and sisters have continued to endure, and the challenges that remain unmet for those who were forcibly removed, for their children and their children's children.”

- the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner, Tom Calma, speech at a Parliament House, Canberra, May 2007.

2007

Trevorrow v State of South Australia (2007)

Reflections on the case, Joanna Richardson, solicitor for the plaintiff.

On 1 August 2007, His Honour Justice Gray handed down his decision in the matter of Trevorrow v State of South Australia. It was the moment that Bruce Trevorrow and his legal team had been working towards for 13 years. Despite being unwell, Bruce had travelled from Bairnsdale on the east coast of Victoria, to Adelaide to hear the decision. I had arranged to meet Bruce and his family beforehand. We were all very nervous. We reminded each other that whatever the outcome we had put the best case we could, and we now knew the answer to the questions that Bruce asked when we first met at Aboriginal Legal Rights Movement (ALRM) in March 1994: Why had he been removed from his family when he was little? Why did he find life so difficult?

After meeting Bruce I began to seek and obtain government documents that recorded what had happened to him. At first we were given only a small part of his personal file. These documents included a report from the local police officer to the Aborigines Protection Board which recorded that on Christmas Day 1957 Bruce had been unwell and his father had insisted that he be taken to hospital. From there he was placed with a white foster family, but at this point we had no idea why. There was a letter from Bruce's mother, Mrs Thora Karpany, to the Secretary of the Aborigines Protection Board dated 25 July 1958, asking about her son, asking how long before she could have him home, telling the Welfare Officer she had not forgotten she has a baby son. The Secretary replied on 19 August 1958, telling Mrs Karpany that as yet the doctor did not consider Bruce fit to go home. Later, I found hospital records that demonstrated that Bruce had quickly recovered from his illness and, contrary to the Secretary's letter, it seemed he was not under the care of a doctor in August 1958.

After I was granted access to the files held at State Archives, I also obtained correspondence and policy documents of the Aborigines Protection Board, the Secretary of the Board and the Aborigines Department. Included in that material were the opinions of Crown Solicitors, documents which recorded the inability of the Children's Welfare and Public Relief Board and Aborigines Protection Board to reach agreement about the treatment of Aboriginal children and frank admissions by the Secretary of the Aborigines Protection Board to his counterpart in Victoria that, without lawful authority, many children were being placed in institutions and with white foster families. He estimated that in 1958 there were approximately 300 children who had been placed in this manner.

In 1998 we issued proceedings against the State of South Australia. We argued that the State did not have the power to remove him from his family in the way they had, i.e. the State had acted unlawfully or beyond its powers; that Bruce had been falsely imprisoned and that the State knew they acted unlawfully when they removed him. We also argued that the State had owed Bruce fiduciary and common law duties of care. For example, as the Aborigines Protection Board was his “legal guardian” they were obliged to protect him and, because they knew he had been unlawfully removed from his parents, they were obliged to make sure he got independent legal advice about what had happened to him.

Also, the Board had to make sure they were very careful about removing babies, they had to make sure there was a good reason why a baby should be taken away, that the foster placement was good and healthy, and then when the child was returned to the parents, they had to make sure that was done in a safe way. We said the State had not done those things properly and had therefore breached those duties of care.

We said Bruce had suffered permanent injury and loss, including loss of culture, as a result of his removal, his placement and in the manner of his return to his family. As a result of this treatment Bruce sought declarations and damages, including exemplary and aggravated damages which are sought when the defendant has acted in complete disregard of a person's rights or in an especially malicious or fraudulent way.

The State vigorously defended the claim. It denied Bruce had been unlawfully removed and denied it was liable for the actions of the Aborigines Protection Board. It argued that, as a result of the passage of time, it would suffer prejudice if the claim were permitted to proceed.

For the next seven years the action ground through numerous preliminary stages. Background events also made our preparations very difficult. Bruce suffers from ill health, and the lengthy process took its toll on him and on his family. The passage of time made it impossible to keep together a core legal team. I was the only lawyer who remained acting throughout that time. Many people have made important contributions to the presentation of the case: Robyn Layton QC, who acted as senior counsel until the end of 2005; Gordon Barrett QC and Sydney Tilmouth QC; Andrew Collett and Nigel Wilson, junior counsel who assisted in the preparations; and Julian Burnside QC and Claire O'Connor both of whom accepted the brief only weeks before the trial began and who must have blanched when we began to inundate them with volume after volume of pleadings, materials and reports, and whose advice and skills proved critical. Then there are the researchers, some of whom started as volunteers and who worked on the case at various times: Graham Hyde, Andrew Alston, Christopher Holland, Dr Irene Watson; George Lesses, Christopher Johnston and most importantly, Andrew Nettlefold.

Other legal processes also had an effect. The Joy Williams claim in NSW was unsuccessful, and we saw the toll that action had on Mrs Williams. In the Northern Territory claims were brought against the Commonwealth on the part of Mrs Cubillo and Mr Gunner. Although those claims were unsuccessful I remember reading the judgements and realising that the facts of Bruce's case and the laws in South Australia at the time he was removed meant that those decisions did not deal a fatal blow to his claim, in fact the decisions strengthened his claim. At the same time, important cases about the extent of the liability of statutory authorities (which broadly means the responsibility of government to the people they look after) were being decided in Australia and in the United Kingdom.

In March 2005 the claim was given trial dates in November 2005. The trial lasted for 37 days, spread between November 2005 and April 2006. In the course of the trial 173 exhibits were filed, expert evidence was heard about the plaintiff and his health, about the knowledge in the late 1950's of the harmful effects of the separation of a child from their family, and evidence was taken from, amongst others, Bruce and his family, from his foster sister and officers of the Aborigines Department.

Finally, on 1 August 2007, Justice Gray delivered his decision. He found for Bruce, he rejected the State's defence.

At the time of preparing this article we do not know if the decision will be the subject of an appeal to the Full Court of the Supreme Court of South Australia. Although the Premier, Mr Rann, has announced that the State would pay Bruce the compensation he has been awarded, the State has nevertheless reserved its right to appeal the decision.

So, at this time, what does the success of this case mean for others? It recognises that in South Australia, the State through the Aborigines Protection Board, the Children's Welfare and Public Relief Board and the Aborigines Department, engaged in a practice whereby Aboriginal children were removed from their families despite the fact that it was known there was no legal authority or power to do that. In 1958 the Secretary of the Aborigines Protection Board estimated that approximately 300 children had been dealt with in this way. It was done despite the fact that they knew such removals carried risk of harm to children. And, as was demonstrated in Bruce's case, even when there was sufficient material to demonstrate the child was not, in fact, neglected, the child was not returned to the care of his family. Instead, accurate information about the child was withheld, his parents were misinformed and their attempts to have their child returned to their care thwarted.

It also has broader implications across Australia. The decision is authority for the proposition that by the mid- 1950's it was reasonably foreseeable that the separation of infant Aboriginal children from their families and placement in long term non- Indigenous foster care created real risks for the health of those children. Officers of the State working in this area foresaw those risks, or ought to have foreseen those risks. One of the consequences of the foreseeability of this risk of harm is that the State then owed duties of care to the children in the manner of their removal, their placement and their return to family. The State can be held liable where it is demonstrated that the duties of care have been breached and the child has suffered injury and loss as a result of the breach.

What can we learn from the conduct of this case? It has confirmed what we already knew, that litigation is costly in terms of time, money and emotion. As was recommended ten years ago in the Bringing them home report, litigation should not be the method by which other Aboriginal people who have suffered from similar actions, whether by reason of their removal, placement or return to family, and there are others, should be forced to seek redress.

For a more comprehensive explanation of the case and a summary of Justice Gray's findings by Joanna Richardson, visit our website www.humanrights.gov.au/bth

" I don`t recall what I`d done exactly, but I was locked up underground in the dungeon. It was a creepy place to be and the imagination, born from the stories the girls would tell, would run rampant in my mind. Time turned over every so slowly in the dungeon... what I do remember from three weeks in segregation is that I had bruises from a bashing. I can`t remember why or who had done it, but I knew I was being kept there until those bruises faded... I was sweeping what we called the cubaway (or covered way) when a screw called me into his office. Now, that fat man started to punch and slap me about and he landed a couple of punches into my stomach. I guess he was dreaming about being a boxer and was looking for a bit of practice on someone who couldn`t, rather wouldn`t dare hit back, such as a small girl like myself. I don`t rightly remember what it was all about, but I do remember walking out of that office to a group of girls, who were standing by worried about me, with a smile on my face and told them it didn`t hurt. Well, the screw heard me and called me back to the office... I reckon it was then he shoved me down the stairs to be locked away in the dungeon. The screws loved to push me down those steep narrow dungeon steps. They wanted me to take a fall, but I don`t think I ever did."

- Jeannie Hayes

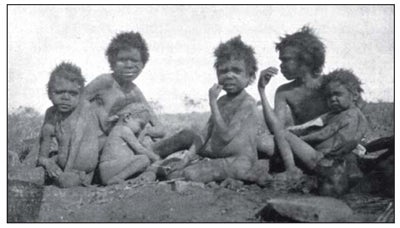

Photographs: ‘Girls living under the stone age system' and ‘Native girls living under civilised conditions', Photographs of Australian Aborigines, Australian Aborigines Friends' Association, 1936.

Photograph courtesy of Ivan Copely.

2007

Roach v AEC and Commonwealth of Australia [2007]

Vickie Lee Roach, an Aboriginal woman from Wiradjuri country in NSW, serving time in Victoria's Dame Phyllis Frost Women's prison, wins a High Court challenge. She and the Human Rights Law Resource Centre in Victoria successfully overturn legislation which banned prisoners serving a sentence of three years or less from voting at elections. The High Court held the legislation was unconstitutional.

“This year marks 10 years since the Bringing them home report. Out of the seven siblings that were taken away from my mother four of us were not return to my mother's care, after the death of my brother I was sent home but ran away after my mother started drinking again. My other brother and sister have never been returned to my mother, they are adults now and have families of their own- I was hoping that during the 10 years I would had made some contact with my siblings but this has not happened.With the help of Bondi Mayor, who has offered a space at Bondi for a Stolen Generation Memorial wall, my brothers and sister will be remembered in 2008 on 26th May, National Sorry Day. This has been my dream ever since my brother was killed. Not only will he be remembered, but for all my Aboriginal brothers and sisters who were never brought home.”

- Mary Hooker

Mary's will to survive

By Ellen McIntosh, The Penrith Press, March 13, 2007

TORN from her family at eight, abused by supposed protectors, labelled a delinquent and “borderline retarded” - it could have been easy for Mary to yield to the stereotype. But she has spent a lifetime fighting to prove the system wrong and seeking justice for herself and other members of the “stolen generation” of Aboriginal children.

Mary, 49, of Kingswood Park, has told her story publicly over the internet and for the Warsaw Museum. She also testified at the Parliament inquiry into the “stolen generation”, which adopted just one of the 54 recommendations from the Bring Them Home report - to encourage Aboriginal people affected by the forcible removal policies to tell their stories.

Mary said her Department of Community Services file stated her IQ was "borderline retarded", but at age 40 she enrolled in university. She now has childcare qualifications, nursing training and last year graduated from Bible college, qualified for the Indigenous ministry.

She has been married for 22 years and has two adult children and two grandchildren. "I didn't want to be like my brothers and sisters, using [the abuse] as an excuse and a crutch," Mary said. "I was determined to fight the system and prove that I wasn't useless."

One of Mary's most rewarding achievements will be the unveiling of a memorial at Bondi on May 26, the 10th anniversary of national Sorry Day.

It will mark the death of her younger brother Tommy and other Aboriginal children who have died in care.

Mary said Tommy died in 1975 after falling from a train during a trip home to Taree for holidays. He and four other state wards were insufficiently unsupervised, she said.

Mary was eight when she was removed from her parents and the Aboriginal reserve on which they lived near Taree. She said eight of her 10 siblings were removed during the years, separated and trained to be housekeepers and nursemaids to white people.

Mary was sent to Mittagong but ran away, classified a delinquent and sent to Parramatta Girls Home. She said unruly girls were taken to "the dungeon", blocked off tunnels leading to the neighbouring psychiatric centre.

"That's when the men would come to bash us and rape us," Mary said. "We were told not to tell anybody because nobody would believe us and that they were our parents and they could do anything they liked to us."

In 2004 Mary saw "the dungeon" again at a reunion and the memories flooded back. She said one by one, scores of other women admitted they too had been abused there. Mary said she was next sent to be a governess at Vaucluse, and then to Reiby Training School at Campbelltown after she ran away again.

Meanwhile, the abuse continued, she said. "When I was 18, I was given a letter by the department and told I was no longer a ward of the state. That was it."

Mary continues to fight to have the offenders charged by police: "They need to be accountable to me: I want to know why. "I was taken off my parents for neglect, but they did far worse – my parents never bashed or raped me." Mary said she was also suing the Department of Community Services, although a department spokeswoman said she had not served any court proceedings on the department.

She had made some claims against the department "which, on the basis of the information supplied, cannot be substantiated". While Community Services Minister Kay Patterson officially apologised to Aboriginal people in June 2005, "no information has been supplied by [Mary] that would establish that she is a member of the ‘stolen generation' or that this is the basis of any claims", the spokeswoman said.

Article reproduced courtesy of the Penrith Press

(www.penrithpress.com.au).